Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis - March, 2019

© 2019 Regents of the University of California

Moving into the 21st Century

-- Anne Foley Scheuring, Science & Service: A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, at p. 119 (1995).

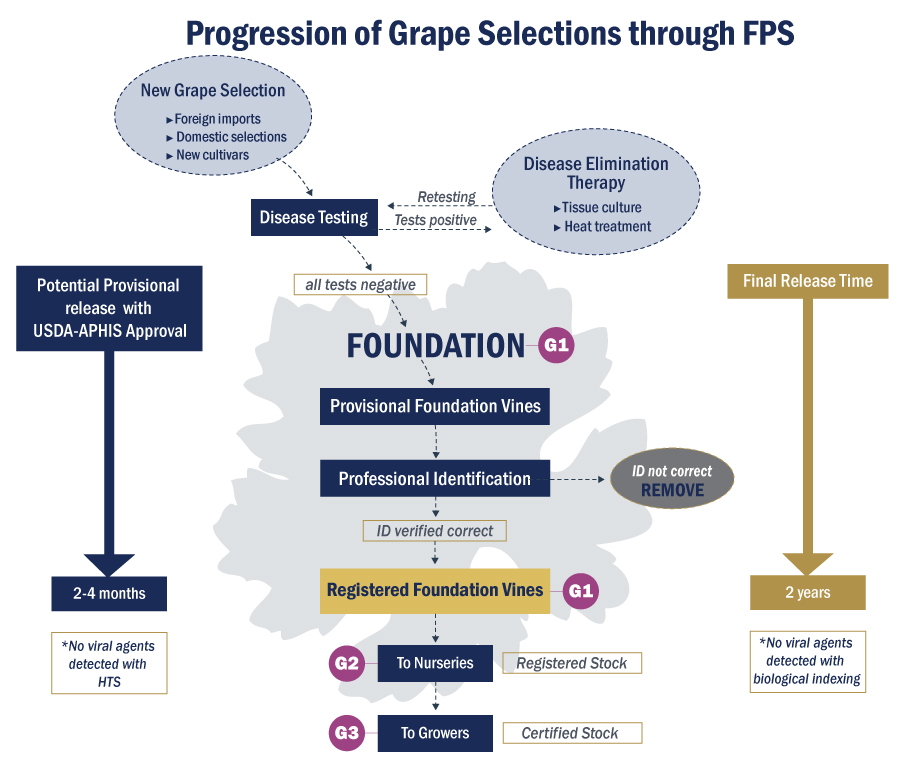

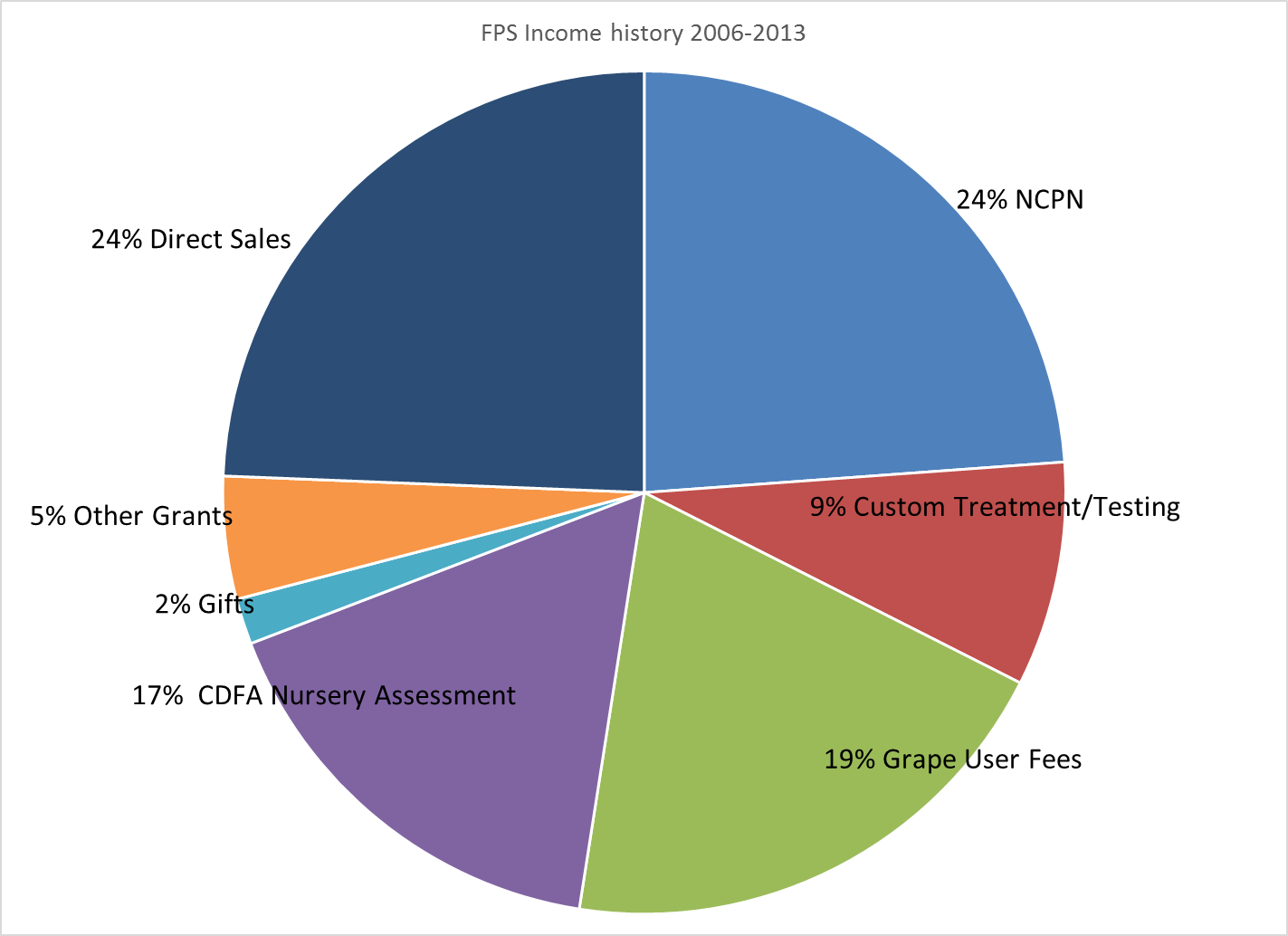

Foundation Plant Services is a clean plant center at the University of California, Davis. The primary goal of the center is to create, maintain and distribute high quality, virus tested plant material to customers. Secondary goals include information sharing and diagnosis on disease issues and development of advanced technologies for disease detection. Although the work includes applied research, FPS is mainly a service center with a focus on extension work and outreach to the industry.

Extension work at public universities has been defined as the “bridge” between the land-grant colleges and farmers in the countryside. The purpose of extension work is to bring university experiment station research directly to the people who could use it to improve their lot. 1 Anne Foley Scheuring, Science & Service: A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, at p. 146 (ANR Publications, Regents of the University of California, 1995). FPS’ largest customer group consists of grapevine nurseries, grape growers and wine makers.

Despite the nod towards the service component in the above quotation, the practical reality is that university administrators often place a greater value on teaching and research, exemplified by favoring publication over service work for academic promotions. Land grant colleges have a difficult time making a place for applied research and service work. Extension programs and service centers frequently experience funding and staffing difficulties as a result of the tension between competing needs at the public universities. The difficulty was even more challenging at the University of California in the face of budget cuts in the decades prior to 2000. For a time, it appeared that FPMS/FPS might become another casualty in that scenario. 2 Anne Foley Scheuring, Science & Service: A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, at pp. 146-155 (ANR Publications, Regents of the University of California, 1995).

FPMS/FPS faced serious challenges in the 1980’s. Although sales of the certified grapevine material mostly carried their own funding weight at FPMS, the primary concern late in the decade was the future of virus testing at the grapevine importation and quarantine program at the facility. Austin Goheen’s retirement left a void in the Davis program. The Department of Plant Pathology had withdrawn from FPMS some of the resources previously used to test and treat the imported grapevine material on the basis that the work involved time-consuming service work and not research. The center lacked the facilities and personnel to continue adequate testing and treatment work requested by its customers: the grape and wine industry. The future of the clean plant program at UC Davis was uncertain.

Fortunately, the key players in that scenario – University of California, FPMS, CDFA (California Department of Food & Agriculture), nurseries, winemakers and growers – recognized a mutual need and cooperated to develop a center that has become a national leader for healthy grapevine material. FPMS made significant strides in improving the quality of its clean plant program beginning in the late 1980’s with the addition of new scientists and the application of new testing and therapy strategies to combat serious disease threats.

Significant upgrades in disease testing technology initiated beginning in the 1980’s have transformed the quality of the foundation grapevine material available in 2019. At the same time, the distribution of a clean plant product as well as decades of education on its value have improved the quality of vineyards throughout the United States for the benefit of FPS customers and the public. Those efforts have made FPS one of the premier clean plant centers in the world.

FPMS RESTRUCTURED

The problems experienced in the 1980’s by FPMS and its umbrella unit FSPMS (Foundation Seed & Plant Materials Service) were addressed in a comprehensive fashion by the University of California. As a result of an intense and thorough evaluation process, FPMS emerged as a stand-alone service center with strong leadership. New facilities, upgraded technology and more effective disease testing and treatment strategies set the center on a positive course.

The restructuring effort was motivated in part by the problems experienced by FPMS in the 1980’s. The unexpected incidence of viruses in the foundation vineyard, inadequate FPMS nursery practices and mix ups regarding grape rootstocks caused much concern within the grape industry. 3 Letter from Cal Qualset, acting Director FSPMS, dated October 18, 1993, Foundation Plant Services collection AR-050, box 34: 6, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

After several years of meetings addressing needed improvements to the clean plant program at UC Davis, FPMS underwent an extensive evaluation by a special industry/University task force, the recommendations of which would materially affect the program in 1993. Efforts to restructure the FPMS program proceeded at the University on a parallel track with the development and construction of the new importation and quarantine facility, which was completed in 1994.

An extensive review of FPMS was undertaken as part of a review of the UC Davis umbrella unit FSPMS (Foundation Seed & Plant Materials Service). FSPMS had since 1975 become too complex technically and too large to be served by a single Director. Unique advancements in technology and industry needs differed for hundreds of seed-produced crops versus clonally reproduced crops. It appeared that effective satisfaction of future industry demands would require expansion and efficient reorganization of the programs. A review was conducted to judge the effectiveness of the FSPMS program, including services to its clientele, organizational and managerial efficiencies and fiscal condition. 4 Review of Foundation Seed and Plant Materials Service (FSPMS), A Task Force Report, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of California, Davis, December, 1992, p. iv (hereafter referred to as Task Force Report).

The FPMS portion of the review was conducted in three phases. After an internal review within the University, an external review was conducted in 1991 by a review team composed of representatives from clean plant centers similar to FPMS in Canada and the U.S. The external review received little input from the grape industry. The findings were characterized as “anecdotal” and “claims without evidentiary support”. FPMS Advisory Committee member and grape winegrower Phil Freese reported to the FPMS Grape Committee in November of 1991 that a final phase of the review had been approved by AES Dean John E. Kinsella in October 1991. The review would have substantial industry and University representation.

