Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis -

October, 2018

© 2018 Regents of the University of California

Zinfandel: Croatia to California

-- H.P. Olmo and M.A. Amerine, Wines & Vines, August 1938.

The grape known in the 19th century as "the Zinfandel" is the only important Vitis vinifera wine variety identified closely with the state of California. Zinfandel's enigmatic journey to California has never been completely resolved and possibly never will be. The best evidence suggests that the variety came to California around 1850. There was no vine named "Zinfandel" in Europe at the time. The origin of the name "Zinfandel" is as mysterious as is the origin of the variety. 1 H.P. Olmo and M.A. Amerine, ''Zinfandel'', Wines & Vines 19(9): 3-4 (August, 1938). Theories and facts surrounding the origin and identification of California's Zinfandel have been reported thoroughly in scientific journals and books, including historian Charles L. Sullivan's Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine (2003). 2 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London (2003).

In addition to the Zinfandel vineyards in California, clonal lines for the variety have evolved independently over time in two other countries. Definitive genetic analysis in 2003 ultimately made a crucial link when it found that California's Zinfandel, Italy's Primitivo and Croatia’s Crljenak kaštelanski/Pribidrag (now known as Tribidrag) all share the same DNA profile.

3 E. Maletić , I. Pejić, J. Karoglan Kontić, J. Piljac, G.S. Dangl, A. Vokurka, T. Lacombe, N. Mirošević, and C.P. Meredith, “Zinfandel, Dobricic, and Plavac mali: The genetic relationship among three cultivars of the Dalmatian Coast of Croatia”, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 55: 174-180 (2004);

E. Maletić, I. Pejić, J. Karoglan Kontić, J. Piljac, G.S. Dangl, A. Vokurka, T. Lacombe, N. Mirošević, and C.P. Meredith, “The Identification of Zinfandel on the Dalmatian Coast of Croatia”, In: VIII International Conference on Grape Genetics and Breeding, E. Hajdu & E. Borbás (Eds.), Acta Hort 603, ISHS (2003), pp. 251-254.

Vines from all three sources are included in the foundation grape collection at FPS.

Although the origin of the Zinfandel in California remains uncertain, the most plausible source seems to be the Austrian Imperial Nursery collection in Vienna, from where an amateur horticulturist named George Gibbs brought the grape to Long Island, New York, in the 1820's. At that time, the Austrian Empire included the kingdom of Hungary, of which the territory now known as Croatia was a part. This source takes on particular significance given the discovery of ancient Zinfandel vines in Croatia in 2001.

In the early 1800's in the United States, Zinfandel (known then by names such as Zinfindal and Zenfendel) was used as a table grape grown in hothouses on the East Coast. An 1830 text by William Robert Prince (A Treatise on the Vine) mentions a “Black Zinfardel of Hungary” in a list of foreign varieties of recent introduction to the United States. 4 Charles L. Sullivan, 2003, supra at pp. 13-19. Zinfandel’s arrival in California probably occurred around the time of the Gold Rush. A search of public records by Sullivan revealed that many shipments of Vitis vinifera varieties, including Zinfandel (“Zeinfandall”, “Zinfardel”), were sent from the East Coast to the West Coast in the 1850’s by men such as Capt. Frederick Macondray and Anthony P. Smith. Sullivan reports that Antoine Delmas imported what he believed was Zinfandel to Santa Clara in 1852 under the name "Black St. Peters". 5 Charles L. Sullivan, 2003, supra at pp. 26-27, 65.

Col. Agostín Haraszthy has in the past been credited as the first to bring the Zinfandel grape to California when he travelled to Europe in 1861 to research wine cultivars. Historians Thomas Pinney and Charles Sullivan have persuasively cast doubt on that conclusion. 6 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America, vol. I, pp. 271-284, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London (1989); Charles L. Sullivan, 2003, supra, pp. 51-71. Zinfandel was not named on the list of varieties Haraszthy brought back with him from Europe. Haraszthy contemporary Charles Wetmore, Chief Executive Viticultural Officer of the State Board of Viticultural Commissioners, specifically noted in a version of his 1884 “Ampelography” that Zinfandel was in California long before Haraszthy travelled to Europe in 1861. 7 Charles Wetmore, Ameplography of California (n.d., n.p.; “Reproduced and revised from San Francisco Merchant of January 4 and 11, 1884”), p.10.

Zinfandel began to be recognized in California as a wine in its own right in the 1860’s, and the largest plantings were in Napa and Sonoma counties. The new wine industry realized that the cultivar was not a French wine grape and did not satisfy the demand for that type. However, Zinfandel’s success alerted the infant wine industry in California to the better qualities possessed by other quality wine grape imports from Europe. 8 Olmo and Amerine, Wines & Vines 19(9), supra.

U.C. Professor E.W. Hilgard recognized the suitability of the variety to the state in his 1879 Report to the President of the University of California:

“A correct appreciation of this necessity has led to the introduction on a large scale of the tart, acid and highly colored Austro-Hungarian “Zinfandel” grape – the opposite extreme as compared with the Mission. Even under the fervid sun of California, the pure product of this grape remains too harsh for most palates; but its mixture with the Mission….produces an admirably blended product. Of course the combination of the acid and body-yielding Zinfandel with grapes of higher quality than the Mission may be made to produce still finer results.” 9 Report of E.W. Hilgard to the President of the University, Supplement to the Biennial Report of the Board of Regents for 1878-1879, p. 63, College of Agriculture, University of California, Sacramento, Supt. State Printing (1879).

Hilgard studied Zinfandel wines in the 1880’s as part of the university’s newly established program for evaluating wine quality. Zinfandel grapes from Charles Krug in St. Helena were the second sample to be submitted to the University of California in 1880 for analysis of grapes and musts. 10 E.W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in Charge to the Board of Regents, being a part of the Report of the Regents of the University for 1880, p. 89, College of Agriculture, University of California, Sacramento (1881). Hilgard’s report the following year on the wines made from the previous year’s grapes noted that only a few of the wines made in the laboratory from single grape varieties yielded satisfactory results, the best being Chasselas, Mátaro and Zinfandel. Hilgard advised judicious blending with Zinfandel to produce the best results for what was then known as Bordeaux or "claret" wines. 11 E.W. Hilgard, ‘Vintage Work in the Viticultural Laboratory, 1884’, Agric. Expt. Sta. Bulletin #23, Berkeley (November 20, 1884); E.W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in charge to the President, being a part of the Report of the Board of Regents for 1881-1882 (also called Biennial Report), p. 125, College of Agriculture, University of California, Sacramento, CA (1882). Zinfandel was blended early on with Black Malvoisie (Cinsaut) and the Mission grape, but finer blending varieties (e.g., Mátaro, Cabernet Sauvignon) were later recommended. 12 Report of E.W. Hilgard to the President of the University, 1879, supra at p. 63; Charles Wetmore, Ampelography revised, San Francisco Merchant, supra at pp. 10-11.

Zinfandel emerged as an exceptional grape variety for wine making in northern California in the 1880’s. Hilgard estimated that Zinfandel accounted for half the plantings in California in 1884. Hilgard’s colleague Frederic Bioletti commented in a report that “the variety is too well known in California to require any remarks on its general character”. Zinfandel actually accounted for approximately 2/5 of the state’s vineyard acreage in 1884. In 1887, Zinfandel grapes sold for $14-16 per ton, which was more than Black Malvoisie (Cinsaut) and Mission. For perspective, high quality grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot noir sold for $25-30 per ton that same year. 13 Olmo and Amerine, Wines & Vines 19(9), supra; E.W. Hilgard, Bulletin #23, supra.

Charles Wetmore characterized Zinfandel as the only notable exception to the similarity of early California wines to those of Europe; he wrote that, “although Hungarian, [Zinfandel] is more known now in America than in Europe, and is the beginning of a new type of which we may be proud”. 14 Charles Wetmore, Commissioner at Large, First Annual Report Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, 1881, pp. 48-49. Foreshadowing the White Zinfandel craze of the mid-20th century, Wetmore noted in his 1884 Ampelography that Zinfandel should be classed as a white wine grape of importance for the warmer Yolo and San Joaquin Counties. 15 Charles Wetmore, Ampelography revised, San Francisco Merchant, supra at p. 8.

In 1929, Viticulture Department Chair Bioletti described Zinfandel as the best known and most largely planted of the California wine grapes and recommended it for the north coast region. 16 Frederic T. Bioletti, Elements of Grape Growing in California, California Agricultural Extension Service, Circular 30, March 1929 (revised April 1934), College of Agriculture, University of California, p. 31. In their feature article on “Zinfandel” for the Wines & Vines series, Harold Olmo and Maynard Amerine wrote that the variety does best in cooler coastal regions where there is sufficient warmth to ripen the grapes before the heavy rains begin. 17 Olmo and Amerine, Wines & Vines 19(9), supra. Amerine and A.J. Winkler observed in 1944 that “[t]he Zinfandel has a permanent place in California for a distinctive type of wine”. 18 M.A. Amerine and A.J. Winkler, ‘Composition and Quality of Musts and Wines of California Grapes’, Hilgardia, vol. 15(6): 562 (February, 1944). They opted not to recommend increased plantings of Zinfandel to growers at that time, reasoning that an incremental increase in plantings would not result in good profits given the extensive existing acreage. Amerine and Winkler did recommend Zinfandel to California growers in 1963 for well-drained dry locations. The university included Zinfandel among the varieties in their clonal research trials in the 1970’s. 19 Amerine and Winkler, Hilgardia, at pp. 47-48; C.J. Alley, “An update on clone research in California”, Wines & Vines 58(4): 31-32 (April 1977).

