Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis -

October, 2018

© 2018 Regents of the University of California

The Origin of Foundation Plant Services

INTRODUCTION

Foundation Plant Services (FPS) celebrated its 50th birthday on July 1, 2008, with a luncheon attended by more than 160 stakeholders. The clean grapevine program began as a small industry-university partnership on the UC Davis campus in 1952 as a result of efforts of the Wine Institute and university scientists such as Davis Professors Harold Olmo and William Hewitt. The entity was renamed Foundation Plant Materials Service (FPMS) in 1958 and was entrusted with primary management and control of the foundation vineyards in the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program. The university center now known as Foundation Plant Services survived decades of successes and problems to become a world class facility producing and educating on healthy grapevines and other specialty crops. At the 2008 celebration, the culmination of the many FPS accomplishments was described as its founding and leadership role in the National Clean Plant Network for Grapevines (2009-2015), the goal of which is to spread the clean plant message across the nation.

The history of the FPMS/FPS clean plant work is well documented in offical paperwork and publications. The FPS Grape Program Newsletter (1971-2012) is one of the outreach efforts produced to assist and educate the industry on the value of the program. The 2008 issue spoke optimistically of the future of FPS. This chapter of the book chronicles the early challenges and growth of FPMS, and the next chapter describes how FPS built upon those efforts to become a world class clean plant center.

CALIFORNIA GRAPE CERTIFICATION ASSOCIATION (1952)

The California Grape Certification Association (CGCA) was the precursor entity to Foundation Plant Materials Service (FPMS). Dr. Curtis Alley, who served as the Manager in both programs, referred to CGCA as the "old program" and to its successor FPMS as the "new program". 1 Letter from C.J. Alley, Viticulture Specialist, FPMS, to nurseries in the 1960's, on file in FPS collection AR-50, box 25: 40, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. The goal of both programs was to develop healthy grapevine selections that were true to variety name for sale to growers as "certified" material. The primary difference between the old program and the new program was the corporate governance and management structure.

The CGCA (also referred to in the corporate documents as "Association") was organized in Fall of 1952 as a nonprofit corporation with Articles of Incorporation and Association By-Laws filed with the State of California. The Incorporating Directors included industry members L.K. Marshall of Lodi (Chairman of the Viticulture Research Committee of the Wine Institute), A.C. Huntsinger and Robert Mondavi from Napa. 2 Corporate documents filed in Olmo collection D:280, box 31: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

The University of California was a key player in the CGCA. The College of Agriculture and the California Department of Agriculture (CDA) were designated in the Articles as cooperators with industry; the "project" was approved by C.B. Hutchison, Dean of the College of Agriculture, UC Davis, as indicated in a letter to Marshall on January 31, 1952. 3 William B. Hewitt, Division of Plant Pathology, University of California, ''Certification of Grapevines as Free of Disease and True to Variety Named'', report to Wine Institute Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, March 3, 1952, filed in the Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 2, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The principal place of business of the CGCA was the Division of Viticulture building on the Davis campus. A.J. Winkler, Harold Olmo (Viticulture) and William Hewitt (Plant Pathology) represented the University at the First Annual Meeting of the CGCA on July 18, 1952. The initial set of officers elected were: Marshall, President; Mondavi, Vice President; and Winkler, Secretary Treasurer.

The CGCA by-laws provided that the management and direction would be done by 12 Directors composed of growers from around the state, two representatives from UC's Division of Viticulture and one from the Department of Plant Pathology, one from Agricultural Extension, one from the California Department of Agriculture (CDA) (renamed in 1972 as the California Department of Food & Agriculture) and one from the California Nurserymen's Association. The CGCA revenue came from dues assessments on members interested in growing certified grapevines ($1.00 per year), certification fees and contributions from interested parties. The Directors voted to request that the Wine Institute and the Wine Advisory Board be invited to cooperate and assist the CGCA with the wine and table growers.

The similarities between CGCA and FPMS related to the program goal and structure. Their common goal was production of grape material "free from disease and most nearly true to variety named". CGCA started an indexing program in 1953 on the standard commercially important wine and table varieties and rootstocks, including those that Dr. Harold Olmo retrieved from Europe in 1951. 4 C.J. Alley, ''Certified Grape Stock'', undated paper (probably around 1958-59), on file in FPS collection AR-050, box 1: 17, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. Similar program rules were defined in by-laws (CGCA) and state regulations (FPMS). Both programs included foundation and certified vines. Foundation vines were the source material tested and isolated at UC Davis. Certified vines were propagated from foundation material and multiplied, maintained and sold by nurseries and growers in the program. Both programs were in charge of quarantine screenhouses and greenhouses for imports.

The CGCA program began to evolve into FPMS at the CGCA Board meeting on November 16, 1955. The original by laws provided for the CGCA program to be self-supporting, by grants, sales of certified vines, membership dues and other contributions. By 1955, there was no income from sales of vines as the original grape material that came to the program in 1952 was still undergoing testing for virus and growing to produce wood. Previous grants had been expended. The CGCA was unable to afford the program manager's salary, which was then a half-time position. A major change in the responsibilities of the parties to the CGCA agreement was proposed at that time.

A letter from A.J. Winkler, Department of Viticulture, to Dean F. N. Briggs, Dean of the College of Agriculture, UC Davis, dated October 27, 1955, explained the situation. Winkler's letter separated the activities of the CGCA into two phases. The role of the Division/Department of Viticulture in the grape program was to ensure correct variety names for the CGCA selections, to oversee index testing of the vines for viruses, and to establish and maintain a foundation vineyard of the qualified grapevine material.

The second phase anticipated that CGCA industry members (nurserymen and growers) would establish multiplication vineyards throughout the state, maintain correct grapevine identity, obtain certification of the vines, and sell and distribute the cuttings or rootings as certified material. Winkler in his letter urged a modification of the original clean stock program by having UC assume responsibility for the activities performed in phase one by the Departments of Viticulture and Plant Pathology, as well as to assume 100% of the manager's salary. Costs for the rest of the program (the grower and nursery certification in phase two) would be assumed by the California Department of Agriculture (CDA) and the industry. 5 Minutes of the CGCA, November 16, 1955; and Letter from A.J. Winkler to Dean F.N. Briggs, dated October 27, 1955, both filed in Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

Winkler's letter and proposal were discussed at the November, 1955, CGCA Board meeting. The Board ultimately approved the restructuring of the clean plant program. An important consideration for the Board and later the University was that UC Davis had a similiar involvement with several other crops including agronomic and vegetable crops, strawberries and fruit trees. The University formally approved the restructuring.

The CDA representative at the November Board meeting offered some caveats about the new structure. Dr. G.L. Stout indicated that, prior to any CDA assumption of oversight of a grapevine certification program, state regulations would be required specifying a method for certification as well as a fee schedule. The Board requested that CDA initiate the regulatory process.

CDA held public hearings in June and July 1956 to adopt regulations for "virus free" grapevines. The resulting regulations that were ultimately adopted in two phases in September 1956 and August 1958 together provided the bones for the regulatory structure that is now the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program managed by the California Department of Food & Agriculture (CDFA). 6 California Code of Regulations, Title 3, sections 3024 et seq.; Minutes of the Board of Directors of California Grape Certification Association, Davis, California, November 16, 1955, by A.J. Winkler, Secretary-Treasurer, filed in Olmo collection D: 280, box 31: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis; C.J. Alley, “Certified Grape Stocks Available”, Wines & Vines 40(2): 28-29 (1959).

Naming the Clean Plant Program at UC Davis

The clean grapevine program at UC Davis has been known by several names over the years. The California Grape Certification Association (CGCA) was a precursor entity to Foundation Plant Materials Service at UC Davis; the university and industry were partners in that early effort. The University assumed index testing and maintenance functions for the foundation vineyard from the start under the partnership. The initial foundation vineyard was planted in 1955 and the first list of registered vines was proposed in 1956 (see below). The entity named "Foundation Plant Materials Service" (FPMS) was created at UC Davis when the regulations for the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program were formally adopted in August, 1958. The University assumed primary fiscal responsibility for the quarantine and indexing facilities and development of the foundation vineyard at that point. FPMS was the name by which the university program was known until 2003. In that year, the name "Foundation Plant Materials Service (FPMS)" was changed to "Foundation Plant Services (FPS)". The reason given was that the name "Foundation Plant Services" better reflects the FPS mission to provide a broad range of plant-related services as well as elite plant materials. Those additional services such as biological and laboratory testing, disease elimination and DNA identification services give the public access to technology developed by UC researchers to improve planting stock. Both acronyms, FPMS and FPS, will be used interchangeably in this publication, depending upon the context and time period involved.

FOUNDATION PLANT MATERIALS SERVICE (1958)

On July 1, 1958, two UC Davis programs, the virus-tested grape program (CGCA) and the virus-free cherry stock program, were officially combined and given the title "Foundation Plant Materials Service (FPMS)". FPMS was created to administer the "Grapevine and Tree Certification Program" maintaining in isolation an original supply of true-to-type plant materials tested to be free from known viruses. 7 Lynn Alley and Deborah Golino, “The Origins of the Grape Program at Foundation Plant Materials Service”, page 222, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. FPMS Club News, vol. 1 no. 1, May 1971, filed in FPS collection AR-050, box 25: 16, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. Over the years, additional crops were added at FPMS. By 2018, FPS crops included grapes, many fruit and nut trees (including cherry, olive, peach, plum, pistachio, and almond), strawberries, sweet potatoes and roses.

Governing committee

The UC administrative structure in relation to agriculture was very complicated in the early 1950's. The College of Agriculture had been reorganized in 1920 to comprise four parts: the Department of Agriculture for academic instruction leading to university degrees, the Agricultural Experiment Station for original research, the Agricultural Extension Service for public outreach, and the University Farm School at Davis. The College had its headquarters at Berkeley. The Dean of Agriculture served as the general administrative officer, but each of the four parts had its own head. 8 Ann Foley Scheuring, Science and Service, A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, ANR Publications, University of California, Oakland, CA (1995), p. 100.

In 1922, the Farm School at Davis was discontinued, and the University Farm became the "College of Agriculture, Northern branch". The University Farm was formally renamed the College of Agriculture at Davis in 1938. 9 Scheuring, supra, at p. 134. After Prohibition, the Division of Viticulture was officially moved from Berkeley to Davis. The Agricultural Experiment Station system continued to be headquartered at Berkeley.

The College of Agriculture was officially reorganized and renamed the Division of Agricultural Sciences in 1952, and the chief administrator was retitled University Dean of Agriculture. [after Dean Claude B. Hutchison retired]. Included under the umbrella of the Division in 1952 were the Colleges of Agriculture on three campuses, the Agriculture Experiment Station, the Agricultural Extension Service, and schools. Teaching programs in agriculture at the three campuses were headed by their own semi-autonomous deans, including Fred N. Briggs at Davis. The Deans reported to the head of the Division in Berkeley. 10 Scheuring, supra, at pp. 171-172. A more detailed explanation of the restructuring is contained in the chapter in this publication about the move of the viticulture program to Davis, California, around 1910.