Dean Kinsella appointed Calvin Qualset, Robert Woolley and Phil Freese as co-Chairs of the UCD-Industry Task Force, which included members from all the University departments that interacted with FPMS, as well as representatives from industry, CDFA and USDA. 5 Minutes, FPMS Grape Subcommittee Meeting, November 5, 1991, included in FPMS 1992 Annual Report, Foundation Plant Services collection AR-050, box 29: 49, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; Task Force Report, supra, at p. 3. Qualset was at the time Chair of the UC Davis Agronomy and Range Science Department and Director of the Genetic Resources Conservation Program. Woolley, owner and general manager of Dave Wilson Nursery, represented the fruit and nut tree constituency. The Task Force completed its review in December, 1992, and published its findings in spring, 1993. Dean Kinsella accepted all of the recommendations of the report before his untimely death in 1993. 6 “Dean’s Review of Foundation Seed and Plant Materials Service Completed”, FPMS Newsletter, number 13, October 1993, page 1.

The most visible and important recommendation was that the umbrella unit FSPMS be disbanded and two independent service centers be formed, each with its own Director. One new center included Foundation Seed Program and the California Crop Improvement Association for seed-related services. The second center was Foundation Plant Materials Service (FPMS), which was then a unit with eight employees that provided a program for clonally propagated crops such as grapes, strawberries, and fruit and nut trees.

UC agreed to create a faculty-level Director’s position for FPMS, composed of 70% FTE Academic Administrator series and 30% Cooperative Extension specialist. The new Director would thereafter report directly to the Office of the Dean, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at UC Davis. 7 Task Force Report, supra, at pp. iv and 16-18. A PhD was required in a field relevant to the FPMS mission (horticulture, plant pathology or genetics). The USDA-ARS would no longer provide personnel to manage any aspects of the FPMS program.

Recruitment for the Director position for both new centers was underway by fall of 1993. Cal Qualset had served as Acting Director of the umbrella organization FSPMS since 1991 and continued to do so until the Director positions could be filled for the new centers. 8 “Dean’s Review of Foundation Seed and Plant Materials Service Completed”, FPMS Newsletter, number 13, October 1993, page 1; Minutes, FPMS Grape Advisory Board Meeting, June 15, 1993, Foundation Plant Services collection AR-050, box 23: 14, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; “FPMS Staff Changes”, FPMS Newsletter, number 11, October 1991, no. 11, p. 1.

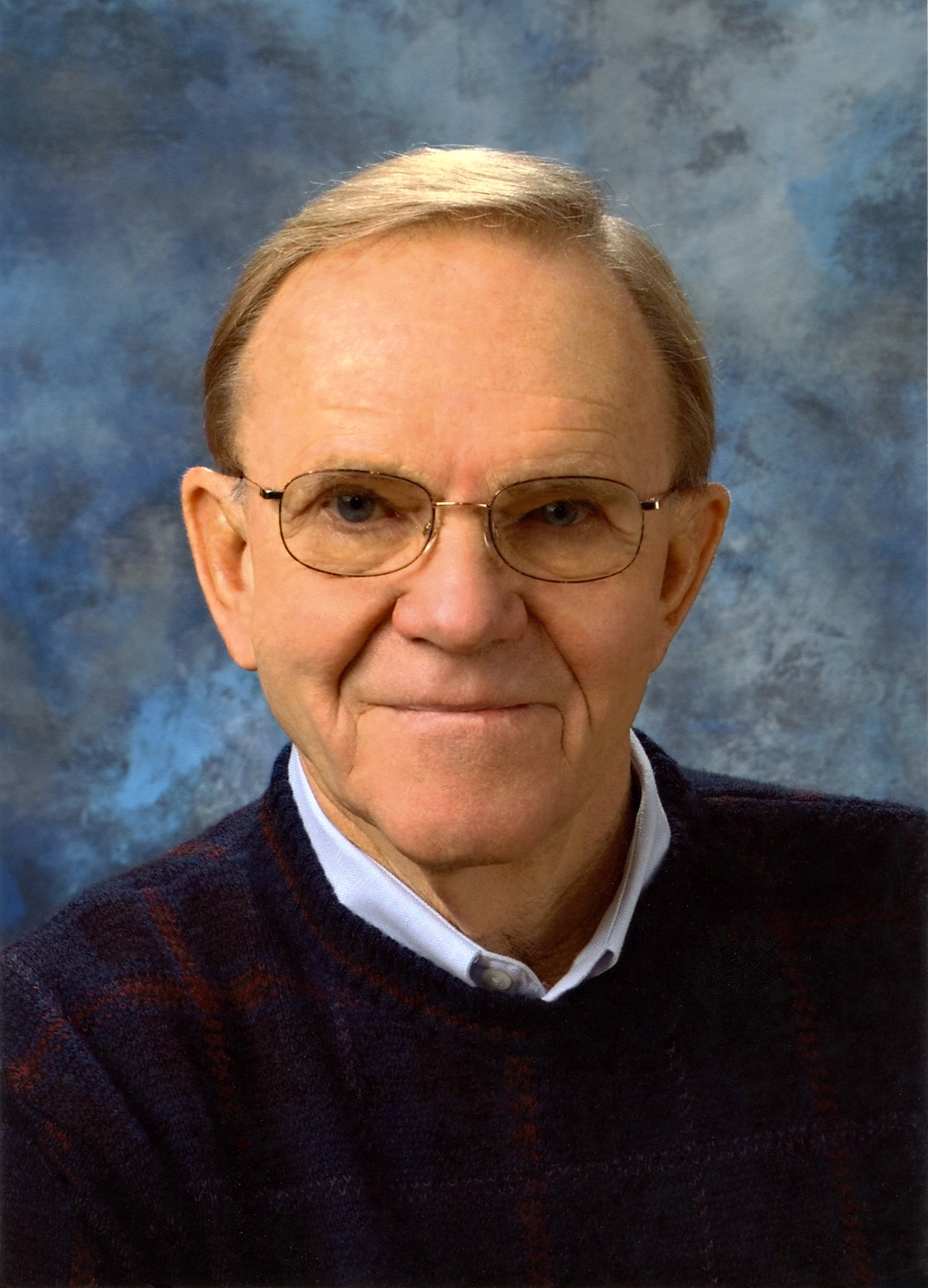

Deborah Golino

Deborah Golino received her Bachelor of Science degree from UC Riverside in 1974 in Plant Sciences. She thereafter achieved Master’s (1983) and Doctoral (1987) degrees in Plant Pathology from UC Riverside. While studying in her graduate programs, Golino was employed as a technician and USDA researcher in the USDA-ARS (Agricultural Research Service) Boyden Fruit and Vegetable Insects Laboratory at UC Riverside where she performed basic and applied research on arthropods that transmit pathogens of fruit trees. Her thesis was based on her work at the entomology laboratory on vectors for phytoplasma/bacteria on citrus.

Golino had begun to work her way up the federal GS system while at UC Riverside. In the 1980’s, the USDA-ARS had begun to downsize the number of researchers around the country and cut the budgets for agricultural research. The pool of ARS researchers around the country had been halved in the prior 20 to 25 years. The Boyden Entomology Lab was closed in 1987, and the scientists were transferred.

Golino’s USDA area director, Bill Chase, was acquainted with Dr. Bob Webster in the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis and saw that Golino was transferred to Davis. She agreed to work with grapes, manage the grape imports and oversee the testing at FPMS in light of Goheen’s retirement. She was transferred from Riverside to Davis in 1987.

As was Austin Goheen, then-USDA scientist Golino was initially associated with the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis. Her assignment included research on virus and virus-like diseases of grapes and development of virus elimination techniques. She was immediately appointed to the FPMS Grapevine Technical Advisory Committee. 9 Minutes, FPMS Grape Subcommittee Meeting, November 17, 1987, included in 1988 FPMS Annual Report, Foundation Plant Services collection AR-050, box 29: 49, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; “New USDA Research Plant Pathologist at UCD”, FPMS Newsletter, number 7, November 1987, p. 2.

The reinstatement of the grapevine importation program at FPMS was a matter of some urgency to the grape and wine industry. After Goheen decided to retire in 1986, grape importations at FPMS ceased. He had stopped processing the quarantine selections in anticipation of retirement. FPMS distributed Goheen’s collection of approximately 700 grape selections from the Plant Pathology facilities to facilities managed by FPMS, the Department of Viticulture & Enology, and the NCGR in the winter and spring of 1987. FPMS assumed responsibility for holding the selections that were scheduled to be indexed in 1987-88 and all selections that remained in quarantine at that time.

Demand for imports increased as new work was being done at programs in Europe. Growers and nurserymen were unhappy and lobbied for a replacement for Goheen. The quarantine hiatus in California encouraged illegal clonal importation activity, which reached an all-time high; much needed screening and indexing processes were often by-passed in favor of quick, potentially dangerous illegal entry. 10 Alley, L. and D.A. Golino. “The Origins of the Grape Program at Foundation Plant Materials Service”, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000, pp. 227-228; “Grape Program Changes”, FPMS Newsletter, number 8, November 1988, at pp. 3-4.

Golino’s commitment in 1987 to oversee the FPMS work was a welcome solution to the void created by Goheen’s retirement. In October of 1988, she indicated to the FPMS Industry Advisory Committee a willingness to serve as scientific administrator for a grape quarantine program at FPMS, to familiarize herself with the laws and science involved and to develop protocols. She agreed to apply for an importation permit in her name when [Goheen’s] prior permit expired in July of 1989.

At the time, Golino expressed a reservation about the fact that a permit came without any funding or facilities to support a federal quarantine program. She stated an intent to seek funding from USDA-APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) to do the quarantine work at FPMS. Golino also voiced her opinion that FPMS needed additional facilities (greenhouse, screenhouse, field plot, laboratory, environmental control chamber) and staff to implement an active program. 11 Minutes, FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee Meetings, October 7 and 19, 1988, Foundation Plant Services collection AR-050, box 23: 12, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; “Grape Program Changes”, FPMS Newsletter, number 8, November 1988, at pp. 3-4.

There were only three permit holders for grape importation in the United States in 1988: David Cameron at OSU (Oregon State University); Dennis Gonsalves at Cornell University, New York; and Goheen at Davis. Cameron’s permit at OSU was dependent on his ability to send his quarantine material to Davis for the leafroll index, and he had stopped accepting new materials. 12 Minutes, FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee Meeting, October 7, 1988, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 12, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; Minutes, FPMS Grapevine Advisory Committee Meeting, January 10, 1986, AR-050, box 23: 11. The reason for a shortage of permit holders was that only research scientists associated with a university or a publicly-funded research organization (USDA/ARS) could hold departmental permits for importation. 13 Deborah Golino, “Grapevine Importation: the process and the problems”, Practical Winery & Vineyard, May/June 1989, pp. 81-84.

Only two grape centers in North America were actively processing imports through quarantine in the 1980’s: (1) Cornell University in Geneva NY and (2) the Canadian Food & Inspection Agency in Saanichton, British Columbia. A scientist at Missouri, R. N. Goodman, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Missouri, received an importation permit for grapes for the Fruit Experiment Station at Mt. Grove (SW Missouri State University) in 1994. 14 Letter from R.N. Goodman, Adj. Res. Prof. University of Missouri-Columbia, Adj. Prof. Fruit Experiment Station, Mt. Grove, to Susan Nelson-Kluk, Manager, dated September 27, 1994, on file at FPS.

