Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis -

July, 2018

© 2018 Regents of the University of California

With special thanks to Dr. Peter Cousins, E&J Gallo

Pinot: A Treasure House of Clonal Riches

University of California scientists and viticulturists believed early on that Pinot noir was not a practical choice due to the warm climate in the state and low production levels associated with the variety. Pinot varieties were nevertheless included in experiment station and viticulture department vineyards when the University initiated its grape and wine evaluation program in the 19th century. By the 1970’s, there was strong industry interest in Pinot noir in the cooler Winkler regions of California as well as in Oregon and a growing perception that many distinct clones had evolved. The Pinot varieties at Foundation Plant Services’ Davis vineyards in 2017 have the largest number of active selections and number of vines - the Pinot noir number alone exceeds that of Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon or Zinfandel. 1 The number of active groups (individual selections) for the most popular grape varieties at FPS in 2017 are: Pinot noir (225), Chardonnay (178), Cabernet Sauvignon (163), and Zinfandel (108). Active groups for other Pinot varieties are: Pinot gris (28), Pinot blanc (18), Pinot Meunier (9), Meunier (1), Pinot nero (2) and Pinot noir Precoce (1). There are 885 vines for Pinot varieties in the FPS foundation vineyards. The next highest number of vines is Chardonnay with 572.

Pinot noir is the most important of the Pinot group and is planted in some of the coolest viticultural regions in the world. The variety requires fewer degree days (1,150) to ripen sufficiently and can mature in a short growing season. Pinot noir is widely grown in France, Germany, Italy, Australia, South Africa, and South America. In Switzerland, the variety produces fruity red wines. Pinot noir is well adapted to the high latitudes in Burgundy and Champagne in France. 2 Smith, R.J. Pinot noir. Wine Grape Varieties in California, eds. L.P. Christensen, N.K. Dokoozlian, M.A. Walker, and J.A. Wolpert, Publication 3419, Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California (2003), pp. 107-111.

The variety is also grown across North America, with plantings in the northeastern United States, in Oregon, Washington State, and California, and in British Columbia and Ontario, Canada. 3 Anderson M., R. Smith, M. A. Williams, and J. A. Wolpert. Viticultural Evaluation of French and California Pinot noir Clones Grown for Production of Sparkling Wine, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59(2): 188-193 (2008). Pinot noir is most closely associated in the United States with the State of Oregon. Oregon Wine Board figures show that 17,452 acres of Pinot noir were planted in the state in 2015. Pinot gris is a distant second with 3,600 acres. 60 to 80 % of the wine production in the State of Oregon is attributable to Pinot noir. 4 Southern Oregon University Research Center, 2015 Oregon Vineyard and Winery Census Report (September 2016). http://industry.oregonwine.org/wp-content/uploads/2015-Oregon-Vineyard-and-Winery-Census-September-2016.pdf

In California, Pinot noir succeeds in locations with a coastal influence (fog, breeze and coolness from ocean water), such as the Russian River (Sonoma), Carneros (Napa), and Santa Maria (south Coast). None of the Pinot varieties was named as a principal wine variety in the state in statistics prepared by the USDA and California Crop & Livestock Reporting Service in 1942, 1945 and 1952. 5 Olmo H.P. Our Principal Wine Grape Varieties Present and Future. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 5: 18-20 (1954). UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 55: 45, box 65: 36; box 55: 18. When Harold Olmo travelled to Europe in 1951 to retrieve wine grape varieties for FPMS, there were approximately 300 acres of Pinot noir, 100 acres of Gamay Beaujolais and 200 acres of Pinot blanc in California. 6 Olmo, H.P. Handout for Viticulture 105 class, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 55: 45. Pinot noir acreage increased by 245% (to 1,009 acres total) in the Central Coast counties between 1952 and 1963-64. Pinot blanc acreage increased 107% (to 598 acres total). 7 Winkler A.J. Varietal Wine Grapes on the Central Coast Counties (Alameda, Mendocino, Monterey, Napa, San Benito, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, and Sonoma) 1963. UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, 56: 46.