The affinity of the state for the variety has remained constant. In a California grape acreage survey in 1936, Zinfandel acreage was estimated at 53,343 (chiefly San Joaquin, Sonoma and San Bernardino Counties). 20 Olmo and Amerine, Wines & Vines 19(9), supra. Eighty years later in 2017, Zinfandel was the 4th leading wine grape variety in California in total acreage behind Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot noir. The California Department of Food and Agriculture reported 43,210 total acres of Zinfandel and 1,335 acres of Primitivo grapes planted in 2017. 21 California Grape Acreage Report, 2017 Summary, California Department of Food & Agriculture, cooperating with the USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service, published April 19, 2018. Although Zinfandel has a presence in most of the state where grapes are grown, the most significant plantings are in San Joaquin County (17,867 acres), Sonoma County (4,996 acres), Fresno and Madera, Amador, Mendocino and San Luis Obispo Counties. Those California counties lie in all five regions on the Winkler heat summation scale, from the coastal valley and hill areas (regions I-III) to the Central Valley counties and portions of the Sierra foothills (regions IV-V).

Zinfandel wine takes many forms, in part due to the quality of grape, the vineyard management practices applied and the location of the vineyard within California’s varied topography. The wine produces a recognizable flavor, which has been identified as fruity, raspberry like, and aromatic. 22 Charles L. Sullivan, 2003, supra; Olmo and Amerine, Wines & Vines 19(9), supra. Zinfandel grapes grown in the hotter areas of the Central Valley (regions IV-V) are frequently made into white or pink Zinfandel, a popular wine with a higher sugar and lower alcohol content. Late-harvested Zinfandel with its high alcohol content is appropriate for dessert wines in the style of port. In more recent years, Zinfandel wine produced from “old vines” grown on hillsides in California coastal valleys or the Sierra foothill region has been promoted as having more concentrated flavors.

Italy

While Zinfandel matured into California’s state wine, producers of wine from a grape variety named Primitivo developed its unique reputation in Italy. The Primitivo grape is grown principally in Puglia (Apulia), a long fertile region along the Adriatic Coast in southeast Italy. Puglia, like California, experiences mild wet winters and hot summers with scarce rainfall. The name “Puglia” derives from the Roman a-pluvia or "lack of rain". 23 Jancis Robinson, The Oxford Companion to Wine (Oxford University Press, 3d ed., Oxford, England, 2006), p. 553. Primitivo wines are often used in Italy to fortify red wines made in cooler regions because of the high alcohol and intense pigmentation of the Primitivo wines.

One theory posits that the Primitivo grape was taken across the Adriatic Sea from Croatia to Puglia in the 18th century. Before the variety was known in Puglia as Primitivo, it was apparently known as Zagarese, allegedly named after the city of Zagreb in Croatia. 24 Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, José Vouillamoz, “Tribidrag”, WINE GRAPES (HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY, 2012), p. 1085; E. Maletić et al., 2004, supra. Dr. Giovanni Martelli of the Istituto di Patalogia Vegetale in Bari, Italy, states that the first recorded presence of the Primitivo grape in Italy was in Gioia del Colle, a small town of Puglia located in the hills of Murgia. Gioia is situated ½ way between the Adriatic and Ionian Seas (east/west) and ½ way between Bari and Taranto (north/south). Mr. Francesco Filippo Indellicati, a local priest who was also a learned amateur botanist and agronomist, made a note of the Primitivo grape in Gioia town records in 1799.

Today, over 70% of the vineyards in Puglia are in the plains with very high daytime temperatures. Primitivo is primarily cultivated on the western side of the flat Salento peninsula in Puglia near the city of Manduria, which is about 100 km southeast of Bari. Puglia and the Croatian region on the Dalmatian Coast have similar climatic conditions - marine influence, humidity, cool summer nights. The Salento peninsula (Puglia), central and southern Dalmatia, and certain warmer areas in the Central Valley of California are in Winkler climate zone IV. However, the growing season is drier in California than that of the central Dalmatian Coast. 25 E. Maletić et al., 2003, supra.

USDA-ARS Plant Pathologist Dr. Austin Goheen was first exposed to the Italian grape in the late 1960’s. He was dining one evening in 1967 with Martelli in Italy when he tasted a wine he thought was a Zinfandel. The two men then went to a vineyard located between Bari and Gioia del Colle (40 km southeast of Bari), where Goheen collected the plant material that eventually became Primitivo 03 at Foundation Plant Services (FPS). He brought some plant material back to the USDA facility in Davis, California. Primitivo and Zinfandel were planted side-by-side in California and appeared to be the same variety. 26 E. Maletić et al., 2003, supra; Nikola Mirošević and Carole P. Meredith, “A review of research and literature related to the origin and identity of the cultivars Plavac mali, Zinfandel and Primitivo (V. vinifera L.)”, Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus 65 (1): 45-49 (2000). Subsequent genetic analysis at UC Davis in 1994 confirmed that Zinfandel and Primitivo share the same DNA profile. 27 E. Maletić et al., 2003, supra; J.E. Bowers, “The use of simple sequence repeat (SSR) and amplification fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers for analysis of interrelationships and origins of winegrape cultivars”, Ph.D. thesis, 1998, University of California, Davis.

Although Zinfandel and Primitivo are the same variety, some clonal divergence seems to have resulted over time attributable to a lengthy period of independent development of the two clonal lines in California and Italy. UC Professor Carole Meredith explained in a letter to the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (now, Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau) that intravariety differences are common among old and geographically dispersed varieties. 28 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, Department of the Treasury, “Proposal to Recognize Synonyms for Petite Sirah and Zinfandel Grape Varieties (2001R-251P)”, RIN 1512-AC65, 27 CFR 17312, vol. 67, no. 69 (April 10, 2002). It is reportedly difficult to visually distinguish California Zinfandel selections from the Primitivo selections when they are growing together in the field, but there are some subtle differences in appearance. 29 Nikola Mirošević and Carole P. Meredith, 2000, supra. Primitivo’s berries are slighter smaller than Zinfandel’s; the size discrepancy is noted if the two grapes are simultaneously viewed side by side or if one measures the berries. 30 Personal communication by Dr. Andy Walker, Department of Viticulture & Enology, University of California, Davis, to author on May 10, 2007. Clonal comparison studies in California (described below) have shown looser clusters and less rot for Primitivo vines in the state. Meredith indicated in the letter to the Bureau that small differences between the clones such as berry size or fruit composition could be significant for winemaking.

The issue of whether Zinfandel and Primitivo may be used as synonyms on wine labels in the United States has been addressed periodically for several decades. The former Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (now, the TTB) regulates the use of grape variety names on wine labels. In 1985, the Bureau ruled that the two names could not be used interchangeably and must be listed as separate varieties because of ambiguity associated with the use of the name “Primitivo” on vines in Italy. After the scientists at UC Davis determined the genetic identity of the two grapes in 1994, the Bureau indicated its inclination to revisit the issue in 2002 in light of the DNA evidence showing similar DNA profiles. Meredith noted possible minor clonal differences between the two grapes but opined that the two were the same grape variety. The Bureau pointed to a 1999 European Union ruling that recognized “Zinfandel” as a synonym for the Primitivo grape and announced its intention to issue a ruling along similar lines. Comments on the proposed action were solicited. 31 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, Department of the Treasury, “Proposal to Recognize Synonyms for Petite Sirah and Zinfandel Grape Varieties (2001R-251P)”, RIN 1512-AC65, 27 CFR 17312, vol. 67, no. 69 (April 10, 2002).

Extensive feedback was received during the comment period. The gist of the objection to synonomy related to the possible adverse impact on the California wine industry should the Bureau approve foreign wine labels using the Zinfandel name. There was concern over the quality and integrity of Zinfandel wine in the United States if synonomy were approved. Some comments claimed that wine was made in Italy from grapes named “Primitivo” but which in fact were grapes other than Zinfandel. Others predicted confusion over the use of foreign labels for a wine so closely associated with California. Some commented that the clonal differences between Primitivo and Zinfandel result in distinctly different wines. Dr. Meredith followed the public comments with a letter stating that the study of the two clonal lines at Davis had been based on a limited sample of two Primitivo vines, while it was possible that the variety “Primitivo” in Italy could be heterogeneous and could include vines not identical to Zinfandel. 32 Letter to Chief, Wine and Beer Branch, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, from Dr. Carole P. Meredith, dated 25 November 1992, filed in Olmo collection (D-280), box 58, folder 34, Special Collections Department, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

The ruling on the issue was postponed indefinitely. The TTB continues to maintain Primitivo and Zinfandel as separate prime grape variety names used to designate American wines. Consequently, as of 2018, Zinfandel and Primitivo may not be used as synonyms on wine labels for wines made in the United States.