Grape industry members in California were eager to reinstate the quarantine program at FPMS and supported Golino’s proposals by way of an industry resolution to the California Department of Food & Agriculture (CDFA) on November 16, 1988. The FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee endorsed the idea of a new quarantine facility and program. The Committee asked FPMS staff for a plan for release of [Goheen’s] pending plant material, including the Winegrowers’ clones [see below], within the following two years. FPS Advisory Committee member, grower and winemaker Phil Freese noted that the best way to improve FPMS public relations would be to efficiently import and release new foreign grape selections. 15 Minutes, FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee Meetings, October 7 and 19, 1988, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 12, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The transition from Goheen to a new permit holder would not be without a few roadblocks. Golino was a young research scientist and, as such, was expected to perform research and to publish to advance within the federal agency. Her administrators at USDA-ARS initially told her she could not hold the importation permit for the work at FPMS because her job was to do research, and service work was not part of the ARS mission.

The California grape and wine industry, including interested parties such as Rich Kunde and Phil Freese, had put pressure on Congress and the USDA-ARS to ensure that Austin Goheen was replaced. They did not understand that replacement of Goheen did not necessarily mean FPMS would inevitably be granted a USDA scientist to do the FPMS work. FPMS staff were initially upset that Golino would not be allowed to acquire a new permit and that imports would not resume. Apart from the permit and staffing issues, Golino felt that FPMS could not do effective quarantine work without proper facilities. 16 Alley, L. and D.A. Golino. “The Origins of the Grape Program at Foundation Plant Materials Service”, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000, p. 227.

APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) is a co-equal sister department of ARS within the USDA. APHIS provides oversight on the importation and quarantine regulations in the United States and establishes guidelines and issues permits allowing importation of grapevine material into the country. While the USDA-ARS initially denied Golino permission to hold a permit for the FPMS program, Director Joseph Foster at the APHIS National Plant Germplasm Quarantine Program informed her that someone qualified as a scientist acting for FPMS would need to be named on the new permit before an importation program could be restarted. The FPMS program was between a rock and a hard place in 1988.

The concept of the APHIS “Departmental Permit” was described in the prior chapter (“Origin of Foundation Plant Services”). USDA Departmental Permits were issued to qualified scientists at places like universities and other government agencies to bring prohibited plant materials into the United States for research under strict conditions through regulated importation and quarantine facilities. Dr. Joseph Foster felt that issuance of an importation permit in the name of a person at a certain institution rather than the institution itself would provide greater responsibility and accountability. 17 Interview with Erich Rudyj, Coordinator, National Clean Plant Network, USDA-APHIS, on September 22, 2017.

In February, 1989, Golino informed the FPMS Technical Committee that USDA-APHIS policy would not permit transfer of quarantine materials previously imported under Goheen’s permit to Golino’s custody unless the name of a qualified plant pathologist was on the departmental permit issued to FPMS. Goheen’s permit was set to expire in 1989. 18 Minutes, FPMS Technical Committee Meeting, February 3, 1989, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 12, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The impasse was resolved in 1990 when Golino was awarded a Departmental Permit (No. 61201) to test and qualify for release Vitis accessions imported by Goheen under his old Departmental Permit (No. 57319). The accessions previously on hold at FPMS were released for disease testing and treatment.

Golino was eventually awarded a Departmental Permit in her own name (no. 61541) in 1991-92 for new importations of grape varieties and clones into the United States. USDA-ARS agreed that Golino could hold the grapevine importation permit in her name “as long as she didn’t do any of the work” at FPMS and instead did her research work. [Golino was later reissued another Departmental permit in 1995 to reflect her change of status to Director of FPMS.]

Grape importation through FPMS would not resume until the 1992-1993 season, about the time a new FPMS facility with appropriate equipment was finally constructed. 19 Alley, L. and D.A. Golino. “The Origins of the Grape Program at Foundation Plant Materials Service”, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000, p. 227.

A new Director at FPMS

The University of California conducted a national search to fill the new Director position at FPMS beginning in 1993. Numerous qualified candidates were considered. Deborah Golino had been working with FPMS for years by that time and was familiar with the scientific and technical issues and funding problems experienced by the program. She had the requisite PhD in Plant Pathology to qualify under the USDA regulations for a grape importation permit and years of experience with the USDA researching plant pathogens.

The committee offered the FPMS Director position to Golino. She was a young research scientist in an atmosphere where research, teaching and publishing were normally required for advancement. Golino recognized the tension between the “twin goals of discovery and service” when she arrived in the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis in 1987 as a USDA-ARS scientist. The decision to accept the position presented a dilemma.

FPS has its historic roots in UC Davis faculty research programs on viruses of cherries and grapevines in the 1950’s. At that time, creating clean plant material by screening for viruses was cutting edge science. As the years passed, this important work became less part of a modern research program for faculty and more of a service program for industry. The challenges faced in continuing the work of the clean plant centers at universities arise in part from the traditional dichotomy between research and service work, frequently resulting in short-changing the service component. USDA scientist Austin Goheen had made sacrifices in terms of career advancement for the service work he performed at FPMS from the 1960’s through the 1980’s.

The clean plant and outreach work at FPS were considered service work by the time Golino interviewed for the Director’s position. The grape and wine industry that had lobbied for her position at FPMS were most interested in that FPMS service work. The dilemma she faced was ultimately resolved when Golino accepted the Directorship at FPMS in 1994 notwithstanding the possible professional and financial challenges.

University centers with faculty members in the Director position often did not give the Director adequate time to complete the service work as well as meet expectations for research, teaching and other academic work. UC Davis attempted to remedy that situation when they hired Golino as the new Director for FPMS in 1994. The funding structure for the Director position was established with an eye toward value for service work.

UC Davis committed a faculty administrative position to serve as FPMS Director. Golino was hired to fill that position. The position description for the FPMS Director assigned 70% of the Director’s time to the Academic Administrator title (College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences) and 30% to the Cooperative Extension Specialist title (Agriculture & Natural Resources). With those faculty titles, it would be possible for the new Director to have career success while administrating service work.

Service work is highly valued by the industry stakeholders, who demonstrated their commitment by substantial funding commitments to the FPMS program. The industry group IAB (California Fruit Tree, Nut Tree and Grapevine Improvement Advisory Board) was established in 1988 to promote production of high-quality tree and grapevine nursery stock. The IAB committed to providing 40% of the new faculty Director’s salary and benefits.

Golino officially assumed the Director position at FPS on November 1, 1994. The new Importation & Quarantine Facility was built and opened the same month.

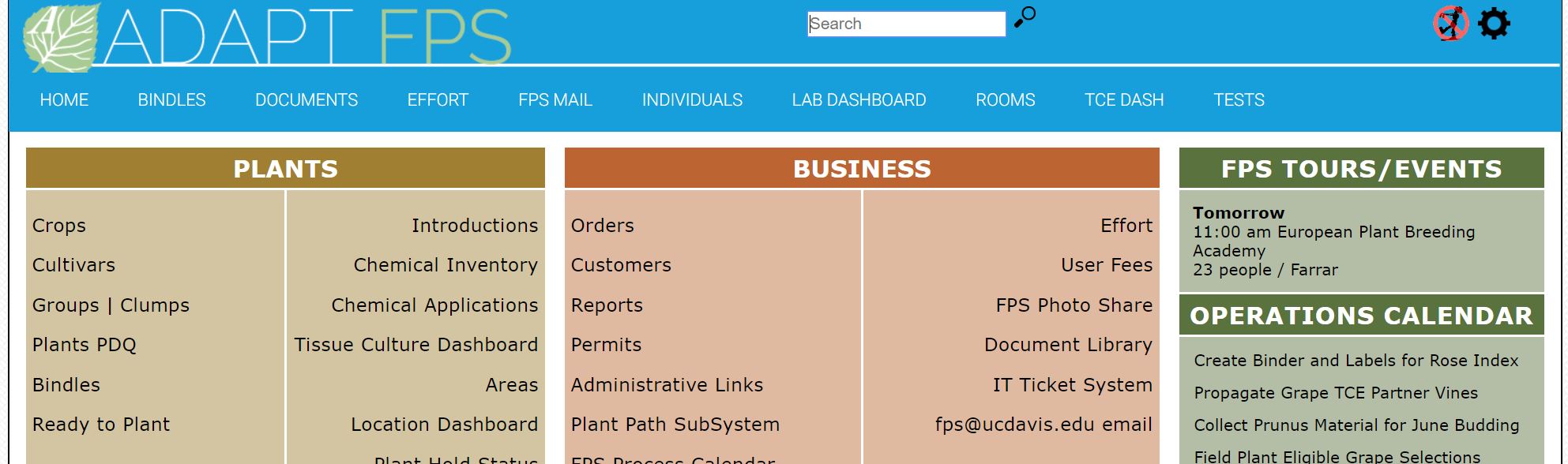

As recommended in the 1992 Task Force Report, Golino organized the center into crop units when she was appointed Director of FPMS. She appointed specialists from the FPMS staff as Managers for the various crops: Susan Nelson-Kluk for the Grape Program; Mike Cunningham for the Tree and Rose Programs; Golino for the Strawberry Program. 20 Message from the Director, Newsletter, Foundation Plant Materials Service, no. 14, November 1995, page 1. Adib Rowhani was assigned to head the FPMS plant health section, and Cunningham was charged with overall responsibility for all plant materials maintenance, propagation and distribution.

The Task Force also recommended more direct involvement with FPMS by the faculty of the University departments that had research and extension responsibilities for the crops handled by the center. UCD Viticulture & Enology Professor Dr. Andy Walker had served as Interim Associate Director for Viticulture at FPMS since November 1, 1993, during the search for a new FPMS Director. On October 18, 1994, Golino requested that Walker remain in that capacity for frequent input and consultation on viticulture matters particularly related to ampelography and identification of the FPS foundation collection. 21 Memo from Deborah Golino, FPMS Director, to all FPMS Advisors, dated October 18, 1994, FPS collection, AR-050, box 23: 14, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The Task Force Report recognized the significant service work the FPMS grape program had performed for California agriculture in the past, benefitting the industry enormously by increasing vineyard productivity and fruit quality. The Task Force found that the grape program had been the most financially solid of the FPMS programs over the prior 30 years, generating enough income to cover its operating costs in most years. A major factor in the profitability projection for the future was the introduction of “new products”, i.e., grape scion and rootstock selections that would be processed through the new National Grapevine Importation and Clean Stock Program beginning with the first imports in 1992-93. That program would be required to generate its own operating revenue. 22 1992 Task Force Report, supra, at p. 12.

Phil Freese, then Vice-President at Mondavi Winery, was one of the co-chairs of the Task Force and a long-time industry advisor to FPMS/FPS. He entered the grape and wine industry in the late-1970’s with a doctorate in the biological sciences (biochemistry and biophysics) from UC Davis. Freese would eventually establish his own consulting and winery business, WineGrow, with plantings on multiple continents. Freese and his wife, respected winemaker Zelma Long, established Vilafonte Vineyards in Stellenbosch, Western Cape of South Africa.

Freese saw the Task Force project as a tale of government, academics and industry working together to produce a platform that continues to refresh itself and adapt to evolving needs. His close association with FPMS/FPS over the years has led him to conclude that the University and industry collectively came together to establish a successful framework for the future.