The exact relationship of FPMS to the complicated and evolving University structure in 1957 was not explicitly defined. Austin Goheen wrote that, in its early days, FPMS was considered an independent organization within the Experiment Station at Davis. 11 A.C. Goheen, “Certification at Davis”, Department of Plant Pathology, UC Davis, January 23, 1962, filed in the FPS collection AR-050, box 33: 2, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. FPMS was administered at the outset by a committee headed by the Division of Viticulture (later the Department of Viticulture & Enology), whose Chairman served as the Chair of the committee that managed FPMS. 12 M. Andrew Walker, “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, pages 209, 213, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. Alley and Golino, 2000, supra.

It would not have been inappropriate for both the Division of Viticulture and the Experiment Station to serve as key participants in the management of FPMS, since the Division/Department of Viticulture within the College of Agriculture and the Agricultural Experiment Station had overlapping functions, interests and research issues related to grapes. Both were under the umbrella of the UC Division of Agriculture whose headquarters remained at Berkeley until 1961. Viticulture and FPMS employees performed the index testing, planting of vines in the foundation vineyard at UC Davis and distribution of grapevine material from campus vineyards. Other departments with representation on the FPMS administrative committee included Pomology (for cherries), Environmental Horticulture, and Plant Pathology.

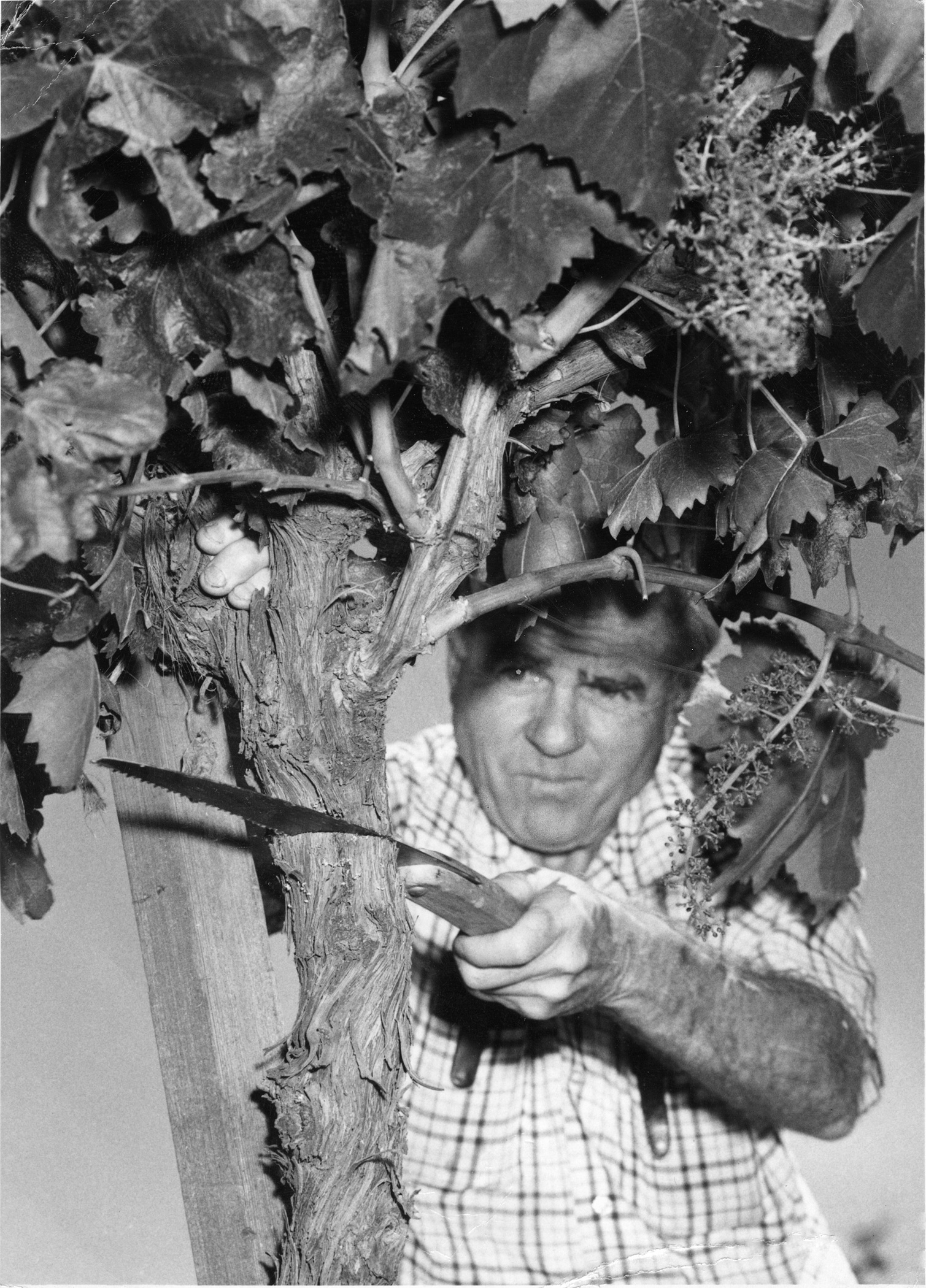

Manager of CGCA/FPMS

Dr. Curtis Alley served for twenty years as the first Manager of the clean grape program at UC Davis. He had attended UC Davis and obtained his PhD in Genetics in 1951 studying with Harold Olmo. Alley then worked in commercial peach breeding in Red Bluff for one year. The CGCA Board of Directors voted to hire him as Manager of their new grape program at a meeting on December 29, 1952. The position was a half time one at that time, so Alley also worked half time as a junior specialist in the Experiment Station at UC Davis. 13 FPMS Club News, vol. 1, no. 1, May 1971, FPS collection AR-050, box 25: 16, Department of Special Collections, University of California, Davis.

In 1957, the University agreed to manage FPMS and assumed 100% of the salary of the Manager of the clean plant program at the Staff Research Associate level. However, FPMS could not afford a full-time manager during Alley's tenure, so he continued half time at FPMS and half as a viticulturist in the Experiment Station. 14 FPMS Club News, May 1971, p. 4 supra. Alley served as Manager of FPMS until 1971, when he left to do research full time in the Department of Viticulture & Enology with Cornelius Ough (grapevine propagation, grape variety-region adaptability, clonal selection and evaluation). 15 Letter from Curtis Alley to James Lider, Farm Advisor, Napa, dated June 13, 1972; Minutes of Meeting, California Grape Certification Association, December 29, 1952, Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 8; see also Walker, ASEV, 2000, p.213; Harold P. Olmo, Plant Genetics and New Grape Varieties, California Wine Oral History Project, Regional Oral History Office, University of California/Berkeley, interview conducted by Ruth Teiser, Regents of the University of California, 1976, pages 85-86.

There was a steep learning curve in the early years of the FPMS clean plant program. Scientists and staff were consumed with research and development activities for virus detection and treatment and development of the foundation vineyards. Plant pathologists settled on reliable indicator vines for the indexing process and developed heat treatment therapy for disease elimination. FPMS was eventually able to provide a healthier (heat treated) grapevine product called "superclones" to grape nurseries and growers by the early 1970's.

Grapevine material came to the new clean stock program at UC Davis from foreign and domestic (within the United States) sources. Effective clean plant programs involve governmental overseers willing to enforce established standards. Congress, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the California Legislature and State Department of Agriculture (CDA) were all motivated to protect the influential grape and wine industry within their jurisdictions. Although all grapevine material that is submitted to the UC Davis program is required to meet specific standards established by the California regulations, foreign grapevine imports are subject to special scrutiny and are held in quarantine isolation until they meet federal requirements for release to certification programs.

FOREIGN GRAPE SELECTIONS

Olmo travelled the world to collect grape germplasm that he believed would satisfy the industry demand for better varieties and clones. Importing grapevine material to the United States in the early years of the program had its challenges. National law and regulations had recently been enacted putting restrictions on Vitis imports from Europe for the protection of the grape industry in the United States. The clean plant program at Davis became a cooperator with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and California Department of Agriculture (CDA) (renamed the California Department of Food & Agriculture in 1972) to implement the new rules.

Historically grape germplasm had been moved from its center of origin or center of collection to new areas of the world without regard to diseases or pests that might be present in the materials. Sometimes disasters resulted, such as grape phylloxera to France and fanleaf virus to North America. 16 Alley and Golino, ASEV, 2000, page 226. Diseased grapevine material was imported to the United States for at least 100 years without restriction until 1948.

Uncontrolled importation of grape plant materials into the United States was ended in December 1948 by way of federal regulations known as "Quarantine 37". 17 13 Federal Regulations sections 319.37 to 319.37-25, contained in Federal Nursery Stock, Seed and Plant Quarantine No. 37. The regulations were enacted under the authority conferred by the Plant Quarantine Act of 1912 (7 USC § 160) to prevent the introduction into the country of certain plant and fruit diseases either new to or not prevalent in the United States. Importation of Vitis spp. (grapevine) from Europe was specifically prohibited, citing vine mosaic virus. The USDA could allow exceptions to the general rule and approve imports under special conditions (scientific or educational purposes) or with a USDA Departmental permit. 18 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 7, Section 319.37-2; A.C. Goheen, Department of Plant Pathology, UC Davis, ''Importation of Grapevines into California through Quarantine'', unpublished paper dated February 5, 1970. Any grapevine material that entered with a permit was quarantined post entry until it was determined by plant pathologists that it did not suffer from certain diseases, including viruses. 19 Golino D.A., M. Fuchs, M. Al Rwahnih, K. Farrar, A. Schmidt and G.P. Martelli, “Regulatory Aspects of Grape Viruses and Virus Diseases: Certification, Quarantine, and Harmonization”, Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, eds. B. Meng, G.P. Martelli, D.A. Golino, and M. Fuchs (Springer International Publishing AG 2017), pp. 581-597.

1947

Olmo was a plant explorer for other crops in addition to grapevines and travelled on sabbatical leave to Europe and the Middle East in 1948 and 1949 to acquire new varieties for various crops. In 1947, he requested in advance of that trip a Departmental permit from the USDA to be issued to the U.C. Davis College of Agriculture "as a whole to take care of the ordinary needs of the College's various departments". The result was USDA Special Permit No. 42665, issued on December 10, 1947, in accordance with Regulation 14 of Quarantine No. 37 to the University of California, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Davis, California. The permit was valid indefinitely ("until revoked"). One of the attachments to the permit indicated that "permits do not authorize the importation of grape (Vitis spp.) from European sources". 20 The following documents can be found in Shields Library, UC Davis, in the Department of Special Collections, D-280 (Olmo), box 100: United States Department of Agriculture, Import Permit No. 42665, issued December 10, 1947; Letter from George Becker, Import and Permit Section, USDA, to Purchasing Agent, University of California, College of Agriculture, Davis, dated December 12, 1947; Letter George Becker to Harold Olmo, dated December 12, 1947. See also, Code of Federal Regulations, 1949 edition, Title 7, Part 319, sections 319.37 to 319.37-25.