Croatia

The search for the “true origin” of the Zinfandel grape took a new path in the 1990’s. Many speculated that Zinfandel could have its origin in Hungary or other areas of Eastern Europe, practically all of which was within the Austrian Empire at the time Zinfandel was first brought to the United States. Researchers from the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Croatia, Drs. Edi Maletić and Ivan Pejić, collaborated with Dr. Carole Meredith at UC Davis to solve the mystery of the origin of Zinfandel.

In 1998, Maletić and Pejić and local experts in Dalmatia identified a possible candidate for the ancestor of Zinfandel in Croatia. An autochtonous Dalmatian grape called Plavac mali resembled Zinfandel. Maletić and Pejić consulted with Meredith, who assisted with the search for Plavac mali samples on the coast of Croatia. She took the samples to her laboratory at UC Davis for DNA testing against Zinfandel and Primitivo. 33 Nikola Mirošević and Carole P. Meredith, 2000, supra. The profiles did not match. The similarity of Plavac mali to Zinfandel was later explained by the discovery that Zinfandel is one of the parents of Plavac mali. 34 E. Maletić et al., 2004, supra.

Drs. Edi Maletić and Ivan Pejić examine a Plavac mail vine on the island of Solta on the Dalmatian Coast

The Croatian scientists continued to explore the vineyards on the hills descending to the sea in coastal Croatia and the nearby islands for the source of California’s Zinfandel. The Kaštela region is an ancient wine-growing area in Eastern Europe, from the time before the Roman occupation. The climate is characterized by long and warm summers and mild winters, although the climate in Kaštela is wetter than California is during the growing season. 35 E. Maletić et al., 2004, supra.

In 2001, Maletić and Pejić discovered another local vine named Crljenak kaštelanski (“the red from the town of Kašteli”) in a coastal town in the Kaštela region named Kaštel Novi in central Dalmatia north of Split. Crljenak kaštelanski was once prominent in Dalmatia and either originated in Kaštela or had a lengthy association with that region. The Crljenak kaštelanski vines in that region were nearly extinct in 2001. The scientists were able to collect samples from the nine vines that remained at that time.

In 2002, additional vines known locally as Pribidrag were found in the Dalmatian coastal town of Omiš, south of Split.

The Crljenak kaštelanski and Pribidrag vines looked morphologically identical to Zinfandel. Maletić and Pejić provided the samples from both locations to Meredith, who was able to confirm that the DNA profile of the two sets of rare vines was identical to Zinfandel. 36 E. Maletić et al., 2004, supra.

The results were presented at the Zinposium in Santa Rosa, California, on June 15, 2002 and at the International Conference on Grape Genetics and Breeding in Hungary in 2003. Both Croatian scientists Maletić and Pejić and Carole Meredith appeared at the Variety Focus: Zinfandel event on the U.C. Davis in May of 2007 and told the story of solving the mystery of the origin of Zinfandel. The entire series of presentations from that event may be viewed on the Foundation Plant Services website (http://fps.ucdavis.edu) in the Grapes section under “Variety Focus Presentations”.

Croatian scientists have attempted to define the possible age of the Zinfandel variety using records and herbarium specimens. They identified a 90-year-old herbarium specimen in Split, Croatia, among a collection of indigenous Croatian grapevine varieties. The specimen bore the name Tribidrag. Not only was the name almost identical to that of Pribidrag, a local synonym for Crljenak kaštelanski, but the Tribidrag and Pribidrag vines had similar morphology. A subsequent comparison using specialized techniques for analyzing ancient DNA showed that the Tribidrag herbarium specimen had an identical microsatellite profile to that of the American cultivar Zinfandel and the Italian Primitivo. 37 Nenad Malenica, Silvio Šimon, Višnja Besendorfer, Edi Maletić, Jasminka Karoglan Kontić and Ivan Pejić, “Whole genome amplification and microsatellite genotyping of herbarium DNA revealed the identity of an ancient grapevine cultivar”, Naturwissenschaften 98: 763-772 (2011).

80-90 year old Tribidrag herbarium specimen

The name “Tribidrag” is derived from a Greek phrase meaning “early ripening”. The etymology mirrors the Italian name for the cultivar, Primitivo, which is derived from the Latin primus meaning “first”. 38 Valentin Putanec, ‘Etymology 27-35’, Journal of the Institute of Croatian Lanuage and Linguistics, vol. 29:(1), December 2003; Jancis Robinson et al., WINE GRAPES, supra, at p. 1087. “Tribidrag” appears in historical documents in Croatia and Austria, which place cultivation of the Tribidrag grape in Croatia at the beginning of the fifteenth century. The scientists inferred from the totality of the evidence that Zinfandel was cultivated in Croatia as early as the 1400’s under the name Tribidrag. Tribidrag is the oldest known synonym for the variety and is now used as the preferred name in Europe and Croatia pursuant to the rule of anteriority (precedence for oldest name). 39 Nenad Malenica et al., 2011, supra; Robinson et al., WINE GRAPES, supra, at pp. 1085, 1087.

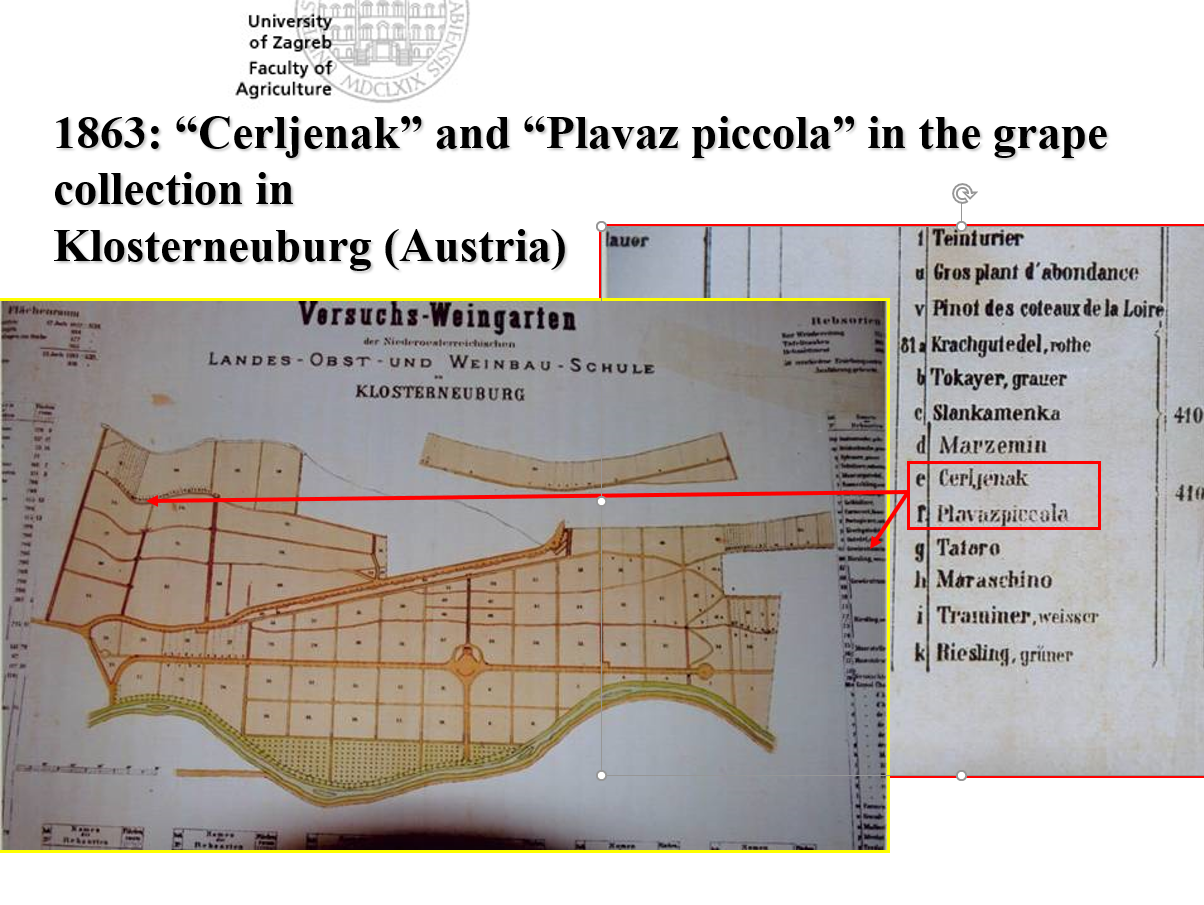

There is persuasive evidence for attributing a Croatian origin to the Zinfandel variety. A grape named “Cerljenak” was found on an 1863 map in the grape collection in Klosterneuburg (Austria). That fact is consistent with the theory that Zinfandel made its way to California in the 1800’s from the Austrian Empire or Kingdom of Hungary (which included Croatia) via nursery sources in New York State. At the Variety Focus at UC Davis in 2007, Ivan Pejić displayed a photograph of the 1863 map of the collection at Klosterneuburg and the variety list with the name “Cerljenak” as part of his presentation.