Freese indicates he was fortunate to have had the opportunity to spend a lot of time with Austin Goheen, who was dedicated to the theory of working with “clean materials and keeping them clean”. Freese also saw that the late 70’s and into the 80’s was a time of strong demand to bring in different clonal selections and varieties and to broaden the reservoir of different rootstocks. He recalls the words of his mentor, Robert Mondavi: “Wine characters and styles were driving the industry in its full-on pursuit of production of ‘wines that would stand in the company of the wines of the world’.”

Freese saw Austin Goheen’s retirement as a threat to the continued sanitary health of the FPMS grapevine collection. At the same time, there was a new and emerging need for additional clonal materials. The university program needed everything in the late 1990’s – propagation and dissemination of tested materials, scientific research into previously unknown or uncharacterized diseases, awareness that California was not using all the available rootstocks and scions and yet was striving to compete to the higher standard of wines of the caliber of the rest of the world. This “new era” required maintaining previous capacities while building on new capabilities in the future.

Given the funding shortage faced by the University, this “new era” required new solutions driven by an individual that could assume a wide variety of professional challenges. Freese saw that FPMS needed leadership, scientific knowledge and a research direction to address existing and future issues, as well as a great manager, team builder, a person with academic credentials and “research gravitas”, who could work effectively in both the academic and the grower’s worlds. He states that Golino was exactly the “right person in the right place at the right time to take on the future” of the FPMS/FPS program.

Much remained to be done by way of outreach to the grape industry once the new FPMS team was in place. Long-time Production Supervisor Mike Cunningham felt that FPMS needed a Director with political acumen who could anticipate and adjust to future industry needs. When FPMS had been part of the umbrella unit FSPMS, the Directors Burt Ray, Cal Qualset and Bob Ball were more agronomically oriented and spent much time with the seed work and less with the clonally-propagated crops. Cunningham saw that Golino had a practical streak resulting in focus on big picture issues and results. She also possessed exceptional communication and networking skills that facilitated strong relationships with members of the grape and wine industry.

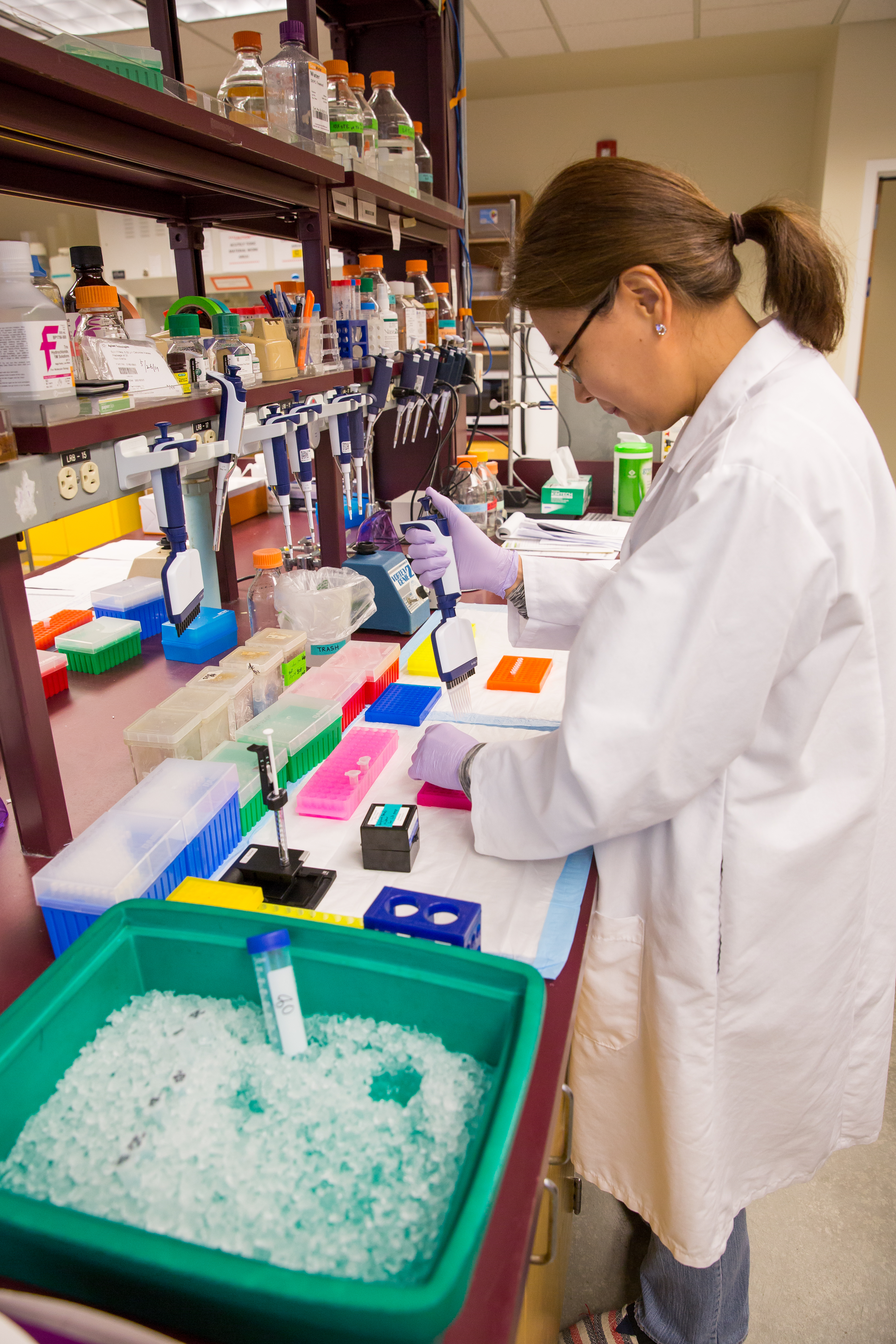

Golino quickly grew into the Director position at FPMS. As the center moved into the new facility, she hired more people, and the state-of -the-art laboratories came to life. Disease testing and treatment made significant advances to upgrade the plant material. New imports and domestic accessions greatly diversified the foundation grapevine collection. The technology and outreach media underwent significant overhaul, mostly in the years after 2010. The following topical threads illustrate the significant initiatives and improvements over which Golino presided as Director of FPMS/FPS.

GRAPEVINE IMPORTATION & QUARANTINE FACILITY (1995)

“The National Grapevine Importation Program began in 1995 as a result of a cooperative effort by UC, the USDA, CDFA, and the grape industry. The new program included a new importation and quarantine facility, state of the art laboratory facilities for disease testing and variety identification and field facilities and vineyards.” -- FPMS Grape Importation brochure.

From 1995 through 2018, more than 2,100 new grape selections were introduced at FPS, including new foreign and domestic varieties, clones and rootstocks, plus germplasm intended for research. The quarantine facility completed in 1994 and dedicated in 1995 made that result possible.

FPMS had ceased accepting new grape material from foreign and domestic sources prior to 1989. No disease elimination work to clean up accumulated quarantine selections had been done since Goheen’s retirement. The quarantine grapevine material received by Goheen under his permit had been languishing for years in the Department of Plant Pathology field facilities and the greenhouses at the National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Davis. There was a backlog of more than 300 grape selections known to be diseased and needing treatment in Davis before they could be released from quarantine. Valuable quarantined material already collected by Harold Olmo and others was in danger of being lost because of the makeshift nature of the FPMS facilities in which the material was held after Goheen’s retirement.

The Department of Plant Pathology had indicated an intention to reassign the facilities and field space used by Goheen for his work on quarantine processing. The existing facilities at FPMS were completely inadequate to house a grape importation and quarantine program in 1989. Structures appropriate for isolation of quarantined grapevine material were needed prior to any importations under a new permit. FPMS did not have adequate facilities to maintain on an indefinite basis the selections that had been accumulated by Goheen.

The grape and wine industry was anxious to assist with a solution. The FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee recommended that FPMS increase prices for grape materials (October, 1988) and reinstate user fees for additional income (May, 1989). Influential Advisory Committee members such as Phil Freese and Zelma Long shared the vision for a new facility and provided invaluable support in securing federal and industry funding. Deborah Golino travelled to local growers meetings around California educating on the need for new FPMS testing and treatment facilities before grape importations could be resumed.

In April of 1989, FPMS submitted a proposal to the USDA requesting funding for a Grapevine Importation & Quarantine facility at UC Davis. The goals were to provide importation services for commercial grape growers and researchers and to protect the U.S. grape industry from introduction of dangerous foreign pathogens. 23 Susan Nelson-Kluk, “Grapevine importation revived at FPMS”, Practical Winery & Vineyard, September/October 1992, pp. 22-23. The proposal was submitted to the USDA too late to obtain funds from the USDA budget for federal fiscal year 1989-90.

Winemakers Robert Young and Louis Martini approached Congressman Vic Fazio for assistance. Fazio placed an allocation of $130,000 for design and planning activities in the House of Representatives agriculture funding bill for 1989-90. Although the Senate removed the item from the budget bill, it was reinstated by a House/Senate conference committee in October, 1989, after a vigorous letter writing campaign conducted by the industry. 24 “FPMS Grape Importation Project”, FPMS Newsletter, no. 9, November 1989, page 2. FPMS was ultimately provided with $124,160 from the 1990 federal budget for design and planning of the new facility. 25 “Grape Program Report”, FPMS Newsletter, no. 10, November 1990, page 1.

The $3.5 million building project was ultimately funded jointly by the federal government, the University and private industry. Industry advocacy efforts, organized by winegrower Phil Freese, resulted in appropriations from the federal budget to FPMS of $870,090 (1991), $1,610,000 (1992) and $582,000 (1993) for a National Grape Importation and Clean Stock Facility.

The USDA required partial matching funds for the project. The industry group IAB (California Fruit Tree, Nut Tree and Grapevine Improvement Advisory Board) donated $125,000 for a quarantine screenhouse and $180,000 for a portion of a greenhouse. 26 “Grape Program Report”, FPMS Newsletter, no. 10, November 1990, page 1; IAB Board Minutes, April 1992, Foundation Plant Services collection AR-050, box 34: 7, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis . The University made contributions in funds, staff services and land to make up the balance needed. 27 Letter from Phil Freese to Grape Industry Members dated October 14, 1991, reprinted in FPMS Newsletter, number 11, October 1991, p. 2; “National Grapevine Importation Program”, FPMS Newsletter, no. 12, November 1992, p. 3.

FPS’ dire need for its own dedicated quarantine structures was about to be satisfied. A new facility was constructed in phases between 1990 and 1994 at the corner of Hopkins and Straloch Roads west of the UC Davis campus. FPMS Manager Susan Nelson-Kluk performed an important role as liaison between UC and the USDA during the planning and construction of the facility. The official ground-breaking ceremony for the new facility was held on June 1, 1992.

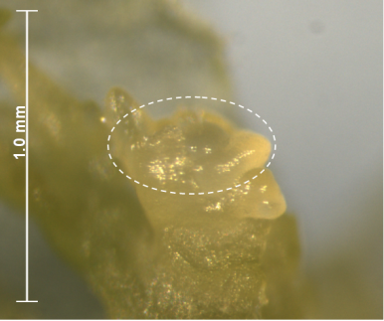

Phase I of the project included completion of facility planning as well as construction of outbuildings – a quarantine screenhouse and strawberry clean stock greenhouse in 1990. One small setback occurred when the sodium lights were stolen from the strawberry greenhouse by suspected pot growers. A primary quarantine greenhouse, indexing greenhouse, soil storage area and headhouse were completed as Phase II in November 1992. Those facilities made it possible for FPMS to import foreign grapevine materials and perform disease testing. Grape importations resumed in the 1992-1993 dormant season.