Olmo used the Special Permit to import grapes in 1948-49. In April 1948, CDA clarified to A.J. Winkler the procedure by which grape material could be imported to California using the Special Permit. H.M. Armitage, Chief, California Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine wrote that the USDA (Bureau of Plant Quarantine) had reached an agreement with the California Department of Agriculture (Bureau of Plant Quarantine) on the conditions for importing grape material into California. Generally, permits would be denied for direct importations of grape plants and cuttings into California from all countries due to possible virus issues. However, in the case of official agencies such as the University, an exception was approved under the following conditions: (1) imported grapevine material was retained under federal jurisdiction in Washington D.C. for one full growing season to permit observation "and elimination" of any visible disease found present; (2) subsequent retention in quarantine at Davis until released by the State Department of Agriculture; and (3) ultimate rejection or release to be based on findings during the retention period. 21 Letter from H.M. Armitage, Chief, Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, Department of Agriculture, State of California, to Dr. A.J. Winkler, Division of Viticulture, Agricultural Experiment Station, College of Agriculture, University of California, Davis, dated April 6, 1948, filed in Olmo collection D-280, box 100: 4, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

Later correspondence between Olmo and the USDA showed that Olmo sought to import grapes using Special Permit No. 42665. 22 Letter from B.Y. Morrison, Division of Plant Exploration and Introduction, ARS, USDA, to H.P. Olmo, dated May 21, 1948, and Letter from George Becker, Import and Permit Section, ARS, USDA, dated June 30, 1948, both located at Olmo collection D-280, box 100: 2, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. Entries in the Olmo importation records maintained at FPS indicate that he sent grape varieties from Afghanistan and Greece during his 1948 exploration trip.

Post-entry quarantine in the late 1940's and early 1950's amounted to growing vines out in a greenhouse for two years and inspecting them for symptoms of disease. In 1950, no one knew how to make reliable tests for grape viruses. Once the new quarantine regulations were adopted, the USDA quarantine greenhouses in Glenn Dale, Maryland, were soon filled to overflowing with rooted grape cuttings. 23 A.C. Goheen, Research Plant Pathologist, “Grape Quarantine in the United States”, dated January 16, 1986, on file FPS collection AR-050, box 28: 6, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. Many precious vines died. Grapes are not easy to maintain in greenhouses and the Eastern climate was not favorable for growing Vitis vinifera (the European grapevine varieties). These difficulties meant that a virtual embargo existed on the introduction of new grape clones. 24 Alley and Golino, ASEV, 2000, page 227.

1952

The Division/Department of Viticulture and Department of Plant Pathology collaborated on an ongoing basis regarding virus indexing work from the time the grape imports first came to UC Davis. Plant pathologist Dr. William Hewitt worked closely with Viticulture staff during the initial years, as no one in Viticulture had those qualifications. It was believed that Olmo had "held" the Special Import Permit for the years prior to 1951 as he was the one who initially proposed the program to the USDA. 25 The National Grapevine Importation Program at FPS; Interview with Susan Nelson-Kluk, Manager, FPS Grape Program, July 21, 2014. The pre-1951 imports had come to the United States to USDA facilities in Maryland and then on to Davis after the quarantine release process.

The process changed with the grape imports collected by Olmo in Europe in 1951. Olmo was able to send back 48 potentially superior clonal selections from Spain, France, Switzerland and Germany. The grape and wine industry intervened to overcome regulatory issues for those selections. While Olmo was away, the Wine Institute in California obtained permission from the USDA and CDA for the cuttings to be flown directly to Davis for quarantine, instead of having first to go through the two-year process in Maryland. The university and industry cooperators argued that a greater percentage of imported cuttings would survive in California, and the cuttings could be indexed while in quarantine in California, making them available to California grape growers a year earlier.

Hewitt received the foreign introductions sent directly to Davis in 1951 because he was a plant pathologist as required by Quarantine 37. Viticulture and enology researchers at UC Davis approached the USDA and were issued a "Special Departmental Permit" for grapes that allowed the first grape quarantine facilities to be built at UC Davis in 1952. 26 The National Grapevine Importation Program at Foundation Plant Services, University of California, Davis, revised March 2008, page 1; brochure on file at FPS.

Staff and facilities for grape quarantine activities at UC Davis were initially provided by the Division/Department of Viticulture from 1951 until 1957, when Albert Winkler (Chair, Department of Viticulture) retired. The quarantine houses operated under index regulations prescribed by the California Bureau of Plant Quarantine. 27 Memo to D.H. Scott, Plant Industry Station, Small Fruits and Vine Section, Beltsville, MD from A.C. Goheen, Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Davis, dated March 14, 1958, FPS collection AR-050, box 28: 40, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. A screened quarantine greenhouse funded by the Wine Advisory Board (Wine Institute) was erected on the UC Davis campus in March 1952 to function "somewhat" as a substation of the USDA quarantine house in Maryland. Olmo's European clones were potted up in the screenhouses in 1952. An additional screened house for indexing work was annexed to the original structure in 1953. The screenhouses were isolated about a mile from the nearest vineyard planting on Armstrong tract in area B2 on the Davis campus. 28 Curtis Alley, Olmo collection D-280, box 19: 9-11, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; William B. Hewitt, Division of Plant Pathology, University of California, ''Certification of Grapevines as Free of Disease and True to Variety Named'', report to Wine Institute Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, March 3, 1952; H.P. Olmo, Professor of Viticulture, University of California, ''The California Grape Certification Association'', OIV Bulletin 278 (287): 11-20 (1955).

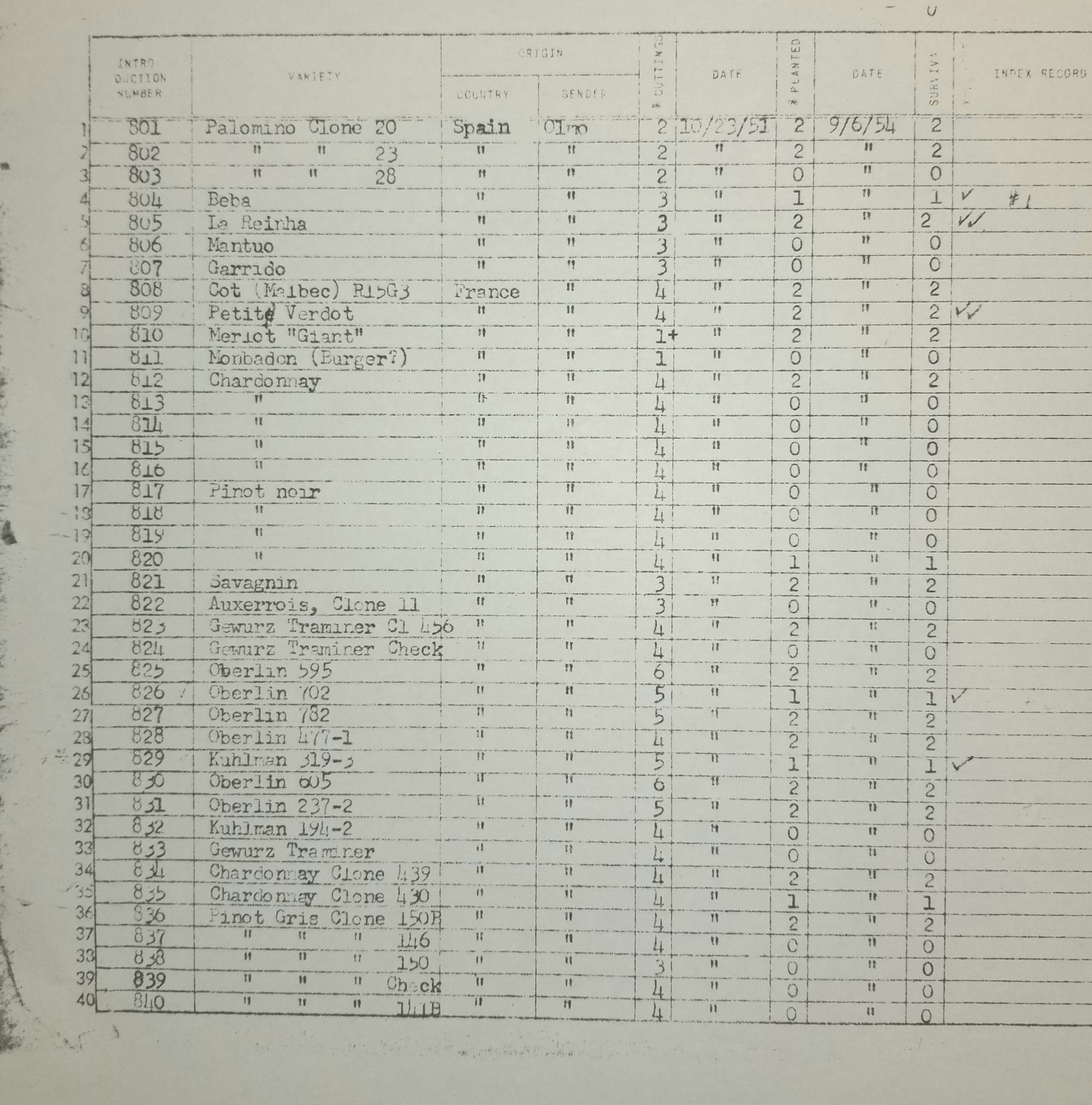

Two large binders at FPS contain the records of the grape introductions that were imported directly to Davis under the aegis of William Hewitt. The first binder is labelled "Grape Q House, import numbers 805-1305, Hewit's [sic.] Introductions" and contains grape importations from 1951-1964. The initial 40 entries show 40 clones sent by Olmo from France and Spain in 1951, including traditional winegrape varieties such as Chardonnay, Malbec, Petit Verdot, Pinot noir, Gewurz Traminer [sic.], Pinot gris and Palomino.

The binder also notes the subsequent index history for each clone and testing results. Many of the importations either died or were discarded. Unfortunately, the primitive metal screen on the quarantine screenhouse was so fine-meshed as to be opaque, and many of the valuable vines perished in the first Davis quarantine house. An extreme hot spell in the summer of 1956 in Davis also contributed to the death of many vines. 29 Alley and Golino, ASEV, 2000, page 227; C.J. Alley, “California Grape Certification Association”, January 14, 1957, FPS collection AR-050, box 19, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The second Hewitt binder contains introductions 1306 through 2116 and covers the period 1965-1969.

The 800 numbers were assigned at FPS as Introduction numbers for the Davis facility.