The Croatian cultivar now known by the primary name Tribidrag and another old Croatian variety from southern Dalmatia, Dobričić, are the parents of the most important red wine grape in Croatia, Plavac mali. Many of the alleles present in the parent grapes are more common in the Croatian gene pool than in the general population of V. vinifera varieties, such as those from nearby Greece and Italy. Italian sources indicate an unknown but recent origin for Primitivo in Italy. Additionally, Crljenak kaštelanski/Pribidrag/Tribidrag is closely related genetically to many other grapes in Dalmatia, including Plavina, Vranac, and Grk. 40 Maletić, E., I. Pejić, J. Karoglan Kontić, J. Piljac, G.S. Dangl, A. Vokurka, T. Lacombe, N. Mirošević, and C.P. Meredith, “Zinfandel, Dobricic, and Plavac mali: The genetic relationship among three cultivars of the Dalmatian Coast of Croatia”, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 55: 174-180 (2004).

A second group of scientists from Italy proposed broadening the geographical origin of Zinfandel to “Austria, Dalmatia and Hungary” based on comparison with cultivars in those regions. In the process, they identified an additional synonym for Zinfandel, Kratošija, which is an old variety growing in another nearby country, Montenegro. 41 Antonio Calò, Angelo Costacurta, Vesna Maraš, Stefano Meneghetti, and Manna Crespan, “Molecular Correlation of Zinfandel (Primitivo) with Austrian, Croatian, and Hungarian Cultivars and Kratošija, an Additional Synonym”, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59: 2 (2008).

ZINFANDEL AND PRIMITIVO AT FOUNDATION PLANT SERVICES

Early selections in the FPS collection

New Zinfandel importations to California were few between 1850 and 1990. The Zinfandel vines that were in the state early on were shared and exchanged freely up and down the state during that period. The long history of propagation of Zinfandel from non-certified field selections and the uncertain origins of the grape resulted in the existence of relatively few virus-tested clonal selections at FPS prior to 1990. 42 P.S. Verdegaal and C. Rous, “Evaluation of five Zinfandel clones and one Primitivo clone for red wine in the Lodi appellation of California”, In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, J.M. Rantz (ed.), pp. 153-156, American Society for Enology and Viticulture, Davis, CA (1995).

The early Zinfandel selections at Foundation Plant Services originated mainly from the vines that were imported to California in the 1800’s. In 1990, there were four Zinfandel selections registered in the FPS foundation collection – Zinfandel 01A, 02, 03 and 06.

The FPS grapevine collection in 1990 also included Primitivo selections. Primitivo material was imported to Davis after Goheen’s trip to Italy in 1967. One Primitivo selection (Primitivo 03) appeared on the list of registered vines in 1990, and two additional selections were then in quarantine undergoing testing (Primitivo 05 and 06).

Those early FPS selections underwent several clonal comparisons by university scientists and U.C. extension researchers in the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Those projects revealed significant clonal differences between the Zinfandel selections from California and the Primitivo selections from Italy.

Zinfandel 01A and Zinfandel 02 came to FPS in 1961 from two separate vines in a Lodi, California, vineyard owned by Leon Handel. The climate in the Lodi-Woodbridge area is amenable to growing good quality Zinfandel grapes due to the marine influence which permeates the San Joaquin Delta region of the Central Valley. San Joaquin County has led the state in total Zinfandel acreage since the middle of the last century with acreage holding at a consistent ~ 20,000 (including Primitivo). The original plant material from Lodi tested negative for virus. Zinfandel 01A and 02 qualified for the foundation vineyard in 1962.

Zinfandel 06 was propagated from Zinfandel 01A in 1966. The difference between Zinfandel 01A and Zinfandel 06 is that Zinfandel 06 underwent heat treatment for 117 days. Zinfandel 06 first appeared on the registered list in 1967.

Zinfandel 03 came to FPS in 1964 from the Reutz vineyard near Livermore, California, with the label “Reutz #1”. Zinfandel has a long tradition in the Livermore Valley and was an important wine grape variety planted there as far back as 1885. 43 Charles L. Sullivan, 2003, supra at p. 45. Phil Wente of Wente Vineyards reports that the Reutz vineyard was a 40-acre farm owned and farmed by Reinhardt Reutz on Vineyard Avenue just southeast of Pleasanton, California. The vineyard had been planted during Prohibition and, over the years, the grapes were sold to Ruby Hill Winery, Cresta Blanca Winery, Almaden, and Wente Brothers Winery.

Mr. Wente explained: “When U.C. Davis began the process of collecting vines for the foundation vineyard, my grandfather, Ernest Wente, told Harold Olmo that the best Zinfandel in the Livermore Valley was grown in the Reutz Vineyard. A number of other premier varieties were selected from the Livermore Valley as representative of their overall quality, and it was only natural that Zinfandel from this region would be considered as well, based on the quality wines produced over the years from the Reutz Vineyard”. The Reutz vineyard was pulled out in the late 1970s when Mr. Reutz was unable to continue farming it. Zinfandel 03 did not receive heat treatment at FPS and first appeared on the list of registered selections for public distribution in 1965.

Primitivo selections 03, 05 and 06 were imported by Goheen to FPS from Italy. Those Primitivo vines offer another source of genetic diversity for the Zinfandel variety in California. It not known whether or not the FPS Primitivo selections are typical of Italian clones.

Primitivo 03 was obtained by Goheen in 1968 through the Istituto di Patalogia Vegetale in Bari, Italy, the capital city of the Puglia region. The original material had undergone heat treatment at Bari for 59 days. The importation was assigned USDA P.I. number 325796-A-1. After successful completion of testing at FPS, the original material was planted in 1971 in the old FPS foundation vineyard as Primitivo de Gioia 03.

Primitivo de Gioia was an Italian synonym that honored the name of the place in Italy where presence of the Primitivo variety was first recorded. The name of the FPS selection was ultimately changed to simply “Primitivo 03” prior to transfer of the selection to the newly created Brooks South Foundation Vineyard in 1984, when the selection first appeared on the list of registered vines. Dr. Giovanni Martelli explained that the name “Primitivo di Gioia” was the “older” denomination of the variety and can no longer be used, even in Italy, because the European Union has determined that the names of grape cultivars grown in the European Community cannot contain links to geographical locations. The TTB has imposed the same rule in the United States.

Primitivo 05 and 06 are two of four selections that were sent to FPS from Italy in 1987 by Dr. Antonio Calò, of the Istituto Sperimentale Viticoltura (now the Centro di Ricerca per la Viticoltura) in the Veneto region of northeast Italy. The Istituto is an experimental viticultural station established in 1923 in Conegliano and houses an ampelographic collection of more than 2000 grape varieties. 44 Jancis Robinson, 2006, supra at p. 192. Calò donated selections labeled 1 and 2 from the Conegliano collection to FPS at the request of Goheen, who needed additional Primitivo selections to compare to Zinfandel. Both Conegliano selections tested negative for virus and were released in 1994 as Primitivo 05 and 06.

Clonal testing of early selections in California

The publicly-available FPS Zinfandel and Primitivo selections underwent a series of comparisons in California in the years between 1990 and 2003. The studies were conducted at three different sites, using variable experimental protocols for vine management. The results of the clonal studies demonstrated that there can be meaningful differences between the Primitivo and Zinfandel selections in terms of performance in the field and in the character of the wine produced.

Arbuckle

The four FPS Zinfandel selections (Zinfandel 01A, 02, 03 and 06) and Primitivo 03 were tested in a vineyard near Arbuckle, in the Sacramento Valley region of California. The vines were planted in 1988, and data was taken for years 1990-1994. The vines were trained to a T-trellis with bilateral cordon and were spur pruned. 45 J.A. Wolpert, “Performance of Zinfandel and Primitivo clones in a warm climate”, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 47: 124-126 (1996).

The researchers at Arbuckle found few differences in growth and yield parameters among Zinfandel clones. Zinfandel 06 (the heat-treated selection from Zinfandel 01A) was included in the trial to evaluate whether heat-treatment per se had any viticultural significance. Zinfandel 06 did exhibit differences from Zinfandel 01A in pruning and berry weights. More importantly, none of the Zinfandel selections demonstrated the looser clusters and smaller berries exhibited by Primitivo 03.

Lodi

Zinfandel 01A, 02, 03, and 06 and Primitivo 03 were included in another trial in the years 1991-1997 in the San Joaquin Valley near Lodi, California. The vines were grown for White Zinfandel wine production in 1991-1993 and for red Zinfandel wine for the remaining years. The vines were trained to bilateral cordons and spur pruned. The production data was very similar over the years of the experiment in terms of trends and significant differences; the 1994 data was used to report the findings. 46 P.S. Verdegaal and C. Rous, 1995, supra.