Phase III saw completion of the laboratory/office area and second screenhouse in 1992. Construction of the laboratory was necessary before FPMS could perform disease elimination treatments. A second indexing greenhouse, landscape irrigation, and all fixed equipment were completed in 1993 in Phase IV.

The new facility was occupied in September, 1994. The initial design plans proposed a vibrant and, some thought, “garish” color scheme for the building, which eventually was muted to rose and purple to evoke the colors of grapes. The new facility was a 15,620-square foot complex including laboratories, business offices, screenhouses and greenhouses. The modern laboratory facilitated expansion of existing services and space to conduct research for improving disease detection and disease elimination technologies. An open house and dedication of the facility was held on April 21, 1995. 28 Alley, L. and D.A. Golino. “The Origins of the Grape Program at Foundation Plant Materials Service”, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000, p. 228.

The first foreign grapevine material since 1989 was imported in the winter of 1992-93 and began the testing process at FPMS in anticipation of release from quarantine. Those imports included 40 selections from France and Italy that were sponsored with IAB funds accumulated through assessments on nurseries participating in the California R&C Program. 29 Susan Nelson-Kluk, “Grapevine importation revived at FPMS”, Practical Winery & Vineyard, September/October 1992, pp. 22-23; FPMS Newsletter, no. 12, November 1992, p.3; FPMS Newsletter, no. 13, October 1993, p.3.

NEW DIRECTIONS IN DISEASE TESTING AND TREATMENT

“The focus of the FPS grape program is to produce the highest quality virus-tested and true-to-variety plant materials, using state-of-the-art technology” --Deborah Golino, Challenging Times Ahead for FPS, FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2003

The key to improving the health status of vineyards in the state is selecting and supplying the highest quality of plant material to the industry. 30 Golino D.A., M. Fuchs, S. Sim, K. Farrar, and G.P. Martelli, “Improvement of Grapevine Planting Stock Through Sanitary Selection and Pathogen Elimination”, Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, Chapter 27, p. 561, eds. B. Meng, G.P. Martelli, D.A. Golino, M. Fuchs (Springer International Publishing AG 2017). Significant changes in disease testing and treatment introduced at FPS in the 1990’s resulted in a much more consistent output in terms of phytosanitary standards. Quality control standards have been much improved. The advancements in disease testing technology developed since the 1980’s and improvement in quality control standards have transformed the nature of foundation grapevine material available at FPS in 2019.

The early FPMS efforts in disease testing and treatment, some of which are still used today for field index testing at FPS, are fully described in the prior chapter, “Origin of Foundation Plant Services”. Two scientists were added to the FPMS team in the late 1980’s. They directed significant upgrades in those early testing and treatment protocols. Dr. Adib Rowhani developed and implemented new technologies for more effective detection of grape viruses beginning in 1988. Dr. Deborah Golino eventually became FPMS Director. Golino and Rowhani added significant expertise and direction to the floundering program.

Adib Rowhani

Bob Webster was the Chair of the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis from 1984 to 1989. It was a time of budget cuts at the University, and major changes were being made in the way campus funds were being used to support faculty. For many years, Plant Pathology farm staff had planted and maintained the field virus index for FPMS, even though FPMS was no longer part of the Plant Pathology Department. Webster discontinued that tradition, asking FPMS staff to assume responsibility for the field index themselves.

In addition, at about the same time, Austin Goheen retired from the USDA-ARS. With his retirement, there was an end to the virus testing and heat treatment therapy provided to FPMS by Goheen and his technician, Carl Luhn.

Amid those major transitions, Webster took a step to ensure that FPMS work was continued despite the loss of resources. He successfully lobbied the Dean’s Office (College of Agriculture & Environmental Sciences, UC Davis) for funding for a dedicated Plant Pathology Specialist position to provide much needed technical support to FPMS. That faculty member would be responsible for overseeing accurate virus testing and effective disease elimination therapy for the FPMS program. Dr. Adib Rowhani was hired in spring of 1988 to fill that position.

Rowhani received his Bachelor of Science degree in Plant Protection from the University of Shiraz in Iran. He earned his Master of Science degree in Plant Pathology from McGill University in Montreal (1977) and PhD degree in Plant Pathology with emphasis on virus diseases from University of British Columbia (1980).

Rowhani arrived at UC Davis in 1980 for a post-doctoral position in the Department of Plant Pathology. He chose UC Davis because of the prestige and world-wide reputation of the Department. Rowhani explained that the move in 1980 from the large, cosmopolitan city of Vancouver, British Columbia, to the then-small village of Davis was unsettling at first. At the time, Davis had only two or three stoplights. Wheat and alfalfa were grown in the area where the busy thoroughfare of Covell Boulevard now exists. West Davis consisted of fields and crops. 31 Author interview of Dr. Adib Rowhani, January 29, 2018.

From 1980 to 1988, Rowhani studied the etiology of blackline walnut disease with Dr. John Mircetich. Rowhani was experienced with cutting edge virus disease testing technologies including ELISA, dsRNA extraction, virus purification and antiserum production. He cooperated with scientists nationwide on protocols for grape, fruit and nut tree and strawberry disease testing techniques. 32 “New Staff at FPMS”, Newsletter, Foundation Plant Materials Service, University of California, Davis, number 8, November 1988, p. 2.

Rowhani was approached about the FPMS specialist position about 1987 or 1988. The College of Agriculture conducted a national search and interviewed four candidates. Rowhani was ultimately selected and started at FPMS in spring, 1988, when FPMS was still one unit within the larger entity FSPMS (Foundation Seed & Plant Materials Services, see prior Chapter “Origin of Foundation Plant Services”).

When Rowhani started at FPMS, there were only four or five employees, including the Manager (Susan Nelson-Kluk), the Production Manager (Mike Cunningham), field supervisor (Matt Gallagher) and office staff (Cheryl Covert). Rowhani’s position was Director of Laboratory Operations, responsible for oversight of the health status of FPMS plant material

Rowhani spent time with Austin Goheen for about one year when Goheen was approaching retirement at UC Davis. Rowhani shadowed Goheen during that time and learned much about grapevines, especially about field indexing and inspections. He worked as staff Plant Pathologist on all crops at FPMS, primarily grapes and trees.

At the time Rowhani started at FPMS, the foundation grapevines included in the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program were planted in the Hopkins Road Foundation Vineyard as well as in the Department of Viticulture vineyards further south off Hopkins Road. The “Hopkins Road foundation vineyard” was located near where the parking lot adjacent to the current UC Davis Mail Division facility is situated. The foundation vines in the Hopkins Road vineyard and Viticulture vineyard were interplanted with vines that suffered from virus and vines that had not been tested for disease.

The Department of Viticulture vines ended up in the certification program out of necessity. If a grower wanted a particular variety that was not already included in the FPMS Hopkins Road foundation vineyard, Goheen would identify a vine of the desired variety in the Department of Viticulture vineyard, index it and include it on the CDFA list of registered (foundation) materials if the results were negative. When CDFA came to do the required inspections of foundation vines, the inspectors, Goheen and Rowhani would first look at the vines in the FPMS Hopkins vineyard and then find and inspect the “foundation vines” interspersed in the Department of Viticulture vineyard. Rowhani indicates that the inspections took a very long time.

Although the FPMS “foundation vineyard” west of Hopkins Road included certified grapevine selections in the late 1980’s, to Rowhani’s eyes, many of the vines were obviously diseased. The 20- to 30-year old vines were head trained on posts and exhibited symptoms of trunk and virus disease and eutypa. Diseased vines were growing next to apparently healthy vines. Rowhani describes many of the diseased vines as “really miserable” in appearance.

Charbono in Hopkins vineyard, 1980’s |

Lagrein in Hopkins vineyard, 1980’s |

Goheen did not believe that the sickly vines suffered from viruses. He believed that the sickly vines were the product of poor cultural practices and phylloxera. 33 Interview with Adib Rowhani, January 29, 2018. At that time, the science was not clear on whether virus spread from vine to vine and on mealybug’s role in that spread. Goheen believed that leafroll viruses did not spread vine to vine, and the UC Davis vineyards were managed with that philosophy. Additionally, foundation vines were not habitually retested since it was believed that virus did not spread and there was no need for retesting once a vine tested negative for virus. The discovery that mealybugs spread leafroll virus was not generally accepted until the early to mid-1990’s.

Traditional field index and herbaceous host index testing were the only tests used on grapevines for the California Grapevine R&C Program at FPMS when Rowhani was hired in 1988. He initiated a major upgrade in disease testing around 1990 after Goheen retired. Rowhani developed a laboratory program to implement newer, more sensitive, faster, and cheaper testing methods for screening plants for grape diseases. 34 “RSP and the CA Grapevine R&C Regulations” FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2000, page 7.

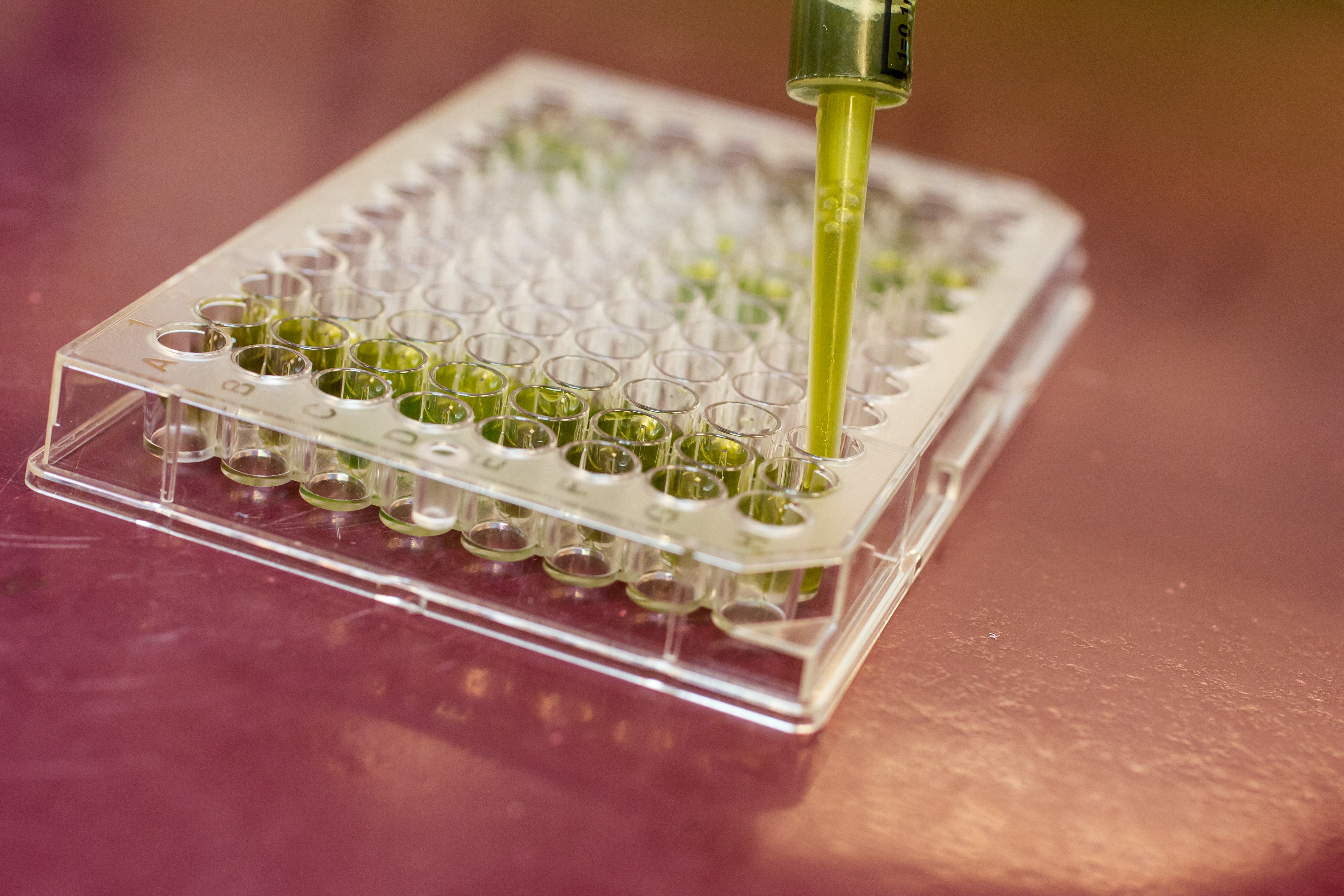

The first major molecular test Rowhani implemented at FPMS was the “ELISA test”, which screened for a range of suspected “known” viruses and virus strains. The enzyme linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) is a rapid, cost effective serological test for detecting viruses in woody plants. ELISA has its limitations, one of which is that the test lacks the sensitivity to reliably detect viruses when they occur in low titers.