1956, the Departmental Permit

A formal arrangement regarding Hewitt's role in grape importations was made in 1956, around the time that the university assumed management of the CGCA program. The USDA Plant Introduction Office entered into a cooperative research agreement with the Agricultural Experiment Station at Davis in 1956 to study grape viruses and relieve pressure on the USDA facilities in Maryland. The USDA issued a "Departmental Permit" to William Hewitt, Department of Plant Pathology, so that the rooted grape cuttings from Glenn Dale, Maryland, could be transferred to Davis and retested under the post-entry quarantine in California. 30 A.C. Goheen, Research Plant Pathologist, ''Grape Quarantines in the United States'', January 16, 1986, on file in FPS collection AR-050, box 28: 6, Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. 31 A.C. Goheen, “Importation of Grapevines into California through Quarantine”, unpublished paper dated February 5, 1970, on file at FPS.

The USDA's original concept for the "Departmental Permit" was to allow for movement of a limited amount of plant material (10 sticks or less) for research purposes. The Departmental Permit was originally intended for USDA use only. The permit was tied to a person (usually a plant pathologist) at a certain institution to ensure accountability and responsibility in that person, rather than to an institution in general.

The Departmental Permit was gradually modified over time by practice. The USDA allowed a greater and greater number of plant sticks to be moved over time. Gradually, permission for the "movement of sticks" was expanded from USDA personnel to include entities such as universities and such activities as qualification of imported material for certification programs through disease-testing regulations. Post-entry quarantine testing and treatment was allowed at various universities, including UC Davis.

The Department of Plant Pathology initially accepted primary responsibility for post-entry quarantine testing at UC Davis on the basis that the quarantine testing was a research function to study possible new viruses accompanying the imports and to protect the California grape industry. The indexing was funded by Department research funds. 32 A.C. Goheen, Importation of Grapevines into California, 1970, supra. Hewitt was joined in that effort by USDA scientist Austin Goheen in 1956. 33 Memo to D.H. Scott, Plant Industry Station, Small Fruits and Vine Section, Beltsville, MD from A.C. Goheen, Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Davis, dated March 14, 1958, FPS collection AR-050, box 28: 40, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. In March 1958, J.B. Kendrick, Professor of Plant Pathology, notified the California Bureau of Plant Quarantine that the facilities and duties associated with grape quarantine imports and index testing at UC Davis had been transferred from Viticulture to Plant Pathology under Hewitt and Goheen. 34 Letter to A.P. Messenger, Bureau of Plant Quarantine, Department of Agriculture, from J.B. Kendrick, Sr., Professor of Plant Pathology, UC Davis, dated March 13, 1958, FPS collection AR-050, box 28: 40, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The Bureau of Plant Quarantine agreed and centered administrative responsibility on Hewitt, requiring requests for new material to be made through him.

Indexing at the quarantine facility at UC Davis had amassed a large backlog of importations by 1964 due to limited facilities and limited help. At the time, the maximum capacity of the Davis quarantine house was 25 clones per year. James Cook, Chairman, Department of Viticulture & Enology, complained to the USDA New Crops Research Branch that, as result of the backlog, foreign grape importations suffered a "paralyzing embargo" because the UC plant pathologists restricted imports until the backlog could be tested. Cook proposed that the USDA approve the small station in Chico as a post-entry quarantine area, where foreign introductions could be planted, fruited, observed and indexed. 35 Letter from James A. Cook, Chairman, Department of Viticulture & Enology, to L.C. Cochran, Head, New Crops Research Branch, USDA, dated October 22, 1965, located in the Olmo collection D-280, box 100: 6, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The 29-acre state forestry station at Chico had been transferred from the Board of Forestry to the University's Department of Agriculture in 1893. The site was formerly part of Rancho Chico owned by John Bidwell. The Chico station was a local station that had previously been assigned to tree crops. 36 Ann Foley Scheuring, Science & Service: A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California (Regents of the University of California, Division of Agriculture & Natural Resources, Oakland, CA, 1995), page 41. The USDA-ARS revised the program to permit UC Davis to grow index-indicator plants in gardens at Chico for a period of four years while the introductions were held in quarantine at Davis. The first plantings under this plan were made on some 80 clones in 1965, followed by 295 clones in 1966 and 250 clones in 1967. Hewitt foresaw that imports might begin again in 1968 because of the relief provided by the Chico indexing. 37 Letter to Harold F. Winters, New Crops Research Branch, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD, from Wm. B. Hewitt, Professor Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Davis, dated May 17, 1966, on file at Foundation Plant Services. Hewitt's import binder number 2 shows regular introductions resuming at Davis in 1968.

1969

William Hewitt moved from Davis to Reedley in 1969 to serve as the Station Superintendent at the University of California's Kearney Agricultural Center. By 1970, the Department of Plant Pathology was satisfied that grape imports were bringing no new viruses to California and no longer considered the quarantine index testing to be a research function but rather a service function. 38 A.C. Goheen, Importation of Grapevines into California, 1970, supra; FPMS Club News, vol. 1 no.1, May 1971, FPS collection AR-050 25: 16, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The reasoning of the Department illustrated a dilemma encountered by some scientists working at UC Davis of "commitment to two masters" - the basic sciences and the agricultural industry. "Land-grant colleges of agriculture had continually to keep in mind the twin goals of discovery and service, finding as they could a balance between the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake and the pursuit of solutions to client problems". 39 Scheuring, supra, at p. 119. The work at FPMS was to be viewed by the University as "service work" - testing and treating candidate vines for qualification in the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program and maintaining foundation plant material for use by the industry. That conclusion had perceived negative implications for University scientists in the FPMS program, as research work was preferred by the University for professional advancement purposes.

The USDA Departmental Permit was transferred from Hewitt to USDA Plant Pathologist Austin Goheen, who began importations in 1969 and continued to oversee FPMS indexing procedures until his retirement in 1986. In 1988, FPMS ceased making commitments to import additional grape materials due to the loss of equipment and facilities associated with Goheen's retirement. No importation occurred at FPMS between 1988 and 1993. Potential clients were referred to the two remaining North American quarantine facilities at Geneva, New York, and Saanichton, British Columbia. 40 Alley and Golino, ASEV 2000, supra, at p. 227. For a time in the 1980's, other grape facilities associated with universities were granted limited permission to process imports, including David Cameron at OSU in the 1980's and scientists at Missouri State University.

Vine importation and quarantine activity actively resumed in 1993 after the USDA issued a new Departmental Permit to FPMS in 1991-92. FPS Director, Deborah Golino, was authorized to administer the new permit. A new physical facility for processing grape imports as well as domestic accessions was funded by a federal grant and completed in 1994. The resumption of importations and the then-new FPMS facilities are discussed in greater detail in Part 2 of the story of Foundation Plant Services.

FOUNDATION VINEYARDS AT UC DAVIS

The heart of the clean plant program is the foundation vineyard. That collection of healthy vines is regularly tested and inspected and serves as the source of certified material for the grape and wine industry. The initial foundation vineyard for the California R&C Program was planted on the UC Davis campus in 1955. The founders of the clean plant program contemplated that the vineyard be isolated and planted in clean land. The original rules of the California program specified that the planting be on land which had not been planted to grapes for at least 10 years. The regulations also required that the land be isolated at least 150 (later 100) feet from non-indexed vines. 41 Memo from Curtis J. Alley, Manager CGCA to Board Members, CGCA, July 16, 1956, Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 3, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The foundation vineyards at FPS in 2018 contain most of the commercially-important grape varieties and clones from all over the world. Some of the heritage material came to California in the 19th century and was incorporated into University Experiment Station vineyards as well as the Department of Viticulture variety collection planted at Davis beginning in 1913. In the 1990's, FPMS increased efforts to collect California heritage clones. Other grape varieties were later acquired by FPS through exchange agreements with grape centers in countries such as Spain, France, Portugal, Croatia and Greece. Breeder selections from UC Davis and other important grape centers in the United States are represented in the foundation vineyard. This publication is meant to give the history of the varieties and selections in the FPS foundation vineyards.

The foundation vineyards at UC Davis have undergone several iterations between 1955 and 2018. Improvements in disease detection and disease-elimination treatment, as well as the increasingly large size of the FPS foundation grapevine collection, have been the impetus for moving to successive foundation vineyard plantings. The history of the foundation vineyards at FPS provides valuable context for the discussion on the evolution of FPS.

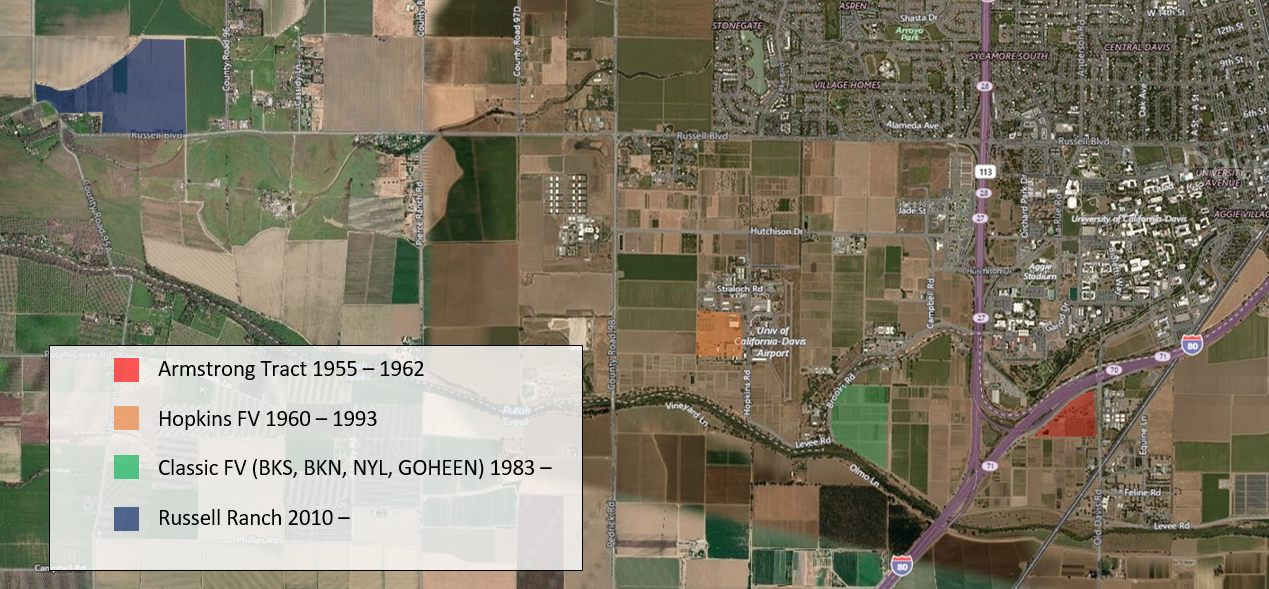

Armstrong Foundation Vineyard, "Block A" (1955)

Grapevine material entering the CGCA/FPMS program in the 1950's was indexed in pots in a screenhouse on the UC Davis campus. The CGCA Board of Directors was concerned in 1953 about possible virus transmission in the soil and agreed that they should not install foundation plantings until the index process showed the vines then undergoing testing were free of virus. They knew that the delay would mean the industry could not get registered material for four to six years for planting in certified increase blocks. The Board agreed that material could be distributed in the interim but not as certified wood. 42 Minutes of the California Grapevine Certification Association, March 31, 1953, Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

On December 9, 1954, the Board voted that the foundation vineyard at UC Davis be limited to a few vines of each of the commercial varieties and rootstocks and that multiplication to produce sufficient wood for a reasonable number of certified vineyards be undertaken immediately on University land. 43 Minutes of the California Grapevine Certification Association, December 9, 1954, Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The land identified as suitable for the first foundation vineyard had been first leased (1917) and then purchased (1931) by the University south of the Davis campus. The 300-acre property was known as the Armstrong Ranch and was later referred to as Armstrong Tract. 44 Scheuring, supra, at p. 70, citing the University of California Chronicle 9-19 (1907-1917) and materials on file in the Department of Special Collections at Shields Library, UC Davis.