In the Lodi trial, there was little or no significant difference among the Zinfandel clones in terms of performance in the field. The primary finding in this trial was a significant difference between Primitivo 03 and the group of Zinfandel clones. The Zinfandel group had higher yield per vine, fewer clusters per vine, higher cluster and berry weights, and later maturity dates than did Primitivo 03. Using the 1994 data (for red wine production), they found that the Zinfandel group had a lower level of soluble solids (° Brix) and later maturity date than did Primitivo 03.

Parlier

The third evaluation occurred in an ongoing research study of grapevines planted in 1997 in a vineyard at the Kearney Agricultural Center, Parlier, in the southern San Joaquin Valley. Included in this study were Zinfandel 01A, 02 and 03 and Primitivo 03, 04 and 05. The vines were grown on their own roots, which is common in Fresno County. They were trained in a bilateral cordon formation and were spur pruned. Unlike the first two trials, these vines were furrow irrigated rather than drip irrigated. The data reported in this study were taken in 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2003. 47 Matthew W. Fidelibus, L.P. Christensen, D.G. Katayama, and P-T. Verdenal, “Performance of Zinfandel and Primitivo Grapevine Selections in the Central San Joaquin Valley, California”. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 56(3): 284-286 (2005).

There were few differences observed between the Zinfandel selections tested in the Kearney trial. However, in the southern San Joaquin Valley (unlike in Arbuckle and Lodi), the Zinfandel selections yielded a similar or lower weight (kg per vine) than the Primitivo selections. Zinfandel selections had fewer clusters per vine, a slightly higher berry weight overall, and lower soluble solids at harvest than Primitivo selections. It was posited that the cause of the differing yield findings exhibited by Primitivo and Zinfandel in Arbuckle/ Lodi versus Kearney could be a rootstock/ scion interaction and/or the value of regional data for making recommendations on planting (e.g., rootstock v. own roots).

Paul Verdegaal, UC Viticulture Advisor in San Joaquin County, commented on the results: “My take on the feasibility of comparing Zinfandel clones across districts [appellations] is you will see differences (due to terroir) but in many cases they will be very subtle and affected by management, especially irrigation. The one “clone” that always seems to stand alone is Primitivo compared to any Zinfandel”. 48 Paul S. Verdegaal, Extension Viticulture Advisor, UCCE San Joaquin County, e-mail to Nancy Sweet on April 23, 2007.

Primitivo 03 was the only registered FPS Primitivo selection included in all three clonal evaluations. In Arbuckle and Lodi, where the vines were grown on rootstock, Primitivo 03 simultaneously produced more clusters per vine and a lower yield than the Zinfandels, which was explained by Primitivo 03 having fewer and smaller berries. In Kearney, the vines were grown on their own roots. Primitivo 03 had a 15% higher yield than the remaining selections despite the fact that (unlike Arbuckle and Lodi) average cluster weight and berries per cluster were similar for all selections. The higher yield for Primitivo 03 was attributed to a statistically significant higher number of clusters per vine for that selection versus all the others.

More importantly, the clonal comparison studies revealed a significant difference between Primitivo and Zinfandel clonal lines that could beneficially impact growers in the warmer districts. The Kearney researchers explained: “one of the major impediments to producing Zinfandel fruit of acceptable quality in the central San Joaquin Valley is Zinfandel’s high susceptibility to sour rot”. 49 Matthew W. Fidelibus et al., 2005, supra. Both Primitivo and Zinfandel have tight clusters and thin skin, which means that there will be some bunch rot with both clonal lines. 50 Olmo and Amerine, Wines & Vines 19(9), supra. However, the Primitivo selections in Kearney suffered substantially less sour rot than the Zinfandel selections, evidencing a lower susceptibility to bunch rot. Within the Primitivo selections themselves, Primitivo 03 was second to Primitivo 06 in the percentage of clusters affected by rot (40% versus 34%).

The Lodi study also assessed the vines for bunch rot and, when rot was measurable during the trial, observed the least amount on Primitivo 03 (versus the Zinfandel selections). The Lodi researchers attributed that finding to Primitivo’s looser clusters, smaller berry size and earlier maturity date.

Soluble solids were measured in all three trials as ° Brix. The Primitivo selection(s) had higher soluble solids (° Brix) at harvest than any of the Zinfandel selections in Kearney, Lodi, and Arbuckle. That result is understandable given the early fruit maturation of the Primitivo variety in general. Primitivo 03 ripened (on average) 7 to 10 days ahead of the Zinfandels in Lodi. However, Primitivo 03 was singled out for special recognition by the Kearney researchers for its combined high yields of fruit (significantly higher than the other Primitivo and Zinfandel selections) along with its high soluble solids. The capstone to those positive findings may be the relative low incidence of sour rot experienced by Primitivo 03.

Primitivo 05 and 06 were formally evaluated only at Kearney. The notable findings for those selections included the following. Primitivo 05 (along with Primitivo 03) had significantly smaller berries than the other selections. Primitivo 06 had the lowest incidence (34%) of clusters affected by sour rot of all the selections. The fruit of Primitivo 06 matured quite early and had a higher juice pH than the others. Primitivo 06 was characterized with Primitivo 03 as the best-performers in the Kearney trial in terms of fruit maturity, yield and bunch rot susceptibility.

The only reported wine tasting trials involving the FPS selections were done in conjunction with the trial in Lodi, California. The red wine tasting panels were done in 1994-1997, with wine lots made by Woodbridge Winery. In 1994, the wines were divided by the tasters into two groups. Zinfandel 03, Primitivo 03 and Zinfandel 06 (in order of preference) were in the top group, with more dense color, better hue, and more black cherry and berry flavors. 51 P.S. Verdegaal and C. Rous, 1995, supra. It was considered surprising that two of the heavier yielding clones – Zinfandel 03 and 06 – were in the top group.

There was an issue in the 1995 data about not thinning the vines adequately. For that crop, the tasters preferred Zinfandel 03, 06 and 02 to an overcropped Primitivo 03 and Zinfandel 01A. In 1996, the vines were thinned and taster preferences split into three groups (in order of preference): (1) Primitivo 03; (2) Zinfandel 03, 06, and 02; and (3) Zinfandel 01A.

The evidence from the three Central Valley trials showed that the Primitivo and Zinfandel “clones” performed in a substantially different fashion in Arbuckle, Lodi and Kearney. In all sites, the Primitivo fruit matured earlier than did the Zinfandel grapes. The name of the Primitivo variety comes from the Latin primus, which means “first”. The Primitivo grape variety is “early at all stages of its physiologic development compared to other vine varieties”.

52 Antonio Calò, Attilio Scienza, and Angelo Coastacurta, Vitigni d’ Italia, pp. 632-633, Calderini edaricole. Bologna, Italia (2001). (in Italian).

Heritage Zinfandel

The most significant “clonal difference” exhibited by the FPS Zinfandel and Primitivo selections in the studies in the Central Valley could be the finding related to bunch rot. The Primitivo clusters are structured in a way that results in less rot, which is particularly important to growers in the warm areas of the California interior.

THE SEARCH FOR NEW HERITAGE CLONES AT FPS

A head trained “old vine” Zinfandel in Paso Robles, CA

Director Deborah Golino focused on collection of additional heritage grapevine clones for FPS beginning in the mid-1990’s. Several heritage Zinfandel clones were donated to the FPS public grapevine collection in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, including many donations from very old California vines. Old-vine sources for Zinfandel plant material are sought after by wine makers. The theory is that grapes from very old vines maintained in the traditional head-trained style for vine balance produce smaller berries and lower crop yields with more concentrated flavors. 53 Charles L. Sullivan, 2003, supra at p. 138.

Morisoli Heritage Vineyard

Gary Morisoli (Morisoli Vineyards and Elyse Winery) donated cuttings representing nine varieties to FPS in 2002 from the Napa Morisoli Heritage Vineyard, which is thought to have been originally planted in the late 1800s. The vineyard was predominately Zinfandel but, as is common in older California vineyards, there were other varieties present, including both wine and table grapes. Morisoli’s grandfather (born 1902) said that, as a teenager, he began to replace some of the old vines in the vineyard as they died. Morisoli suspects that some of the original plantings remained in the vineyard. Some of the Zinfandel has been a fixture in the vineyard for over 100 years. 54 “2002 Introductions for the Future Public Collection”, FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2002, p. 3.

Ampelographer Jean-Michel Boursiquot, then the Director of ENTAV in France, UC Viticulture Extension Specialist Jim Wolpert, and FPS Director Deborah Golino visited the Morisoli Vineyard in 2001 to examine the vines. About 1 ¼ acres of the vineyard remained at that time. Boursiquot was able to identify nine varieties of interest to FPS and the public heritage clone program, and the vines were marked with the correct variety names. In December of that year, Golino collected dormant wood from those mature vines for testing and treatment at FPS.

Zinfandel 48.1 is one of the heritage clones from the Morisoli Heritage Vineyard donated to the FPS public collection. The original material tested positive for virus and underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy in 2007. The treated material was released in 2014 after successful completion of testing.