|

|

Additionally, the highly purified virus preparations required to produce antisera needed for the ELISA test were often difficult to obtain in the late 1980’s. 35 Adib Rowhani, “PCR for the Future”, FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, October 1999, page 9. At the outset, Rowhani obtained the antibodies needed for grapevine testing for leafroll virus from Plant Pathologist Dennis Gonsalves at Cornell University in New York. Rowhani then purified his own virus at FPMS. Notwithstanding the limitations, the ELISA test proved to be an effective detector of virus in FPMS grape material in the 1990’s.

Disease threats to FPMS vineyard

Rowhani’s skills would be tested by serious disease issues affecting the FPMS grapevine collection in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Two major setbacks were experienced when serious viruses threatened the clean plant program in 1989 (fanleaf degeneration) and 1992-93 (leafroll virus). Fanleaf degeneration and leafroll virus are two of the most destructive diseases to grapevines. Industry confidence in FPMS’ ability to provide grape material free of viruses was shaken by the two episodes. Rowhani was instrumental in sorting out the problems.

Fanleaf virus

In 1989, fanleaf infection was found in San Joaquin County in certified stock released through the California Grapevine R&C Program. Rowhani was at the time developing the fanleaf ELISA testing protocol for FPMS. It was not until an ELISA test for fanleaf virus was available in the 1980’s that FPMS realized that the fanleaf virus had passed through the index process undetected in foundation grapevine material.

When the fanleaf virus was discovered in a certified grape nursery in San Joaquin County in 1989, CDFA required that FPMS test the entire foundation vineyard for fanleaf virus using the new technology before it would allow any of the vines to continue to be registered. ELISA testing can be an effective diagnostic tool for certain diseases such as fanleaf degeneration where a single virus or bacterium is responsible for causing disease. FPMS subjected all the registered foundation vines and non-registered blocks to ELISA testing in 1990. The culprit turned out to be Nebbiolo fino 01, which was the only FPMS selection that tested positive for fanleaf virus. 36 Minutes, FPMS Viticulture Technical Committee Meeting, August 3, 1990, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 13, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

Nebbiolo fino 01 attained registered status in the Grapevine R&C Program in 1970 by testing negative for all the prohibited viruses on the field index test. The selection was planted in the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard in 1966 (F12 v13-14) and in the Brooks South Foundation Vineyard in 1984 (BKS G6 v9-10). The original material had been collected from the old UC Foothill Experiment Station vineyard near Jackson, California.

The mother vines for the Nebbiolo fino budwood were the suspected source of the infection. FPS Program Manager Curtis Alley had had a problem during the index testing process. Somehow the original Nebbiolo budwood was combined with another selection from a different source vine that had the same number of heat treatment days. Nebbiolo fino 01 tested positive for fanleaf virus at FPMS on July 2, 1990, using the new ELISA testing method. The Nebbiolo fino 01 vines were removed from the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard and from the Brooks South Vineyard. 37 “Testing of the Foundation Vineyard for Fanleaf Virus with ELISA”, FPMS Newsletter, no. 10, November 1990, p. 2.

CDFA tested all increase blocks in the R&C Program and advised all nurseries and growers to tell their customers about the fanleaf problem. The discovery of fanleaf virus necessitated a review of the entire program. CDFA was concerned with brokering sales between nurseries, replants and top-working on increase blocks, tracking sales of FPMS material and transferring certified material between participants in the program. 38 Report from FPMS Technical Advisory Committee, April 23, 1990; Minutes, FPMS Grape Subcommittee Meeting, December 13, 1989, included in 1990 Annual Report; both documents on file in FPS collection AR-050, box 29: 49, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The fanleaf issue did cause consternation amongst nurseries and growers. FPMS Grape Program Manager Susan Nelson-Kluk saw a positive side to the crisis. She believed that the episode significantly increased nursery awareness of viruses due to the extensive testing conducted for fanleaf virus in 1989-1990.

Leafroll virus

The fanleaf scare was followed a few years later by discovery of leafroll virus in the FPMS vineyard. Rowhani had worked since 1988 on developing ELISA testing for leafroll detection in FPMS vines. In 1992, he tested one vine of each registered grape selection in the FPMS foundation vineyards for three leafroll associated viruses using the recently-developed ELISA technology. Molecular tests for virus are specific to each virus, so a separate test was developed for each leafroll-associated virus. The results of the testing caused much upheaval in the industry.

In October of 1992, Rowhani reported to the FPMS Grape Technical Committee that preliminary testing revealed approximately 20% of the rootstock and scion foundation vines tested positive for grapevine leafroll virus, mostly strain 3. 39 Memo dated October 2, 1992, covering Minutes of Grapevine Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, September 28, 1992, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 13, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. All the ELISA-positive vines were in the old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard west of Hopkins Road and had been propagated from sources that previously tested negative on the field index test. ELISA technology was still relatively new at the time, so the Committee felt that registration of the vines should not be changed based solely on the preliminary results and that further study was necessary.

CDFA and UC Davis decided not to distribute foundation stock from vines that tested positive using the ELISA testing. Distribution was limited that year to registered vines in the Brooks Foundation Vineyard (BKS and BKN). 40 “Grapevine Leafroll Associated Virus Testing by ELISA”, FPMS Newsletter, no. 13, October 1993, p. 2. The amount of foundation stock available from FPMS in 1992-93 was severely reduced because only foundation vines testing negative for leafroll virus were used to fill orders after 1992. 41 Minutes, FPMS Grape Industry and Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, March 23, 1993, FPS collection, AR-050, box 23: 14, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. In March, 1993, the FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee and Technical Advisory Committee were combined into a single committee named the FPMS Grapevine Advisory Board. Glen Stoller was elected to replace Phil Freese as chair of the committee. Minutes, FPMS Grape Industry and Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, March 23, 1993, AR-050, box 23: 14.

Rowhani recalls that there were many meetings between industry, nurseries, state and university attendees during this period, along with much shouting by unhappy people who had invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in foundation material. Ultimately, CDFA and the nurseries negotiated a two-year grace period to allow the nurseries time to sort through and purge their inventory.

Extensive retesting of the FPMS foundation vineyards was conducted in 1992-1993. Final ELISA results for 1992-93 showed that approximately 1% of the rootstock and 29% of the scion vines in the old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard tested positive for leafroll virus. 13.8% of the scion vines in Brooks North (BKN) tested positive, while only 2.5% of the vines (rootstocks and scions) in Brooks South (BKS) were positive.

All vines in the Brooks blocks had been propagated from the old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. Experts at FPMS concluded that the results suggested the onset of significant leafroll disease in the old Hopkins Vineyard primarily between 1983 and 1988. The 1983 planting of Brooks South resulted in a relatively low level of infection (2.5%), while the 1988 planting of Brooks North resulted in a much higher level of disease (13.8%). 42 Ed Weber, Adib Rowhani, and Deborah Golino, “The Current Status of Leafroll Infections in FPMS Vineyards”, presented at the GRAPEVINE VIRUS & CERTIFICATION ISSUES FORUM, 44th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Enology and Viticulture, June 25, 1993, Sacramento, CA, FPS collection AR-050, box 34: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The leafroll experience raised two important issues related to virus in the FPMS collection. First, the focus in the retesting was on whether scientists could confirm the correlation between the disease “grapevine leafroll associated viruses” and the positive ELISA results. The preliminary testing revealed that ELISA results did not always correlate with results from the Cabernet franc woody index tests. 43 Minutes, Grape Technical Committee Meeting, January 22, 1991, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 13, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

A Grapevine Certification Workgroup composed of industry, University and CDFA scientists was formed to explore further the relationship between Cabernet franc index testing and ELISA testing and other issues. The Grape Certification Workgroup also educated the industry about leafroll virus and ELISA testing by distributing a flier entitled “Disease Testing of California Certified Grape Stock”. 44 FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 13, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The second significant finding established by the 1992-1994 leafroll incident was a new perspective on the spread of leafroll virus in a vineyard. The California R&C Program was guided at the outset by two assumptions about grapevine leafroll disease. The existing scientific opinion before 1992 was that grapevine leafroll viruses spread only by grafting healthy stock with infected stock and that leafroll virus did not spread naturally in vineyards. 45 Rowhani, Adib and Deborah Golino. “ELISA test reveals new information about leafroll disease”, California Agriculture 49(1): 26-29 (1995); Goheen, A.C., W.B. Hewitt and C.J. Alley. “Studies of Grape Leafroll in California”, Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 10(2): 78-84 (1959); Austin C. Goheen, 'Virus Diseases and Grapevine Selection', AmJ.Enol.Vitic. 40(1): 67, 69-70; Minutes from Meeting of FPMS, CDFA and Grape R&C participants, March 18, 1981, filed FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 10, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The second assumption was that the viruses that caused leafroll disease were evenly distributed through infected vines. 46 Rowhani, Adib and Deborah Golino. “ELISA test reveals new information about leafroll disease”, California Agriculture 49(1): 26-29 (1995).

In the early 1990’s, no insect vectors of leafroll were known. Spread of leafroll virus by root grafting rarely occurred in grapevines. Mechanical spread (e.g., with pruning shears) of leafroll virus had never been demonstrated. As a result, mixed plantings (infected/healthy vines) had been tolerated by FPMS in or near the Armstrong and Hopkins Foundation Vineyards and the Tyree Vineyard for RSP-positive selections. 47 Author interviews with FPS Production Manager Mike Cunningham (February 24, 2015) and FPS Grape Program Manager Susan Nelson-Kluk (July 21, 2014). The mixed plantings had been tolerated because there had been interest in maintaining certain leafroll-infected selections, and FPMS vineyard space was limited.