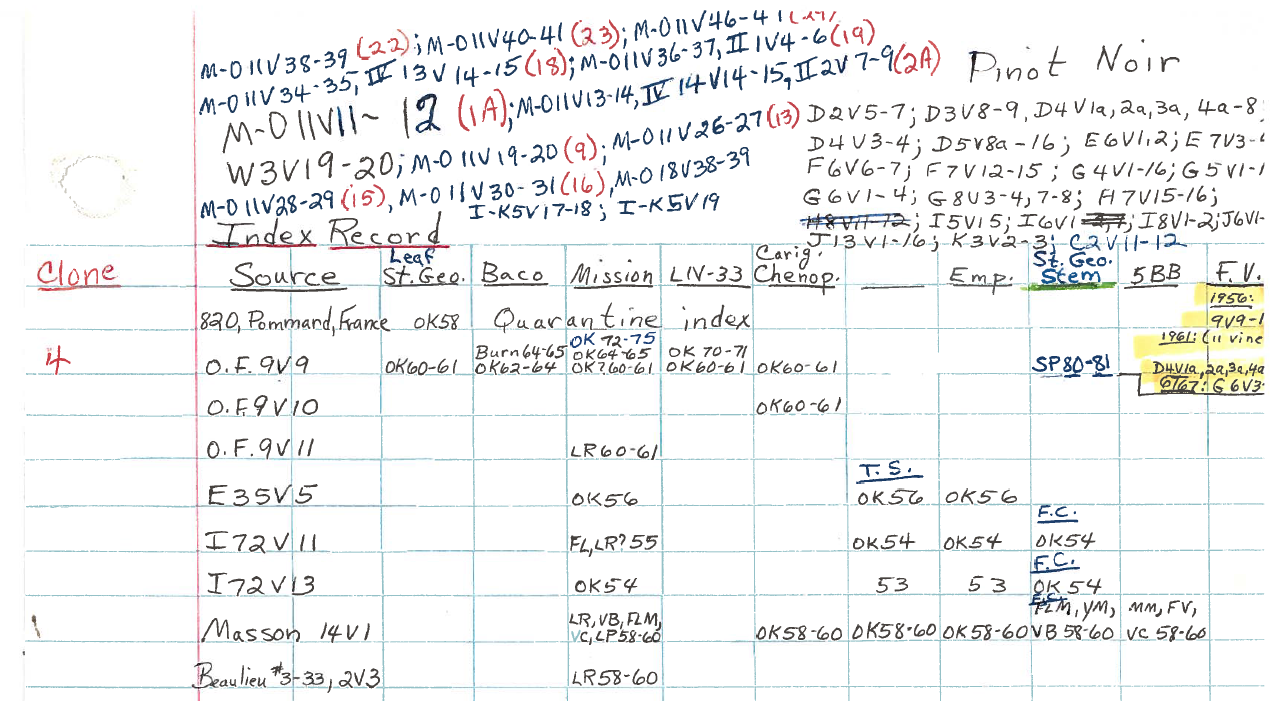

The vines in the first UC Davis foundation vineyard were planted in March, 1955. That 4-acre foundation vineyard was located in the Armstrong Tract and described as "at the intersection of S.P. Railroad and U.S. 40 [Highway 99] in old Agronomy Field". The foundation vineyard was designated "Block A". The initials "O.F." used in Austin Goheen's indexing binders at FPMS to refer to plantings in Block A stand for "Old Foundation".