Inglenook Vineyard

Another heritage Zinfandel arrived at FPS at the same time as the Morisoli heritage selection. The source of the second heritage selection was the Gate Vineyard located near the Niebaum château on the Inglenook property in Rutherford, California. The Gate vineyard was planted in 1996 using Zinfandel material from Gary Morisoli’s vineyard across Niebaum Lane, as well as Zinfandel from the Werle vineyard near the Silverado Trail. The original plant material submitted to FPS tested positive for numerous viruses and underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy. The treated material was released as Zinfandel 49.1 in 2014.

Howell Mountain

One of the heritage clones added most recently to the FPS collection is the “Black Sears Zinfandel” clone, which came from Black Sears Winery in Napa in 2008. The source vineyard for the cuttings was Black Sears on Howell Mountain. The vineyards on Howell Mountain at 1800 feet on the Vaca Mountain Range are home to some of the oldest existing Zinfandel vines in Napa. The sponsor of this clone indicates that there is a notable peppery component to the wine made from the clone. Zinfandel 47.1 completed testing at FPS and qualified for the foundation vineyard in 2013.

Deaver clone, Amador County

The Sierra Foothills is the wine region in "Gold Rush Country" in California, on the western edge of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. 55 Jancis Robinson, The Oxford Companion to Wine (Oxford University Press, 3d ed., Oxford, England, 2006), p.630 Amador County is one of the counties in the region and is also where the California Shenandoah Valley AVA is located. Zinfandel has been grown in the Sierra Foothills since the 19th century, although the region did not become famous for its old vine Zinfandel until much later. 56 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 48-49 (University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London (2003).

The Deaver Vineyards are part of the oldest established vineyard in the Shenandoah Valley in Amador County. The first vines on the Deaver-Davis Ranch were planted around 1854. The family began to plant Zinfandel after 1870. Ken Deaver continued to develop the property after 1947 and began selling grapes to home winemakers and later commercial wineries. He bottled his first Zinfandel with the trademark label in 1986. www.deavervineyards.com.

Sacramento wine merchant Darrell Corti discovered the old Zinfandel vines of the Shenandoah Valley in the 1960's, in particular the vines of the Deaver Ranch. Corti contacted Bob Trinchero about the Deaver grapes in 1968 and the first vintage of the "great Corti/Sutter Home Zinfandels" was produced. 57 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 111-112 (University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London (2003). The label for the "Corti Brothers Reserve Selection Zinfandel, Amador County, Vintage 1968" reflected that the wine was produced by Sutter Home Winery from grapes grown on the K. Deaver Ranch in the Shenandoah Valley just north of Plymouth, Amador County. 58 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 111-112 (University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London (2003).

Zinfandel FPS 50.1 was donated to the public grapevine collection at Foundation Plant Services in 2014 by Stan Grant of Progressive Viticulture. The material is the "Deaver clone" of Zinfandel from Amador County. Fresh green growing shoots of the clone were sent to FPS to undergo disease therapy and testing. The selection qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2018.

Duarte Nursery

Duarte Nursery in Hughson, California, donated three Zinfandel selections to the FPS public grapevine collection in 2009. Zinfandel 45.1 is the “Zinfandel Hambrecht” clone. Zinfandel 46.1 is the “Zinfandel Mendocino” clone. Zinfandel 35 was named "Zinfandel Shenandoah" and was collected in Amador County. The Sierra Foothill region, in particular Amador County’s Shenandoah Valley, has produced quality Zinfandel wines since the 1970’s. 59 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel, A History of a Grape and its Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2003), page 122.

Proprietary Heritage Zinfandel clones

Bob Dempel

Zinfandel 08 is a proprietary selection owned by Bob Dempel of Dempel Farming Co. in Santa Rosa and entered the FPS testing process in 1996. The source of the plant material was 100-year-old Zinfandel vines planted on Bisordi Lane in Fulton, Sonoma County. Dempel states that the clone is known for its small clusters and berry size. Wine produced from Zinfandel 08 berries by Paradise Ridge Winery in Santa Rosa, California, in 2003 exhibited deep color, a rich texture and brambly berry, spice and pepper flavors. 60 Tina Vierra, “Old Vine Zinfandel clone tested and available for planting”, Practical Winery & Vineyard, p. 80 (May/June 2005).

Some of the original material submitted to FPS tested negative for virus and qualified for the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 1998. Zinfandel 08 was removed from that vineyard in 2006 due to virus; however, mother vines in private increase blocks remain registered sources of California certified planting stock.

Zinfandel 29 was propagated by microshoot tip tissue culture therapy from Zinfandel 08 vines. Dempel has named this subclone of Zinfandel 08 the Baldocchi Zinfandel clone in honor of his friend Dewey Baldocchi, a wine maker and pioneer in the Sonoma County grape industry. 61 Millie Howie, “Romancing the Clone”, Wines & Vines, p. 39 (June 1999).

Nova Zinfandel

Zinfandel 13 is a proprietary selection owned by Novavine Nursery in Santa Rosa, California. The original plant material came to FPS in 1999 from an old vine Zinfandel vineyard owned by Milton and Ellen Heath. The vines of the Nova Zinfandel clone are grown in sandy loam soil on the Kelseyville benches (1300-2000 feet) at the base of Mount Konocti in Lake County. Jim Smith, who manages the source vineyard in Lake County, explained: “The vines [of this clone] yield a versatile grape that is very ‘fruit forward’ with a nose that ‘jumps out of the glass’. Spiciness can be dictated by an open canopy (very fruity) or an extra-shaded canopy (heavy peppery characteristics).” 62 Jim Smith, personal communication to author (2007). Five wineries – Wild Hog, X Winery, DeLoach, Hall Crest, Jelly Jar - have produced unique and very different wines composed almost solely of fruit from this clone.

Kendall Jackson

Zinfandel 16 is an old-vine Zinfandel that is a proprietary selection owned by Kendall-Jackson for its Hartford Court label. The original plant material came to FPS in 1997 from a vineyard located on Wood Road in Forestville, Sonoma County, approximately 15 miles from the Pacific Coast. The vineyard was originally planted in the early 1900’s, and the vines are head-trained on St. George rootstock. Don Hartford, owner of the Wood Road vineyard, notes that the clone seems to do well in the cool Russian River Valley climate. It gets fully ripe while maintaining an acid balance that promotes a bright fruit character as well as good weight and texture.

Kendall-Jackson maintains another planting of this same Hartford clone on shallow gravelly (Huichica) clay loam soil atop a hill overlooking the Santa Rosa plain at Windsor, Sonoma County. Under cool, sometimes humid conditions, and shallow clay loam soil on a hillside, this Zinfandel clone is reported to ripen in a timely manner and produce concentrated flavors. Zinfandel 16 was produced by microshoot tip tissue culture propagation and was released in 2006.

CALIFORNIA ZINFANDEL HERITAGE VINEYARD PROJECT

The Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project was a collaborative effort initiated in the 1990’s to preserve germplasm from historic California Zinfandel clones for the benefit of the public. Zinfandel Advocates and Producers (ZAP), a trade association composed of producers and consumers of Zinfandel wine, partnered with the Department of Viticulture & Enology, U.C. Davis, and the U.C. Cooperative Extension to collect and preserve old vine Zinfandel selections from vineyards throughout the State of California.

The effort was initially directed by U.C. Davis Extension Viticulture Specialist Dr. James Wolpert. Wolpert explained the impetus for the project as follows. Some winemakers complained in the past that the four Zinfandel “clones” offered at FPS were not high-quality selections. The FPS selections were criticized as having large, tight clusters and large berries, that led to bunch rot at relatively low ripeness. The resulting wines were characterized as having low intensity of varietal character, suitable for “white” (White Zinfandel) but not for “fine red” wine. 63 James A. Wolpert & Michael Anderson, “AVF-funded research – Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Update”, American Vineyard Foundation, July/August 2003; Zinfandel Advocates & Producers, undated publication, The Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project, The Zinfandel Chronicles, page 1.

The Project team took “Zinfandel safaris” to more than 100 vineyards throughout the state of California

The initial assignment for the project team in 1995 was to collect budwood from certain well-known California Zinfandel vines that were at least 60 years old. Wolpert and his colleagues began taking “Zinfandel safaris” to more than 100 vineyards. Those colleagues included U.C. Viticulture Extension Specialists Amand Kasimatis (Emeritus), Rhonda Smith, Ed Weber, Paul Verdegaal, Donna Hirschfelt, Janel Caprile, Jack Foott and Glenn McGourty. The team sought to include as wide a geographic range as possible; when complete, the collection represented fourteen California counties from San Bernardino to Mendocino (Sonoma, Mendocino, Napa, Contra Costa, San Luis Obispo, San Joaquin, Lake, Amador, El Dorado, Calaveras, Alameda, Santa Cruz, San Bernardino, and Riverside). Additional parameters of the project specified vines with loose clusters and small berries and vines that were free of “red leaf” symptoms in the fall.

The cooperators for the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project chose to maintain confidentiality of the original vineyard sources for the heritage clones. The promises of confidentiality to the owners of the source vineyards encouraged their participation in the project. Additionally, the project team did not want undue influence placed on association with a place name or winery over actual performance and wine research results during the trials. The identities of all but five of the heritage Zinfandel selections remain confidential as of 2018.