Rowhani believed that there was evidence that leafroll associated viruses were spreading within the old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. The theory was that spread occurred when diseased vines were planted next to healthy wood, and resulting infected wood was then used to propagate vines for planting in the Brooks Vineyards. Rowhani felt that the infection was recent, evident from uneven distribution within single vines. He observed that multiple vines from the same original source vine showed different results. Although he had no evidence of a vector, he felt that it could no longer be assumed that the only way leafroll spread was by grafting. 48 Minutes, Grape Advisory Committee Meeting, November 19, 1992, included in 1993 Annual Report, FPS collection AR-050, box 29: 48, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The discovery of leafroll in the foundation vines led to several operational changes at FPMS. The old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard was no longer used for propagation of vines for the certification program. All mother vines in mixed plantings were abandoned. The foundation vines in the Brooks blocks had been planted initially with only Registered vines. All vines in Brooks South and Brooks North testing positive for leafroll virus were removed. Foundation vines at FPMS were limited to those remaining vines in the Brooks blocks that tested negative for leafroll virus. 49 Ed Weber, Adib Rowhani, and Deborah Golino, “The Current Status of Leafroll Infections in FPMS Vineyards”, presented at the GRAPEVINE VIRUS & CERTIFICATION ISSUES FORUM, 44th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Enology and Viticulture, June 25, 1993, Sacramento, CA, FPS collection AR-050, box 34: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

As of September 1993, the only foundation grapevine material distributed by FPMS through the California R&C Program was from vines in the isolated Brooks Foundation Vineyard. That restriction reduced the number of cuttings sold in 1993-94 (49,400) by 75% over 1991-92 (200,000 cuttings). 50 FPMS Annual Report 1994, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 16, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. Pruning, training and cultivation were used in the new Brooks vineyard to eliminate overlap of canes between foundation mother vines. The foundation vineyard would be subjected to intensive future testing. 51 Minutes, FPMS Grape Subcommittee Meeting, November 16, 1993, included in 1994 FPMS Annual Report, FPS collection AR-050, box 29: 48; FPMS Newsletter, no. 13, October 1993, page 2; Memo from Susan Nelson-Kluk to CDFA, July 2, 1993, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 14, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The actual mechanism of leafroll spread throughout California vineyards by way of the mealybug vector was demonstrated in research conducted in the 1990’s by University of California scientists from Davis. A study at FPS between 1992 and 2001 revealed that four mealybug species were capable of transmitting domestic isolates of grapevine leafroll associated virus 3. 52 Golino, Deborah A., Susan T. Sim, Raymond Gill and Adib Rowhani. “California mealybugs can spread grapevine leafroll disease”, California Agriculture (November/December) 56(6): 196-201 (2002).

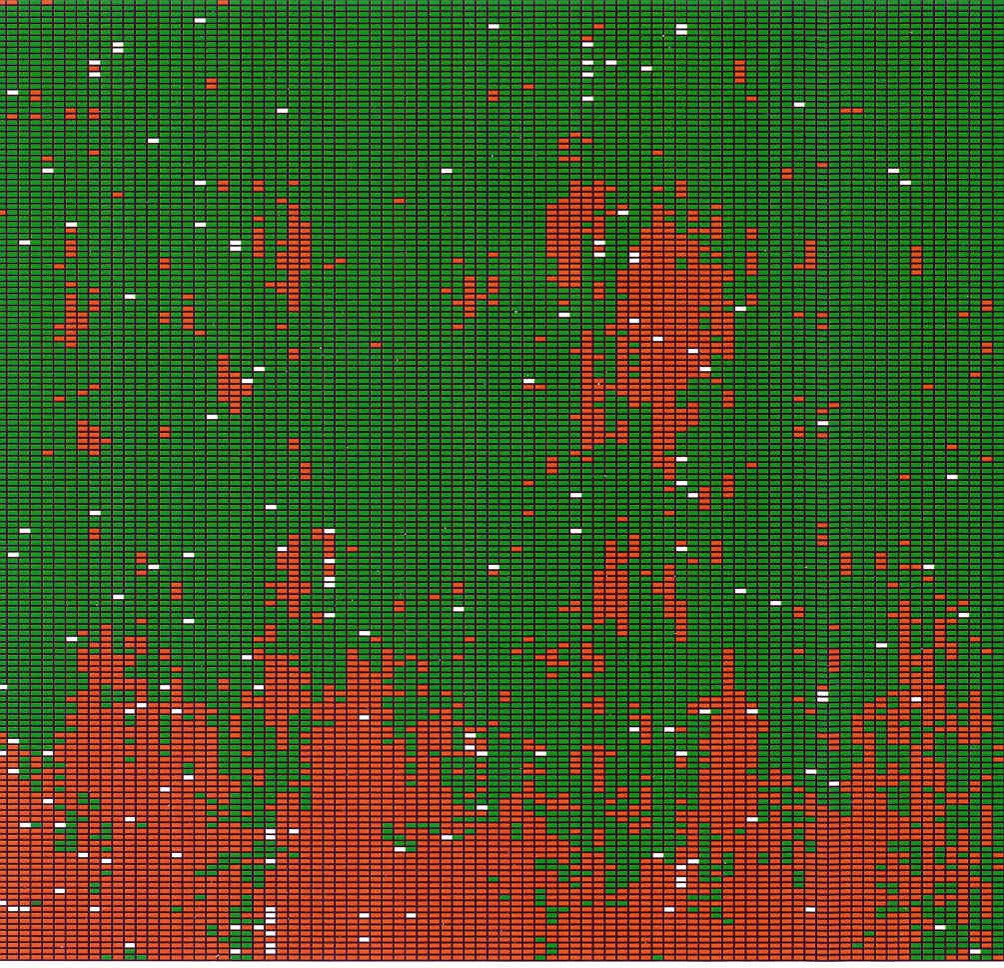

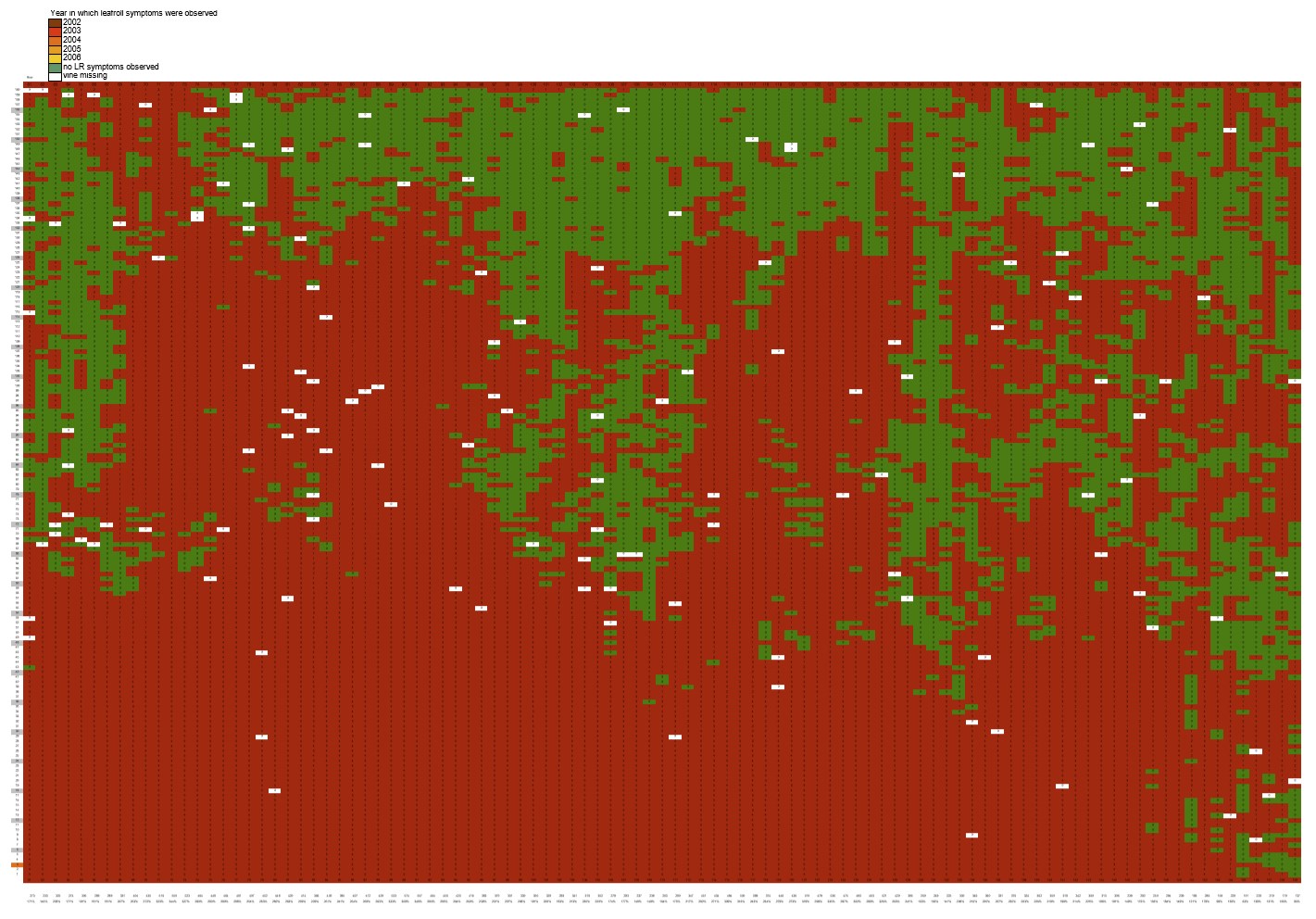

In a later study, Golino and Ed Weber, UC Extension Viticulture Farm Advisor for Napa County, mapped leafroll spread in a vineyard in Napa between 2002 and 2006. Observations were made every year. Visual observations of symptomatic vines were highly correlated with lab results showing the presence of virus in the vines, which increased over time.

Golino pointed out that colored maps (shown below) were a very visual indicator of the spread of the virus throughout the Napa vineyard over the five-year period and gave the research credence with the grape grower audience. She felt that vector studies in a lab would not have had such a strong impact. The results of the study constituted the first documentation of significant and rapid field spread of leafroll disease in a California vineyard. 53 Golino, Deborah A., Ed Weber, Susan Sim, and Adib Rowhani. “Leafroll disease is spreading rapidly in a Napa Valley vineyard”, California Agriculture 62(4): 156-160 (01 October 2008).

2002 (Leafroll in red, rating = 23.3%) |

Same vineyard in 2006 |

Rowhani adopted additional molecular tests for use in the FPMS laboratories in the 1990’s as those technologies were developed. Molecular tests screen for a range of suspected “known” viruses and virus strains using a panel of specific tests. FPMS/FPS grapevine selections became subjected to a rigorous group of tests including the more traditional biological and field index and molecular tests.

One of the newer molecular tests was polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a sophisticated and sensitive laboratory test used to detect known viruses and virus-like diseases. Reverse-transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is an extremely sensitive alternative to ELISA, providing the ability to detect viruses in woody plants throughout the year, even during periods of low titer. Primers are purchased or developed for specific viruses or a specific strain of a virus. Large numbers of samples may be run. Rowhani began using RT-PCR to test foundation vines in 1999.

|

|

PCR tests are targeted to particular viruses. One drawback of traditional molecular testing techniques such as ELISA or PCR is that they require prior knowledge of the pathogen that is the object of the test. A genetic sequence of a known pathogen (known as a primer) is applied to a sample to match the presence of that pathogen in the sample. Traditional molecular testing methods are incapable of detecting variants, such as new strains, or new unknown agents that may be present in the sample.