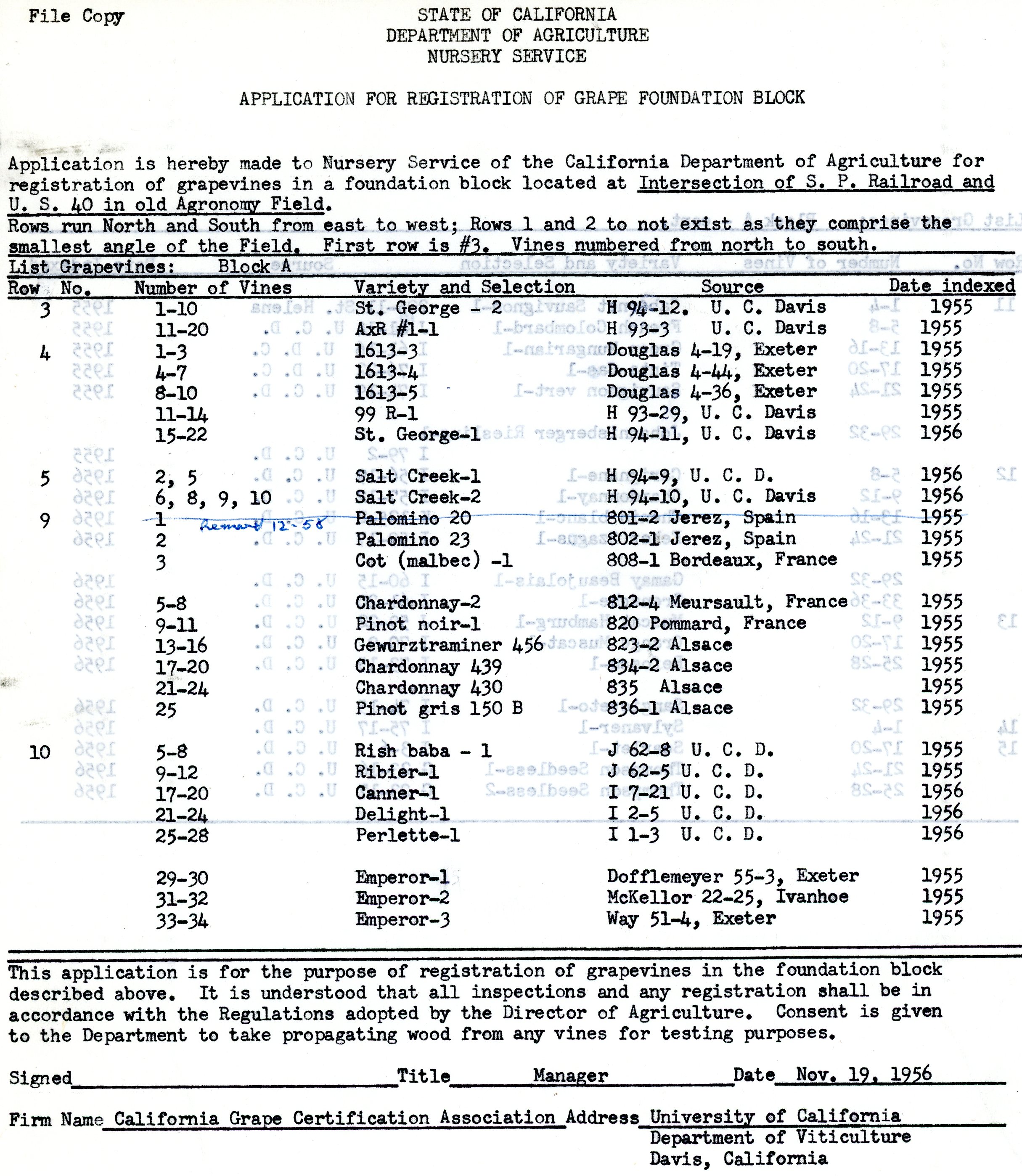

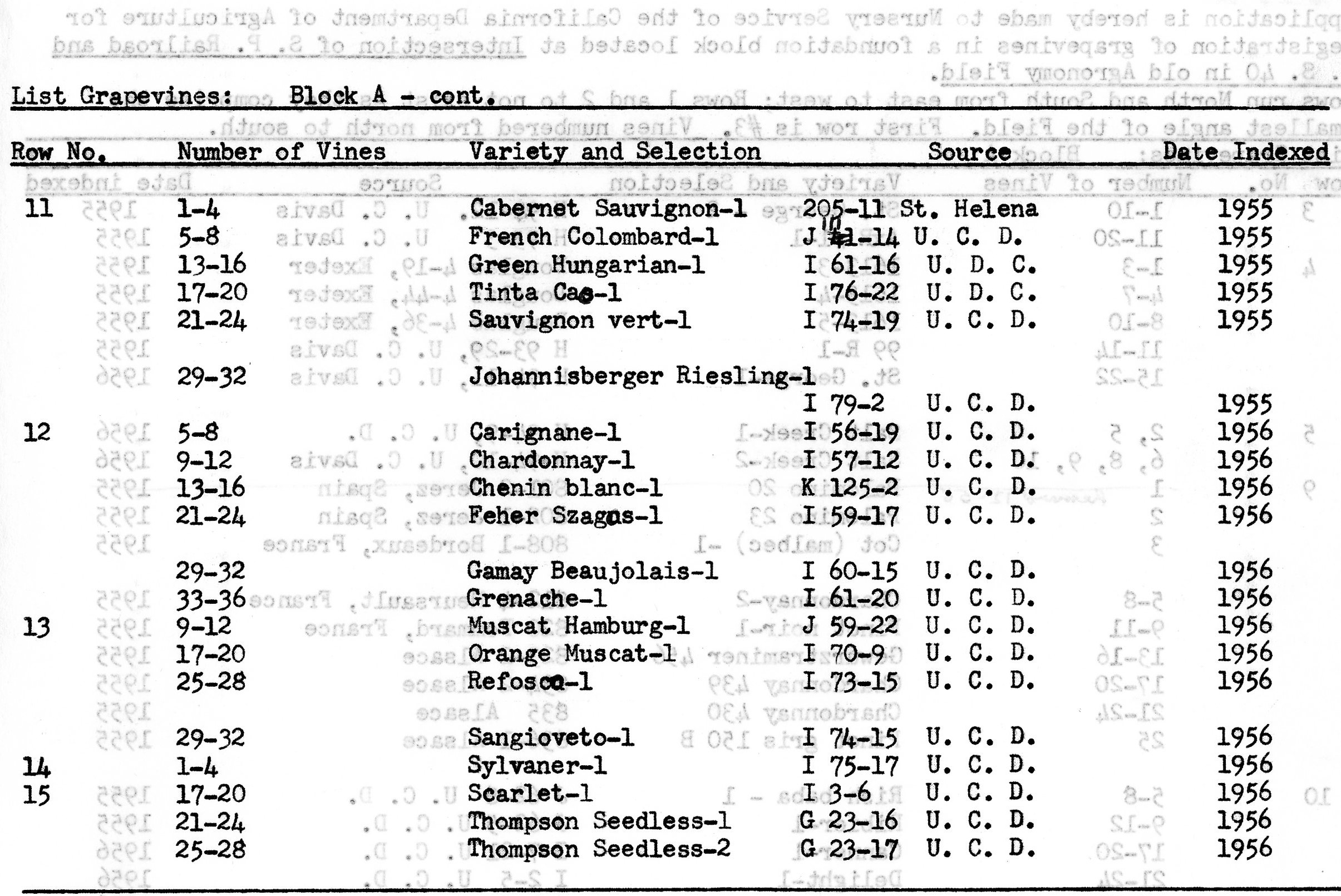

The first proposed list of Registered vines from Block A was submitted to the then-California Department of Agriculture (CDA) in 1956. A "Registered vine" was a grapevine that tested negative for viruses at issue and was identified as true to variety. Registered foundation vines served as the source material for the varieties and clones ultimately released to nurseries and commercial growers in the certification program. The initial list in 1956 showed nine rootstock selections (5 varieties), 10 table and raisin grape selections (7 varieties) and 27 winegrape selections (23 varieties). 45 Application for Registration of Grape Foundation Block, by California Grape Certification Association, Department of Viticulture, University of California, Davis, to Nursery Service, Department of Agriculture, State of California, dated November 19, 1956. The list showed the following:

In the early years of the clean plant program at UC Davis, FPMS managed "an increase block" on campus, comprising about 8 acres, which was used to multiply the commercially important rootstock and scion varieties. 46 ''Foundation Plant Materials Service'', unpublished paper on file in FPS collection AR-050, box 1: 17, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The multiplication block was located in Blocks V, W and X of the Department of Viticulture vineyard at Armstrong Tract. 47 “Proposed Budget for Foundation Plant Materials Services”, ~1956-57, at page 6; on file in FPS collection AR-050, box 1: 17, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The distribution cards for 1956-1962 on file at FPS show customer orders for winegrape cuttings from that "multiplication block". FPMS also maintained an adjacent one-half acre for planting of a certified nursery.

In 1956, the first indexed wood from the new foundation vineyard was released for multiplication to cooperating nurseries and growers who had the isolated plots and clean land required to participate in the California certification program. 48 Curtis J. Alley, “Development of Virus-Free Grape Varieties”, Wines & Vines, (February, 1964), pages 22-23. Newly indexed varieties were subsequently added to the program and became available for multiplication in years following. 49 Letter from Curtis Alley to participating nurseries, dated January 2, 1958, FPS collection AR-050, box 25: 40 (1958 distribution), Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

Certified grapevine stock sourced from the UC Davis foundation vineyard first became available to the public in winter 1959 from nurseries and growers, who were referred to as "[R & C] program participants". Program participants offered "certified stock" for sale from their increase blocks, which were the blocks used commercially by the nurseries and growers to multiply the registered material into many copies. "Certified stock" were vines, rootings, cuttings, buds or plants propagated from foundation/registered material and maintained by participants pursuant to program rules. The initial six cooperators that offered the first certified wood developed in the CGCA/FPMS program were: California Nursery Co. in Niles; Deer Creek Nursery Co. in Los Molinos; DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation in Delano; Leroy Anderson in Snelling; Rancho Fortuna in McFarland; and Stribling's Nurseries in Merced. 50 C.J. Alley, ''Certified Grape Stocks Available'', Wines & Vines 40(2): 28-29 (1959).

Once the certified material became available to the public through the commercial nurseries, the University cut back on its own multiplication/increase blocks on campus and maintained only an initial start of each scion variety and rootstock in the foundation vineyard. FPMS was not equipped to participate in increasing the numbers of all the varieties and rootstocks that qualified for the foundation vineyard. 51 “Foundation Plant Materials Service”, unpublished paper on file in FPS collection AR-050, box 1: 17, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

UC Davis developed more sensitive indicators for the detection of virus by 1960. The older registered grape plantings in Block A were found to be infected with strains of grapevine leafroll virus, the effects of which were poorly understood at the time. The program regulations were amended in May 1961 to permit distribution from the vines in Block A that had not yet tested leafroll positive because those vines were "free of all virus diseases other than leafroll". FPMS staff planned to replace the leafroll-infected vines as rapidly as possible with leafroll-negative selections for planting in the future foundation vineyard at Hopkins Road. 52 Austin Goheen, “Certification at Davis”, Department of Plant Pathology, UC Davis, January 23, 1962, FPS collection AR-050, box 33: 2; Minutes of the Committee Meeting of Foundation Plant Materials Service, November 22, 1961, p. 4, FPS collection AR-050, box 1: 19, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The portion of the original foundation vineyard (Block A) which included scions and rootstocks in quantities of four vines (scions) or ten vines (rootstocks) was reduced in classification to a mother block. The remainder of the planting was removed from the certification program. Once all of the varieties and selections remaining in that recharacterized mother block were established in the new Hopkins Foundation Vineyard, the mother block was phased out of the program. 53 Curtis Alley, “Foundation Plant Materials Service – Grape Registration & Certification Program”, November 6, 1963, Olmo collection D-280, box 19: 10-11, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

Hopkins Road Foundation Vineyard (1960)

A new FPMS foundation vineyard was planted on the UC Davis campus west of Hopkins Road beginning in 1960 after better virus indicators improved disease detection and plant selection. Hopkins Road and Hopkins Tract were named after the Hopkins family who had owned the property. The first varieties were distributed to program participants from the new foundation vineyard in 1963. 54 C.J. Alley, A.C. Goheen, and W.B. Hewitt, “Indexed Grape Varieties for Spring Planting 1963”, December 1962, FPS Collection AR-050, box 1: 19, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. At that time, there were 6 rootstock varieties, 16 table and raisin grapes and 40 winegrape varieties in the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. 55 Curtis J. Alley, ''Development of Virus-Free Grape Varieties'', reprinted from Wines & Vines, February (1964), on file Olmo collection D-280, box 59: 24, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

Olmo numbering system for vineyards

The Armstrong (Block A) and Hopkins Foundation Vineyards at UC Davis were numbered using a system created by Harold Olmo. He numbered the Davis vineyards using alphabetical letters for blocks and numbering of rows within the blocks. Olmo explained the origin of that system when he sat in 1973 for an oral history of his career at the University:

"When I came to the department [Viticulture, 1935] I was a little flabbergasted at the lack of orderliness in keeping collections of materials and so on, and really having, say, vineyard blocks that were well outlined and were done on a more or less geometric pattern."

"I remember during my years as a graduate student at Davis, when I was working as a research assistant, two of my best friends at the time on the staff were Dr. William Mersman [mathematics] and Dr. Willard Berggren [physics]. They, of course, knew about surveying so I talked them into starting a Sunday project and coming out to the vineyard. They would borrow some surveying instruments from the department. So we then began to put lines up for vineyard blocks and make corner markers of pipe that would be set in concrete so there would be more or less permanent markers for the blocks that we could locate."

"So I think this was the first time we actually outlined vineyard blocks, and we began using a logical system of calling the whole block 'A' or 'B' after a capitalized letter. Then, within the block we numbered the rows in a certain directional way. Then the vines within the rows. So it was a complete pattern, and it was systematized for the first time."

"This proved to be very desirable because I think ever since then our vineyard foreman and others have used a similar pattern, and we always know that vine numbers, for example are counted from west to east....and the row numbers always number from north to south because we started the early block that way. That was carried over in the relocation of new vineyards and has carried on to our new plantings". 56 Harold P. Olmo, Plant Genetics and New Grape Varieties, California Wine Oral History Project, Regional Oral History Office, University of California, Berkeley, interview conducted by Ruth Teiser, pages 87-88 (Regents of the University of California, 1976).

That numbering system or a variation thereof was used for the foundation vineyards from 1955 to 2018. The Hopkins Foundation Vineyard contained blocks A through L and was four blocks wide (A-D) and three blocks deep (A-D, E-H, I-L). Blocks A-D were set back parallel to Hopkins Road and were planted with rootstocks. The remaining blocks contained grape scion varieties.

The new Hopkins Foundation Vineyard was planted with both Registered and Non-registered clones/selections. The intermixture was allowed in part because plant pathologists at the time did not believe that most viruses could spread from plant to plant. Former FPS Production Supervisor Mike Cunningham recalls that "Goheen swore that viruses did not move plant to plant" and that the old foundation vineyard was a conglomeration of known virused plants and virus-tested plants. FPMS would sell a popular selection like Cabernet Sauvignon 08, which might be planted next to a vine that showed symptoms of leafroll virus. 57 Interview with Mike Cunningham, former FPMS/FPS Production Supervisor, February 24, 2015. Meticulous care is taken today to ensure that only vines that have been thoroughly tested and qualified for the Grapevine R&C Program are allowed in foundation plantings. While that high standard is accepted as a matter of course in 2018, such was not always the case.

As time went on, vines that were included on the List of Registered Vines for the Grapevine R&C Program were qualified in vineyards other than the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. The Division/Department of Viticulture maintained vineyards at Davis beginning in 1908 when it was known as the University Farm. Those vineyards were maintained by faculty for such things as research, variety collection, breeding and clonal trials - often without regard to disease status of the vines. The Department of Viticulture distributed materials upon request to growers all over the world since the 1920's. 58 Minutes of Meeting of the California Grape Certification Association, at Lodi CA, December 19, 1952; in Olmo collection D-280, box 31: 8, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The Department of Viticulture blocks were located at Armstrong Vineyard adjacent to Block A, the first foundation vineyard. Later on, they were located on Hopkins Road south of the FPMS foundation vineyard.

The status of the vineyards of the Department of Viticulture was at times ambiguous. In the 1970's and 1980's, the Department of Viticulture had "indexed" grapevine material in their vineyards that were situated south of the FPMS Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. When a customer called FPMS and requested a variety that was not then part of the FPMS Hopkins Foundation Vineyard collection, Goheen would index a vine of that variety that was planted in the Department of Viticulture vineyard. If the test was negative, that vine would become one of the vines in the Grapevine R&C Program. The procedure was used by Goheen because he did not believe at the time that virus diseases spread from vine to vine in the vineyard.