Phase I screening

Phase I of the research for the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project began at UC’s Oakville Experiment Station in Napa in 1995. The intent of the phase I research was to do initial screening of the heritage clones and compare them to the existing FPS selections. In addition to the initial 63 heritage clones collected by the team, FPS selections Zinfandel 01A, 02 and 03 and Primitivo 03, 05 and 06 were planted in the block.

The selections were field grafted onto St. George rootstock and were head trained and spur pruned in the goblet shape from the 19th century. The vines were screened for disease by visual examination and PCR testing. Although that stage of the research did not include replicated trials, data describing juice chemistry as well as vegetative and reproductive growth and other viticultural characteristics were collected from each of the selections for five years. 64 Anderson, M.M., R.J. Smith, E.A. Weber, G.T. McGourty and P.A. Verdegaal, D.J. Hirschfelt, A.N. Kasimatis, J.A. Wolpert. 1999. Comparison of Yield Components, Cluster Measurements and Fruit Composition of Sixty-three Zinfandel Clones and Field Selections, Unpublished.

In the initial screening phase, the researchers were looking for vines that performed uniquely and consistently over time relative to other selections. The observations and data showed that Primitivo matured (° Brix) sooner than Zinfandel and had lighter mean berry and cluster weights than the Zinfandels. Primitivo clusters continued to be structured differently (looser, less compact) even when grown in the climate and topography of a county like Napa. 65 Anderson et al., supra, 1999, unpublished.

The Primitivo selections all had values of yield, cluster weight, berry weight, and berries per cluster that were equal to or lower than the mean for all selections. Primitivo FPS 05 had both the lightest clusters and smallest berries in the entire group. Although the Primitivo selections produced more clusters per vine, they had lighter yields attributable to smaller berries and fewer berries per cluster than the Zinfandel selections. Those Primitivo berries also ripened sooner than the Zinfandel selections.

Wolpert commented at the conclusion of phase I: “The range shown in growth and yield parameters fuels our hope that there is significant variability within the Zinfandel heritage selections.” 66 Wolpert and Anderson, 2003, supra.

The project researchers evaluated the data for the issue of whether the reputation of FPS Zinfandel selections as “large-berried, large-clustered, high-yielding selections” was justified. The data showed that on no parameter did the FPS selections set the high or low value for the vineyard. The researchers were able to conclude that the FPS [Zinfandel] selections were clustered around the mean of the range of performance in yield parameters for all clones in the trial. 67 Wolpert and Anderson, 2003, supra.

FPS participation in the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project

Foundation Plant Services donated disease testing and virus-elimination therapy services to the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project. FPS was able to donate services as a result of a reserve created by user fees from the nurseries that participate in the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program. Budwood from 20 of the heritage clones was sent to FPS beginning in 1991 to commence the certification process. Code numbers were used to maintain the confidentiality of the source vineyards. The selections ultimately arrived at FPS in three groups – 1991, 1997, and 2001 – and were screened for virus.

Phase II replicated trials

After five years of initial screening in phase I, 20 heritage Zinfandel clones were selected and moved to phase II of the project in 2001. Funds to plant, maintain and take data from the California Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard block were provided by the Zinfandel Advocates and Producers (ZAP). 68 Penn M., M. Anderson, J. Wolpert and A. Walker. 2015. “Search for Zinfandel genetic diversity”, Practical Winery & Vineyard, p. 65 (July 2015).

Phase II of the project consisted of replicated trials at the Oakville Experiment Station. The twenty heritage participants were chosen using two criteria: (1) the selections would be virus tested at FPS; and (2) each of the selections had a unique vineyard source (no duplicates).

The phase II replicated trial also allowed for more meaningful and thorough data collection. Five blocks on a total of two acres were each planted with all 20 heritage selections plus two Primitivo selections (FPS 03 and 06) and two FPS Zinfandel selections (FPS 02 and 03). In the replicated trial, the plot size and vine number per selection were increased to make larger, more representative wine lots. The vines were planted at a spacing of 6 x 8 and were head-trained and spur-pruned. Drip irrigation was used. 69 Penn et al., supra, 2015. Data was taken from this trial from 2005-2012. Wines were made and evaluated.

“The final eight”

In 2013, a group of winemakers from ZAP and researchers tasted and ranked wines made from the selections in the replicated trials. Data from the replicated trials were examined at that time. Six heritage selections were chosen as distinctive and were advanced to intensive viticultural and fruit analysis in 2013 and 2014. Additionally, Zinfandel FPS 02 and Primitivo FPS 03 were included in the intensive analysis. 70 Penn et al., supra, 2015, at p. 68.

The researchers in 2013 were particularly focused on whether any genetic variation was exhibited in selections of California Heritage Zinfandel. The 2013 data showed significant differences in some respects between Primitivo and Zinfandel; Primitivo showed lower cluster weights, fewer berries per cluster, fewer seeds per berry and earlier maturity than Zinfandel. It is interesting that the Primitivo clone from Italy (in contrast to the Zinfandel clones that developed for many years in California) was so distinctive since the material was almost surely from a different clonal source than the material in California.

The picture was less clear regarding the differences among the Zinfandel selections. The researchers concluded the heritage selections and Zinfandel FPS 02 were “phenotypically identical in their expression when examined in a single vineyard.” 71 Penn et al., supra, 2015, at p. 69.

UC Davis grape breeder Dr. Andy Walker, who now manages the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project, indicated that the heritage vineyard is helping researchers understand how berry number and size and seed tannins affect wine quality. The study has shown that there is little genetic difference in the morphology of the Zinfandel vines and taste of the wines that they produce. For now, Walker believes that environmental factors (terroir) affect vine and wine expression more than clonal differences. 72 Mike Dunne, “Vintners in pursuit of Zin mastery”, Sacramento Bee, January 8, 2014, p. D3.

Blind tasting of the final eight selections in 2014

UC Davis and ZAP staged a blind tasting of wines in fall, 2014, made from the eight clones/selections that were advanced for intense scrutiny in 2013. Forty participants attended at the Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science on the Davis campus. The wines were identified by code number, and the identity of the source vineyards was not revealed. Confidentiality was deemed important to avoid undue influence on place or winery name and to judge the clones based on the actual performance data and wine research results in the replicated trials. Additionally, some of the source vineyards requested confidentiality.

An informal vote was conducted at the conclusion of the tasting. The overall favorite of the tasting was the only Primitivo in the tasting, Primitivo FPS 03 from Bari, Italy. The wine was denser in color and “more lush in fruit” than the others. 73 Dunne, supra, 2014, p. D3.

The data accumulated during the trials revealed that Primitivo matured earlier than the Zinfandel selections and the Primitivo berries were smaller. Primitivo yielded wine with more color, higher alcohol and riper flavor. 74 Penn et al., supra, 2015. Dr. Walker explained that Primitivo always came out on top because it ripened earlier and bit more evenly. 75 Walker, M. Andrew, personal communication with author, email dated August 23, 2018.

The wine that finished second in the tasting was made from the FPS selection Zinfandel 02 (from the Handel vineyard in Lodi in 1961). A news report at the time stated that FPS 02 was also known as “the UC Davis clone”, the “White Zinfandel clone” or the “often-maligned Clone 30 strain of Zinfandel”. For purposes of the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project, Zinfandel FPS 02 had been disguised with the project code name “Clone 30”. The news report indicated that FPS 02 was characterized as the “White Zinfandel clone” due to its reputation for productivity and adaptability. It was considered “surprising” that the wine that finished a close second to Primitivo was made from Zinfandel FPS 02. The wine at the tasting was described in the news report as “sleek, crisp and readily accessible”. 76 Dunne, supra, 2014, at p. D3.

The informal results for Zinfandel FPS 02 at the blind tasting may not have been so surprising. The research in the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project showed that there was little genetic difference in the morphology of the Zinfandel vines planted together in one vineyard. In contrast, production levels vary when vines are planted throughout the state based on such things as crop level management, irrigation and climate. Vineyard yields destined for white Zinfandel wine production are higher than those cultivated for red wine production since lower sugar levels are acceptable for the former. Supplemental irrigation, pruning and trellising and cluster thinning to manage crop color and ripeness influence the quality and amount of yield. Researchers from the university concluded in 2003 that the lack of popularity of the older registered (FPS) selections could be due to “perceived problems in site and vine management practices”. 77 Rhonda J. Smith, “Zinfandel”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, ed. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert, University of California, Agriculture & Natural Resources, Publication 3419, page 163 (2003).

Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project clones at FPS

Twenty Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project clones were released to the public by FPS under code numbers in spring, 2009. It was perceived from comments by customers that sales of the clones were anemic primarily because of the anonymity factor as to source vineyard. The apparent lack of current interest in the heritage Zinfandel material (as shown by FPS sales records) is indicative of the high value placed by the wine grape community on the concept of provenance. FPS Director Golino states that grape growers and wine makers place a high value on the story of their vineyards and that story is often associated with the history of the plant material.