The new ELISA and PCR technologies were more sensitive and revealed diseases at a much earlier stage than index testing. It was not until ELISA testing for leafroll and fanleaf viruses became available in the 1980’s that FPS realized some cultivars had diseases that had gotten through indexing. The same applied to Arabis mosaic virus in the 1990’s. Field index testing does have one advantage over the more specific PCR tests: index testing is a broad-spectrum disease detector and, theoretically, reveals the presence of all diseases in the vine, whether known or not known. 54 FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, October 1999, pp. 9-10.

Golino and Rowhani were convinced that a combination of diagnostics is preferable to use of any single technique. Traditional index testing and the newer molecular based methods exhibited different strengths and were complementary to each other in terms of making a diagnosis. FPS has for years continued to employ both index and biological testing in conjunction with molecular testing. Golino and Rowhani made the decision that at least two separate tests would be required at FPMS/FPS for a selection to be determined negative for virus for the foundation vineyard.

Adib Rowhani retired as FPS Laboratory Director in 2016. His successor would develop a new cutting-edge technology for disease testing in certification programs.

Maher Al Rwahnih

Dr. Maher Al Rwahnih assumed responsibility for matters related to plant health at FPS upon the retirement of Rowhani. He was appointed Research and Diagnostic Laboratory Director at Foundation Plant Services in 2016.

Al Rwahnih works on many viral and other infectious diseases of agronomic significance to FPS crops, which include grapes, fruit and nut trees, roses, strawberries, sweet potatoes and pistachios. His research includes developing improved molecular detection methods for previously known and exotic pathogens. He also investigates the etiology of new diseases in FPS crops. Through his efforts, FPS has become a leader among agricultural test facilities in the application of cutting-edge techniques for the diagnosis and discovery of disease agents in grapevines and fruit trees.

Al Rwahnih obtained his B.S. degree in Plant Protection in 1994 from the University of Jordan, in Amman, Jordan. He earned his M.S. degree in 2000 at the International Center for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies in Bari, Italy. Al Rwahnih was awarded a PhD in 2004 in Plant Virology from the University of Bari.

Al Rwahnih developed a connection to UC Davis while studying for his Master’s degree in Italy. He took a course from visiting lecturer Jerry Uyemoto, a USDA scientist specializing in fruit tree virology who was affiliated with the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis. Uyemoto facilitated Al Rwahnih’s move to Davis.

Al Rwahnih came to UC Davis from Italy on a Postdoctoral Fellowship in 2004. He initially worked directly with Adib Rowhani in the Department of Plant Pathology in the development and optimization of detection of assays for cherry viruses. Uyemoto was also associated with the project.

After the cherry viruses project was completed, Rowhani asked Al Rwahnih to work on grape viruses and attempt to identify the causal agent of a mysterious grape disease known as “Syrah decline”. Researchers had been unable to pinpoint the cause of Syrah decline, and the symptoms were similar to those seen in multiple diseases. Al Rwahnih explored all the conventional methods for diagnosing the problem but was unable to identify a cause using those methods. He decided to “think outside the box”.

A relatively new technology called high throughput sequencing (HTS), also known as next generation sequencing (NGS) or deep sequencing, had not existed as an option for diagnosis of plant viruses when Al Rwahnih started his post-doctoral appointment in 2004. When he did the initial work on Syrah decline, the HTS technology had been used only in connection with human diseases and pharmaceuticals. There were no machines for processing HTS samples on the Davis campus at that time.

|

|

Al Rwahnih contacted the company that developed the HTS technology and inquired about using it to diagnose possible viruses in grapevines and other plants. The company offered to process four samples for plant viruses. The HTS technology proved effective in diagnosing plant viruses in grapevines. The ground-breaking research was reported in the journal Virology in 2009. 55 Al Rwahnih, M., Daubert S., Golino D. A., and Rowhani, A. “Deep sequencing analysis of RNAs from a grapevine showing Syrah decline symptoms reveals a multiple virus infection that includes a novel virus”, Virology, 387: 395–401 (2009).

High throughput sequencing is an extremely sensitive and thorough technology that gives a comprehensive picture of the entire microbial profile existing in infected vines. The HTS test compares nucleic acid sequences in a sample (such as a grapevine) to sequences known to be common to pathogens. HTS detects and reveals all markers and all diseases, whether known or not, that are in the grapevine sample. 56 Al Rwahnih et al., “Deep Sequencing analysis of RNAs from a grapevine showing Syrah decline symptoms reveals a multiple virus infection that includes a novel virus”, Virology 387: 395-401 (2009). One paper has stated that “the greatest advantage of HTS over other diagnostic approaches is that it gives a complete view of the viral phytosanitary status of a plant”. 57 Hans J. Maree, Adrian Fox, Maher Al Rwahih, Neil Boonham and Thierry Candresse. “Application of HTS for Routine Plant Virus Diagnostics: State of the Art and Challenges”, Frontiers in Plant Science, volume 9, article 1082, www.frontiersin.org, published 27 August 2018.

There are many advantages to the new technology. HTS does not require prior information on a DNA or RNA virus sequence against which to test the candidate plant. The HTS test will reveal all sequences present in the candidate plant. HTS generates millions of “reads” very rapidly. One HTS run takes about one day and can produce hundreds of millions of reads (nucleic acid sequences). The time difference for detection of pathogens can be reduced from a matter of years (with the more traditional bioassay or field index) to a matter of weeks (HTS). Grapevine material can be screened for nucleic acid sequences allowing for early detection of diseases.

One of the challenges with using HTS technology relates to its broad-brush approach to pathogen detection. HTS is sensitive in detecting previously-unknown viruses or very low asymptomatic species. The technology is very efficient in that sequences produced include all pathogens present in the plant (viruses, viroids, fungi and bacteria). Microbes of unknown pathogenicity are detected. HTS cannot reveal biological characteristics or biological importance of newly-discovered, uncharacterized nucleic acid sequences. The agronomic and viticultural significance will still have to be evaluated by observation of infected plants in order to determine the effect of the sequence on the plant. 58 Saldarelli, P., A. Giampetruzzi, H.J. Maree, and M. Al Rwahnih, “High-Throughput Sequencing: Advantages Beyond Virus Identification”, Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, eds. Baozhong Meng, Giovanni P. Martelli, Deborah A. Golino, and Marc Fuchs (Springer International Publishing, AG 2017), ch. 30, pp. 625-642.

The main goal of FPS virus testing is to identify “harmful” viruses with significant economic impact. Achieving that goal requires that scientists sort through all the sequences revealed by the HTS process to evaluate their potential impact. FPS scientists suspect that the majority of viruses identified using HTS may be background viruses that need further work to establish their biological significance.

A final challenge relates to the expense involved in using the new HTS technology. The cost per sample can be high, so the technology may be impractical for routine detection for a large number of samples.

Al Rwahnih continued his work with HTS on grapevines following the initial break-through with Syrah decline in 2009. The successes to date for HTS testing were the discovery of Grapevine red blotch virus (GRBV) and many other known and novel viruses. 59 Saldarelli, P., A. Giampetruzzi, H.J. Maree, and M. Al Rwahnih, “High-Throughput Sequencing: Advantages Beyond Virus Identification”, Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, eds. Baozhong Meng, Giovanni P. Martelli, Deborah A. Golino, and Marc Fuchs (Springer International Publishing, AG 2017), ch. 30, p. 629; Al Rwahnih, M., Golino, D., and Rowhani, A. “First report of Grapevine Pinot gris virus infecting Grapevine in the United States”. Plant Disease, 100(5): 1030 (2016). The red blotch crisis serves as an illustrative case study on how the HTS technology both identified a problem as well as added some perspective.

Red Blotch crisis

Grapevine red blotch virus (GRBV) is in the plant virus family Geminiviridae and manifests in red grape varieties by a patchy discoloration of the leaves (red blotches). The virus is more difficult to detect visually in white grape varieties. GRBV has been shown to be the causal agent of red blotch disease, which is believed to be spread by propagation of infected plant material and transmitted by a vector, the three-cornered alfalfa leafhopper. 60 G. P. Martelli, “An Overview on Grapevine Viruses, Viroids, and the Diseases They Cause”, Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, eds. Baozhong Meng, Giovanni P. Martelli, Deborah A. Golino, and Marc Fuchs (Springer International Publishing, AG 2017), Ch. 2, pp. 31, 40-41; Yepes, L.M., Cieniewicz, E., Krenz, B., McLane, H., Thompson, J.R., Perry, K.L., and Fuchs, M. “Causative Role of Grapevine Red Blotch Virus in Red Blotch Disease”, Phytopathology 108: 902-909 (2018); Bahder, B.W., Zalom, F.G., Jayanth, M. and Sudarshana, M.R. “Phylogoney of geminivirus coat protein sequences and digital PCR aid in identifying Spissistilus festinus as a vector of Grapevine red blotch-associated virus”, Phytopathology 106: 1223-1230 (2016). GRBV may alter berry ripening and chemistry and can cause significant economic harm from losses due to lower yields, quality price penalization and, ultimately, replanting costs. 61 Johann Martínez-Lüscher, Cassandra M. Plank, Luca Brillante, Monica L. Cooper, Rhonda J. Smith, Maher Al-Rwahnih, Runze Yu, Anita Oberholster, Raul Girardello, and S. Kaan Kultural. “Grapevine Red Blotch Virus May Reduce Carbon Translocation Leading to Impaired Grape Berry Ripening, J. Agric. Food Chem., XXXX, XXX, pubs.acs.org/JAFC, published February 5, 2019; Ricketts, K.D.; Gómez, M.I.; Fuchs, M.F.; Martinson, T.E.; Smith, R.J.; Cooper M.L.; Moyer, M.M.; Wise, A. “Mitigating the economic impact of grapevine red blotch: Optimizing disease management strategies in US Vineyards”, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 68(1): 127-135, ajev.2016.16009.

Red blotch disease was described for the first time on Cabernet Sauvignon vines in Napa Valley in 2008. Growers and winemakers started to observe ailing vineyards and reduced quality in the harvest and consulted scientists at UC Davis and the USDA. It would not be an exaggeration to say that a state of panic existed when the Red Blotch problem first came to public attention in California and elsewhere. At that time, there was much uncertainty as to the nature, cause and virulence of the then-unidentified pathogen.

The virus, GRBV, was identified in 2012. A public announcement of the epidemic and statement of known facts at the time were presented at the 17th meeting of the International Council for the Study of Viruses and Virus-Like Disease of the Grapevine (ICVG) at Davis in October, 2012. It is now known that Red Blotch disease is widespread in the United States in both cultivated grapes and free- living vines in riparian areas.

When the problem initially entered the public consciousness, much work was performed at several institutions researching what was thought to be a new virus, including HTS testing performed by Al Rwahnih at FPS, working with USDA-ARS scientist Dr. Mysore Sudarshana from UC Davis. They were able to closely associate the GRBV virus with Red Blotch disease symptoms using HTS. 62 Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, eds. Baozhong Meng, Giovanni P. Martelli, Deborah A. Golino, and Marc Fuchs (Springer International Publishing, AG 2017), Ch. 14, pp. 303-314, Ch. 30, pp. 629-630; Al Rwahnih, M.A. Dave, M.M. Anderson, A. Rowhani, J.K. Uyemoto, and M.R. Sudarshana. “Association of a DNA virus with grapevines affected by red blotch disease in California”, Phytopathology 103: 1069-1076 (2013a).