CDFA included the Department of Viticulture vineyards east of the reservoir in the annual inspections of "Registered vines" as recently as the 1980's when CDFA came to inspect the FPMS Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. Mike Cunningham remembers that Goheen, Cunningham and 4 or 5 CDFA staff would walk the vineyards for two days every spring and fall. Goheen would begin the first morning and talk for three hours in the first row, would say "oh, it's almost lunch time" and say they should walk a few more blocks. FPMS staff collected and distributed grapevine cuttings for orders from the "M-O", R, S and T blocks and Tyree vineyard of those Viticulture vineyards until the leafroll crisis in 1992-93 (discussed in Part 2 of the FPS story). Cunningham and FPS Grape Program Manager Susan Nelson-Kluk recall that FPMS planted two of its own mother blocks near the reservoir in the Viticulture area on Hopkins Road.

FPMS staff had a synergistic and close working relationship with staff from the Department of Viticulture. One of the side effects of that working relationship in the early days of FPMS was that FPMS distributed to customers both their own indexed ("certified") grapevine material as well as "non-certified" material to satisfy requests made to the Department of Viticulture. 59 Minutes of the Committee Meeting of Foundation Plant Materials Service, November 22, 1961, FPS collection AR-050, box 1: 19; Memo to Dean Briggs from Nyland, Brooks, and Amerine, dated April 22, 1958, FPS collection AR-050, box 33: 2 and box 26: 17, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. Goheen expressed concern about that practice to Maynard Amerine (Chair, Department of Viticulture) by letter in March of 1959, reasoning that the use of the word "Foundation" in the FPMS name implied that all material distributed by the service was tested and found to be free of serious virus trouble. Goheen felt that the misrepresentation might endanger the program. 60 Letter A.C. Goheen to Maynard Amerine, dated March 9, 1959, on file FPS collection AR-050, box 33: 2, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. FPMS continued to distribute non-registered ("not certified") grapevine material until as late as 1990. 61 Memo to Susan Nelson-Kluk and Burt Ray from Cornelius Ough and Mark Kliewer, dated October 21, 1981, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 10 (Tyree and Armstrong vineyards), Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

FPMS moved to a new foundation vineyard again beginning in 1983, in part to isolate Registered (R) vines from Non-registered (N) vines. At a meeting of the FPMS Technical Advisory Committee on April 17, 1990, FPMS decided to phase out the vines in the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard over a 5-year period because that vineyard did not meet isolation requirements in the Grapevine R&C Program regulations. The vines would continue to be tested for fanleaf virus every other year until all the selections could be repropagated to the new Brooks vineyard. Collection of foundation wood from the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard and Tyree block belonging to Viticulture would be allowed on a vine by vine basis in the interim. CDFA later agreed to that plan. 62 Minutes, FPMS Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, April 17, 1990, on file AR-050, box 23: 12; Minutes FPMS Industry Advisory Committee Meeting, April 23, 1990, AR-050, box 23: 13; Minutes FPMS Grape Committee Meeting, November 5, 1991, attached to 1992 FPMS Annual Report, AR-050, box 29: 49, all on file Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

At that Technical Committee meeting, the suggestion was made that FPMS also consider phasing out distribution of all Non-Registered vine material. Production Superintendent Mike Cunningham estimated that about 1% of grape material distributed by FPMS at that time was Non-Registered and indicated that customers agreed to purchase Non-Registered stock on an "as is basis". Today, only grapevine material that has qualified by regulations is allowed to be planted in the FPS foundation vineyards. FPS no longer distributes Non-Registered grapevine materials.

The old foundation vineyard west of Hopkins Road, most of which was planted in the 1960's, was abandoned as a source of foundation stock by 1993. Many of the vines were more than 25 years old at that time and were starting to show decline from eutypa. The vineyard was completely removed in spring of 1999. Most of the commercially important selections had been retested, qualified and planted in the new Brooks Foundation Vineyard. The material not qualified for transfer to the Brooks Foundation Vineyard was transferred to the UCD Viticulture & Enology Department or the USDA National Clonal Germplasm Repository (NCGR) at Davis. 63 FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, October 1998, page 2; FPMS Newsletter, October 1983, pp. 3-4.

Classic Foundation Vineyard (Brooks Farm) (1983)

A new foundation vineyard was planted beginning in 1983 on University land assigned to FPMS in the Brooks Farm area one mile east of the old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. The initial foundation blocks were known as Brooks South and Brooks North. Brooks South block was established in 1983 with rootstock and scion selections propagated directly from the Hopkins Foundation Vineyard. Brooks North block was established in 1992 with scion selections only. 64 Memo to FPMS Technical Advisory Committee from Susan Nelson-Kluk, dated August 17, 1987, filed FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 11, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis; FPMS 1984 Newsletter, no. 4, October 1984, p. 4. Mike Cunningham stated that relocation of the vineyard permitted a better organization of the blocks used to produce rootstock by wider spacing between the varieties. 65 Minutes from FPMS Annual Meeting 1982, attached to FPMS Annual Report 1983, FPS collection AR-050, box 29: 50, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. After the crisis involving the rootstock AXR1, FPS developed St. George rootstock on which to graft the scions in the new vineyard. 66 Minutes FPMS Grape Technical Advisory Committee Meeting, November 26, 1990, AR-050, box 23: 13; Minutes, FPMS Grape Technical Advisory Committee, dated January 22, 1991, AR-050, box 23: 13, both filed in FPS collection AR-50, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The vineyard was cordon trained and trellised with funds provided by Grapevine R&C Program participants. 67 Minutes, FPMS Grape Industry Advisory Committee Meeting, November 5, 1991, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 13, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The vineyard became known as the "Classic Foundation Vineyard" once the new foundation at Russell Ranch was developed in 2010.

Goheen guided the FPMS grape program in the early 1980's and did not believe that clonal variation was an important quality factor within varieties. 68 Alley and Golino, ASEV 2000, supra, at p. 227. For that reason, when the selections were initially propagated for the new Brooks South Foundation Vineyard in 1983, Goheen instructed the FPMS staff to plant only one clone of each variety. He chose the clone (selection) with the most heat treatment days, and therefore, the highest likelihood of being free of virus. Cunningham remembers that staff was careful to select only healthy-looking clonal material.

Goheen's criterion meant that popular selections did not necessarily make the cut; for example, the first Chardonnay in Brooks South was not Chardonnay 04 (the most popular Chardonnay at FPMS) but rather Chardonnay 07. Two or three years later, nurserymen such as Rich Kunde, Glen Stoller, Luther Khachigian and Ray Tonella told FPMS that they wanted more selections in the new foundation vineyard because other clones were doing better than the single clones that had been selected for the Brooks Vineyard. The remaining FPMS clones with commercial potential were thereafter moved into the Brooks collection. 69 Interview with Mike Cunningham, former FPMS/FPS Production Supervisor, February 24, 2015.

The grape and wine industry developed an interest in clones in the 1980's. Around 1992, the nurseries saw that growers and winemakers favored certain FPMS clones such as Chardonnay 04, Cabernet Sauvignon 07/08/11, Merlot 15 and the Dijon Chardonnay clones. Rich Kunde asked FPMS to plant more Registered vines of the popular clones that the industry wanted and provided a list to Susan Nelson-Kluk. This caused FPMS to develop the Nyland block in the Brooks Farm Foundation Vineyard to avoid having to sell Non-registered material of the popular selections when there were insufficient Registered vines.

Cunningham relates that they treated Nyland like an "increase block", in the sense of planting many more vines than usual of particular selections at the request of industry. Up to 20 vines of 58 established popular selections were planted in 1995. By the time those vines were mature and ready for harvest, however, newly imported clones had become popular. FPMS had moved away from the established FPMS clones to French, Italian and other foreign grape varieties. The Nyland increase block did not work out as originally envisioned, although it was useful to researchers.

The final selections that were moved from the old Hopkins Foundation Vineyard to the Brooks Foundation Vineyard were planted at the Brooks Farm site in spring of 1992. The future goal was to collect Registered material for customers exclusively from the new Brooks vineyard by the 1994-95 season. 70 FPMS Newsletter, no. 12, November 1992.

Another special block in the Brooks (Classic) Foundation Vineyard was developed in response to a particular pathogen. Grape growers from the regions such as the Pacific Northwest (Oregon and Washington), New York and Canada constantly battle Agrobacterium vitis (A. vitis), a bacterium that causes crown gall disease. The disease is endemic in areas where cold weather or mechanical injury causes cracking on the roots, trunk and limbs allowing the bacterium to enter the vine. The presumptive treatment for A. vitis is shoot tip culture therapy.