The FPS foundation vineyard contains 27 unique Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project clones in 2018. Most of the heritage clones have undergone microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS to qualify them for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard.

The identity of the source vineyards for the Heritage Project clones at FPS remains confidential for 22 of the 27 selections. ZAP and U.C. Davis jointly revealed the origin of four of the heritage clones by press release issued on December 03, 2014. Each of the four clones represents a unique historic old vine source and is geographically diverse from the other clones. The four clones whose identity was revealed by project coordinators in 2014 were:

Zinfandel FPS 24 and 24.1 (Heritage Project clone 31) is from Lytton Springs north of Healdsburg in Sonoma County. The property was originally developed around 1860 as a resort by Captain W.H. Litton. Ridge Vineyards now owns the 69-acre vineyard on the property planted mostly to Zinfandel. The heritage clone (clone 31) for the Heritage Zinfandel Project was harvested from one of the 115-year-old vines.

Zinfandel FPS 25 and 25.1 (Heritage Project clone 38) was collected from the R.W. Moore Vineyard planted by seafarer Pleasant Ashley Stevens in 1905 in the Coombsville Appellation in Napa Valley. The 10-acre vineyard of head trained vines has produced Zinfandel for more than 100 years.

Zinfandel FPS 10 (Heritage Project clone 10) originated from a vineyard planted by the Reiner family between 1913 and 1919 in the gravely clay loam Tuscan Red Hill series soils of the Dry Creek bench in Sonoma County. The vineyard was purchased by the Teldeschi family in 1946 and has been farmed by them since then. A version of Zinfandel 10 produced by microshoot tip tissue culture therapy is known as Zinfandel FPS 15.1.

Zinfandel FPS 26 and 26.1 (Heritage Project clone 44) is from Zeni Ranch which is located on a narrow ridge top on the divide between the Garcia and Gualala River watersheds in Mendocino County. This selection was harvested from a vine in the original part of the vineyard on the property. The three acres of head-trained, dry-farmed gnarly vines were planted in the 1880’s and feature Zinfandel and other varieties. Eduino Zeni purchased the property and named it Zeni Ranch in 1919.

Monte Bello vineyards in the Santa Cruz Mountains

The identity of a fifth Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project clone was revealed by Ridge Vineyards with the permission of the prior owners of the property. Zinfandel FPS 56 and 56.1 was collected as part of the Zinfandel Heritage Project and was initially known anonymously as California “Heritage Zinfandel number 80 from Santa Clara”. The owner of the vineyard where the selection was collected gave permission to reveal the identity of the original source vineyard. Zinfandel 56 was collected from a vineyard at the historic Picchetti Ranch on Montebello Road in the Santa Cruz Mountains of California. The Picchetti vineyard was planted in the late 1800's on Montebello Road.

Zinfandel FPS 51.1 was probably sourced from the same Picchetti Estate Vineyard as was Zinfandel 56. Zinfandel 51.1 was donated to the FPS public grapevine collection in 2014 by Larry Hyde, a well-respected grape grower and winemaker in the Carneros region of Napa County. The vineyard manager at the Picchetti Estate gave Hyde permission to take cuttings. Hyde planted the selection in his vineyard in Carneros, from which he collected the material to donate to FPS. The material underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy and qualifed for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2018.

FPS Director Golino explained that the Zinfandel Heritage Vineyard Project had value in several respects. An important collection of Zinfandel clones from historic vineyards throughout California has been preserved and is available as virus-tested clean stock from the grape collection at Foundation Plant Services. The data in the study on the performance of the Primitivo clone from Italy suggests that the Croatian Zinfandel clones in the FPS collection could possibly add some diversity to California vineyards.

CROATIAN ZINFANDEL CLONES AT FPS

After the Croatian vines were identified in 2001 as the ancestral line of California’s Zinfandel grape, Ridge Vineyards, scientists at the University of Zagreb in Croatia and FPS negotiated an international exchange of plant material to bring the Croatian “Zinfandel” clones to California. Crljenak kaštelanski and Pribidrag clones were imported to the United States in 2002 and 2005, respectively. In turn, FPS selections of both Zinfandel and Primitivo were returned to Croatia, where they were compared to indigenous clones for vineyard and winemaking performance.

Ridge Vineyards and the Croatian scientists who discovered the Crljenak and Pribidrag vines hope that testing under experimental conditions will show that the Croatian clonal line possesses some valuable qualities that could enrich California Zinfandel wines. David Gates, Vice-President of Ridge Vineyards, stated: “The genetic variability in these selections from Croatia will hopefully add a bit more complexity and diversity to California Zinfandel. It will be fun to see in the coming years just how that genetic variability will express itself, viticulturally and in the wines made from these grapes”.

Crljenak kastelanski vine in Croatia

The Crljenak kaštelanski vines came to FPS from Kaštel Novi, Croatia, in 2002. The original plant material suffered from virus and underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2008. The treated material was initially released in 2012 as Crljenak kaštelanski FPS 01.1. The name of the selection was changed to Zinfandel FPS 42.1 in 2013 to reflect the preferred name for the cultivar in the United States and to facilitate marketing of the material.

Three Pribidrag selections from Svinišće and Marušići, Croatia, were imported to FPS in 2005. The two Pribidrag clones from Svinišće were VV-079 and VV-101. Clone VV-079 reportedly has loose, cylindrical clusters, and the wine exhibits a crisp aromatic flavor. Clone VV-101 has small, short clusters with larger berries. Both clones underwent microshoot tip culture therapy at FPS and successfully completed testing in 2011 and 2012. They were initially released as Pribidrag FPS 01 and 02. The names were changed in 2012 to Zinfandel FPS 43.1 (clone VV-079, formerly Pribidrag 01) and Zinfandel FPS 44.1 (clone VV-101, formerly Pribidrag 02).

The third Pribidrag clone is VV-134 from Marušići, Croatia. Clone VV-134 has loose clusters, and the wine has intense fruity aromatics. The original material underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2014 but has yet to qualify for the foundation vineyard in 2018. 78 Goran Zdunić and Josh Chase, “New Croatian Winegrape Varieties at FPS”, FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2012, p. 8.

Clonal testing in Croatia

Six Crljenak kaštelanski selections (clonal lines from a single vine), two Primitivo selections and one Zinfandel (Zinfandel FPS 01A) were evaluated in Split, Croatia, over two growing periods in 2008 and 2009. Vine yield components and fruit composition were measured. The researchers found significant differences among the nine selections for everything except cluster number per vine and Ravaz index (crop load, yield/pruning weight). Zinfandel 01A had the highest yield (1.80 kg/vine), better vegetative growth and the highest number of berries per cluster and berry weight. One of the Crljenak vines had the lowest yield (0.83 kg/vine). The Crljenak and Primitivo selections had similar fruit composition, including the highest sugars and pH values at harvest, and matured earlier than the Zinfandel. The researchers concluded that the results showed “a significant genetic variability between the investigated selections and justify further efforts in clonal selections for Crljenak kaštelanski”. 79 G. Zdunić, S. Šimon, N. Malenica, I. Budić-Leto, E. Maletić, J. Karolgan Kontić and I. Pejić, “Intravarietal Variability of ‘Crljenak kaštelanski’ and Its Relationship with ‘Zinfandel’ and ‘Primitivo’ Selections”, Proc. Xth Intl. Conf. on Grapevine Breeding and Genetics, pp. 573-575, Eds.: B.I. Reisch and J. Londo, Acta Hort. 1046, ISHS 2014.

A mother block containing virus-tested Zinfandel, Primitivo and Crljenak/Tribidrag selections was established by the Institute for Adriatic Crops in Split, Croatia in May, 2014. The Pribrag and Crljenak clones that underwent testing and treatment at FPS (Zinfandel FPS 42, 43, and 44) are included in that block, along with Primitivo FPS 03 and 06 and three heritage Zinfandel clones from the FPS collection. The virus-tested clonal material will continue to be studied and evaluated there and will be used as the basis of a clean plant collection for Croatia.

The discovery of the Croatian clones Crljenak kaštelanski and Pribidrag could have a significant impact on the genetic diversity of Zinfandel clonal material in California. The variety known in California as Zinfandel and in Croatia in 2018 by the prime name Tribidrag has been cultivated in central Europe for centuries. Therefore, it would be reasonable to expect the greatest diversity of clonal variation to exist in the region around Croatia, Hungary and perhaps Austria. Clonal testing in Croatia and California is expected to reveal any unique qualities the Croatian clones offer to wine-makers.

Drs. Maletić and Pejić at the ZPCT mother block in Split in 2014

ADDITIONAL CROATIAN WINEGRAPE VARIETIES AT FPS

Wine has been made in the region now known as Croatia since ancient times. The discovery of the Tribidrag (Zinfandel) vines has revitalized the wine industry in that country. That industry is based on fewer than 15 native varieties. Several significant native Croatian varieties were imported to FPS in 2010 and are now a part of the FPS foundation grapevine collection. Many of the native Croatian varieties are genetically related to Zinfandel.

Plavac mali