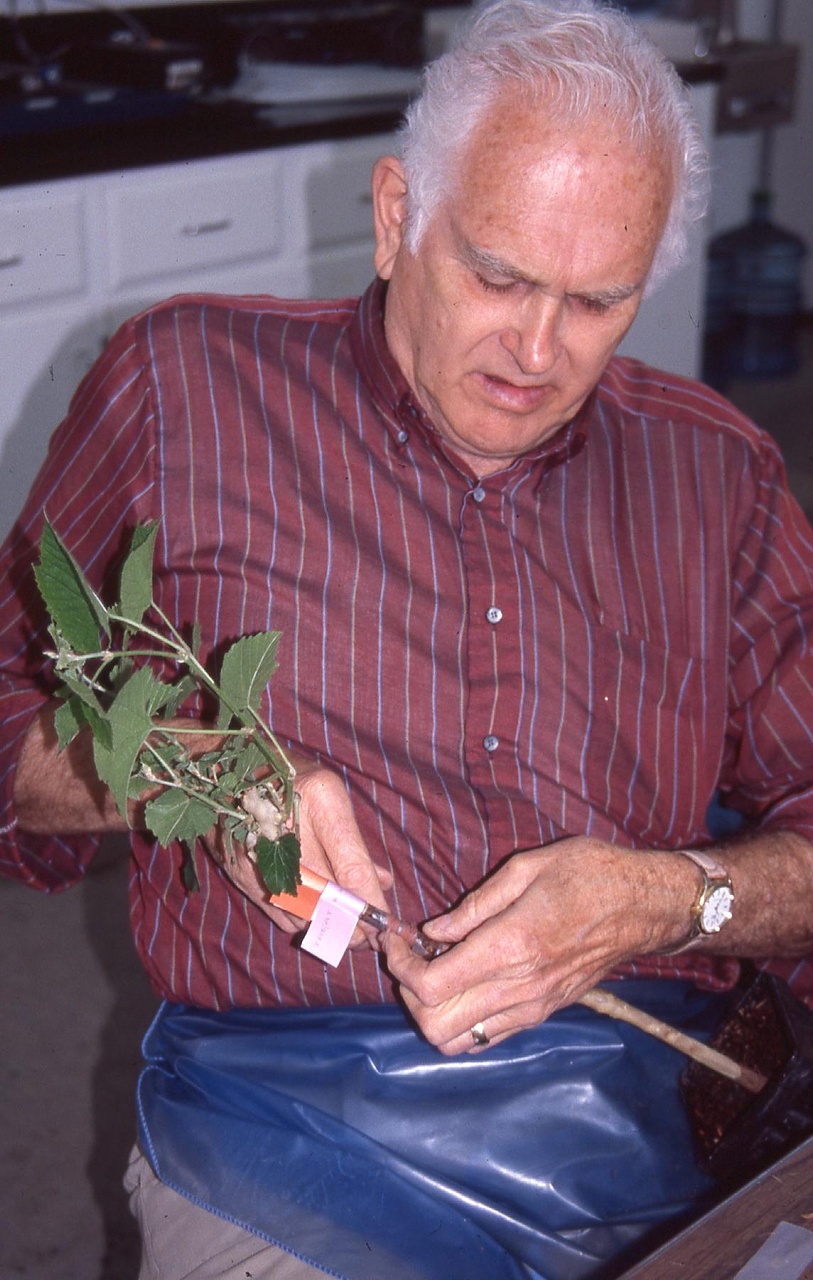

There are two types of shoot tip culture used to generate new plantlets: (1) microshoot (the tip cut is 0.5 mm or less), used to eliminate many pathogens including viruses; and (2) macroshoot (the tip cut is greater than 0.5 mm), which is known to eliminate A. vitis. Microshoot tip therapy is more difficult and requires much longer than macroshoot tip culture. Beginning in the early 2000's, FPS generated vines from 19 major rootstock varieties and 23 scion varieties using macroshoot tip culture therapy for what FPS called the "Next Generation" Foundation Vineyard. 71 Susan T. Sim and Deborah Golino, “Micro- vs. Macroshoot Tip Tissue Culture Therapy for Disease Elimination in Grapevines”, FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2010, pp. 12-15. Permission to use land near the Nyland and Brooks North blocks was obtained in 2002, and the new area was named the Goheen block. 72 Minutes, FPMS Grape Advisory Committee Meeting, November 13, 2002, FPS collection AR-050, box 23: 15, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. The nineteen rootstock selections were planted in 2005, and 23 wine and table grape selections were planted in 2008. 73 FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2008, p. 5.

FPS partnered with crown gall researcher Thomas Burr at Cornell University to develop a reliable screening test for crown gall using the new selections. The rootstock varieties all tested negative for crown gall in 2007. 74 FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2008, page 5. For a time, FPS marketed and sold the selections in the Goheen block as "Next Generation" material.

The Next Generation Vineyard was put on hold after the National Clean Plant Network (NCPN) was formed in 2007 and was eventually subsumed by the Russell Ranch Vineyard project. The vines created for the Next Generation vineyard using macroshoot tip tissue culture therapy were not eligible for the Russell Ranch vineyard, which requires vines produced by microshoot tip therapy. The words "Next Generation" are now more closely associated with high-throughput sequence testing for grapevine disease detection.

Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard (2010)

FPS has been the lead clean plant center for grapes since the National Clean Plant Network (NCPN) was formed in 2007. The NCPN is a voluntary association of grapevine plant centers that seeks to spread the message of the benefit of healthy grapevine materials and to develop state-of-the-art protocols for testing and treatment. The NCPN for Grapes made an important decision in February, 2009, to set a rigorous new standard for grapevine foundation material in the United States.

The NCPN standard is much more rigorous than the testing and treatment required to qualify for the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program. In 2010, the NCPN for Grapes approved a protocol (known as "2010 Protocol") specifying the requirements for qualification under the NCPN standard for foundation grapevines. The 2010 Protocol requires that all vines be created by way of microshoot tip tissue culture therapy (smaller tips) and test negative for a lengthy list of pathogens known to infect grapevine materials.

In response to the decision of the NCPN for Grapes, FPS created a foundation vineyard to house grapevines that meet the qualifications set forth in the 2010 Protocol. In 1990, UC Davis acquired a 1600-acre parcel of farmland known as Russell Ranch, located 4 miles west of the UCD campus. The property surrounds the Hamm House, which was built in the late 1860's and inhabited until 2002 by the Russell family, who were early developers of the City of Davis.

The approximate 1000 acres of the Russell Ranch farmland contiguous to the Hamm House property has been leased as prime farmland since 2003. FPS petitioned the University and obtained permission to use 100 acres of the Russell Ranch parcel primarily for a new foundation vineyard. The site is remote from other vineyards to reduce the risk of pathogen vector incursion.

The vineyard infrastructure was installed beginning in 2009. Planting began at Russell Ranch in 2011 with the rootstock varieties and some of the scions. All grapevines used to populate the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard were generated using microshoot tip tissue culture therapy. In 2010, selections from the Classic Foundation Vineyard that had already undergone microshoot tip tissue culture treatment began the rigorous testing required by the 2010 Protocol. Commercially desirable scion selections that had not undergone treatment were immediately prioritized and earmarked for microshoot tip culture therapy.

Once qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard, selections from the Classic Foundation Vineyard were assigned a new selection number that both preserved the prior identity of the selection and indicated that the selection had successfully completed testing to qualify under the 2010 Protocol. For example, Chardonnay 04 from the Classic Foundation Vineyard was renamed Chardonnay 04.1 in the Russell Ranch Vineyard. The goal was to move almost all of the selections from the Classic Foundation Vineyard to the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard.

The Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard (RRV) has been seriously impacted by the Red Blotch epidemic in California. As discussed in some detail in the following chapter (FPS into the 21st Century), Grapevine Red Blotch Disease is caused by the Grapevine red blotch virus (GRBV) and spread by various leafhopper vectors. FPS began a testing regimen for GRBV for the grapevines in its foundation vineyards in 2013.

Red Blotch virus was first detected in the Russell Ranch foundation vineyard in 2017. Five of the 4,132 vines (0.1%) in RRV tested positive in 2017. Those vines were immediately removed and destroyed. Since then, despite significant efforts to prevent the occurrence of the disease, the infection rate in the Russell Ranch vineyard has increased to 0.5% (24 or 4,406) in 2018, 7.1% (339 of 4,761) in 2019, and 18% (788 of 4,367) in 2020.

In contrast, Red Blotch infection rates have remained extremely low in the Classic Foundation Vineyard, ranging from 0% to 0.21% since 2013. None of the 4,270 vines in the Classic vineyard were infected in 2020.

In October of 2020, FPS advised its customers that the best course of action was to discontinue distributing material from the Russell Ranch vineyard. Grapevine material from the Classic Foundation vineyard (which represents the majority of clonal families from RRV) continues to be available for distribution to customers as of 2021. FPS tests all grapevine material for GRBV as dormant canes prior to shipping.

FPS and UC Davis planners are currently working on plans for a large greenhouse that will protect approximately 4,000 of FPS' most valued foundation grapevines. The greenhouse solution is viewed as essential to protect the material from vectors and continue to guarantee immediate access to clean plant material in case of field infection. In the interim, FPS is currently renting two greenhouses from the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences to temporarily house valuable clonal selections as mother vines in a protected environment.

GRAPEVINE TESTING AT FPS

Testing of grapevines for virus and virus-like conditions is complicated. Some of the biological testing methods have been used for decades and have endured the test of time in terms of producing reliable results. Molecular testing methods have improved over time and are sensitive and specific in targeting particular diseases. FPMS/FPS has employed a combination of testing protocols on the grapevine collection to detect problems at the earliest stage possible and maintain a "clean" foundation collection.

The federal government USDA/APHIS protects against the entry of grape viruses into the country and dictates the requisite testing that allows an imported grapevine to be released from quarantine into the U.S. Post entry quarantine testing is conducted at dedicated grape importation and quarantine facilities such as FPS. Once a grapevine is in the United States and is not in quarantine, there are no national restrictions on the movement of plant material between the states. Each state addresses the issue for itself. A few states such as Washington and Oregon have enacted state quarantine regulations for grapes entering from other states.

Clean plant programs are administered at the state level and are monitored by a state regulatory agency such as a Department of Agriculture. The goal of a state certification program is to produce healthy, disease-tested plant material to commercial growers of that crop. A state that wishes to create a program offering certified grape material establishes the rules by law and/or regulations and sets up a system for creation of the certified vines. The key components of a clean plant program are testing and/or treatment of grapevine material, an isolated foundation vineyard that serves as a source of the grape selections, a nursery industry to multiply the grapevine material and distribute them to growers, an oversight agency to monitor compliance and, for California, a trueness to type evaluation of program vines. The diseases for which testing is required, usually viruses and some bacteria, may include many of the same testing and disease elimination procedures as the federal importation program.

California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program

The clean plant program in California is known as the California Grapevine Registration & Certification (R &C) Program and is regulated by the Department of Food & Agriculture (known as the Department of Agriculture until 1972). Program regulations applicable to FPMS/FPS have from the outset specified that all grapevine material destined for eventual sale as certified vines be "free of certain diseases", mostly viruses. The specific diseases for which testing is required by the regulations have changed over the decades since the program began in 1958. A review of the significant provisions for testing will provide context for the later discussion about key events in FPMS/FPS history. 75 D.A.Golino, M. Fuchs, M. Al Rwahnih, K. Farrar, A. Schmidt and G.P. Martelli, ''Regulatory Aspects of Grape Viruses and Virus Diseases: Certification, Quarantine, and Harmonization'', Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management, p.p. 581-587, edited by Baozhong Meng, Giovanni P. Martelli, Deborah A. Golino and Marc Fuchs (Springer International Publishing AG 2017).

First, some preliminary words about nomenclature. Many papers and articles in support of the clean plant program in the early years used the words "virus free" in reference to the grape material tested and released at UC Davis. In the 1970's, the words "virus free" appeared in conjunction with advertisements for nursery stock produced under the California Grapevine R & C Program.

The use of "virus free" in advertisements was eventually prohibited in California because it was considered misleading. 76 Memo from CDFA to Grapevine R&C Program Participants, dated October 17, 1972, filed in FPS collection AR-040, box 25: 37, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis. No disease elimination treatment or virus test is considered to be infallible. New viruses are periodically identified, and virus can spread into non-isolated virus-tested vines by way of vectors. FPS uses the words "virus tested" to describe its foundation grapevines, which continue to be inspected and tested regularly after installation in the foundation vineyard.

CDFA adopted the original regulations for the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program in two phases. Phase one defined the rules for "Registered vines" on September 8, 1956 (Regulations for Registration of Grapevines Inspected and Tested for Virus Diseases). A "Registered vine" was defined as one that has tested negative for specific diseases and is eligible for planting in the foundation vineyard at UC Davis or in grower mother blocks. 77 Title 3, California Administrative Code sections 3024 et. seq. (effective September 8, 1956). The regulations required that the foundation vineyard be isolated from non-registered grapevines, regularly retested and regularly inspected by CDFA.