A significant expansion in Pinot noir plantings and winemaking in California began around 1981. The movie Sideways debuted in 2005, focusing on the Pinot noir wine industry on the Central Coast of California and increasing the public’s awareness of the wine. At the time of the debut, there were 24,442 acres of Pinot noir grapes planted in California. By 2016, total plantings of Pinot noir increased to 44,578 acres, making it the third most planted red wine grape after Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel. Pinot gris plantings approached 17,000 acres in 2016. 8 California Department of Food & Agriculture (CDFA). California Grape Acreage Report, 2016 Crop, pages 9-10, April 20, 2017. USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, www.nass.usda.gov/ca.

John Winthrop Haeger relates the history of Pinot noir in Europe and North America in detail in his book North American PINOT NOIR. 9 Haeger, J.W. North American Pinot Noir. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California (2004). He details the many regions where the variety has been tried and thrived in winemaking. He offers profiles of six dozen Pinot noir producers, presenting a comprehensive picture of Pinot production in the United States and Canada. Much information can be gleaned from his book, particularly about the wine qualities of the Pinot noir variety.

Pinot is an ancient variety of unknown origin. The variety is strongly associated with the Burgundy region in northeastern France. Roman authors in the first century described a vine that was probably Pinot present in Burgundy at the time of the Roman conquest. A Burgundian document from the 14th century mentioned the names Pinot fin, Franc Pinot, and Noirien. 10 Robinson J., J. Harding and J. Vouillamoz. Wine Grapes. HarperCollins, New York, pp. 805-806, 811 (2012). Pinot noir produces highly-regarded wines from that region associated with vineyards named Romanée-Conti, Chambertin, and Pommard, all from grapes harvested in the Côte d’Or. 11 Galet, P. Grape Varieties and Rootstock Varieties. OENOPLURIMÉDIA sarl, CHAINTRÉ, France (1998), pp. 112-113. Pinot was also grown in other parts of Europe in the late Middle Ages. 12 Bowers J., J-M. Boursiquot, P. This, K. Chieu, H. Johansson, and C. Meredith.Historical Genetics: The Parentage of Chardonnay, Gamay, and other Wine Grapes of Northeastern France, Science 285: 1562-1564 (3 September 1999).

Pinot appears to be a genetically unstable variety with several forms, including Pinot noir, Pinot gris, Pinot blanc, Pinot Meunier, Pinot noir Précoce and Pinot Teinturier. Its original and most common form is Pinot noir. Some authorities refer to these forms as a “family of varieties” and consider each form to be a distinct variety. Others conclude that it is misleading to characterize the group as a “family of varieties”, because all the forms are mutations that appeared within an initial variety, Pinot, and share the same genetic profile. In the latter analysis, the variations within the Pinot variety would be classified as clones or sub-types. 13 Robinson J. et al. Wine Grapes, supra at pp. 805-806.

Although variation in grape clones can be caused in part by systemic viruses, some of the diversity within Pinot noir has been demonstrated to have a genetic basis as a result of a point mutation or the accumulation of mutations over time. 14 Riaz S., K.E. Garrison, G.S. Dangl, J-M. Boursiquot and C.P. Meredith. Genetic Divergence and Chimerism within Ancient Asexually Propagated Winegrape Cultivars. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 127(4): 508-514 (2002). The identifiable clones or sub-types of the Pinot variety have been stabilized over time by asexual propagation to preserve their distinctive viticultural or enological features. Mutations have resulted in visibly detectable differences in some somatic lineages for such qualities as berry color, fruit flavor and aroma, leaf shape and morphology, cluster size, shoot growth, vine habit, and yield. One theory posited for the berry color mutation is that pieces of DNA called transposons jump in and out of the anthocyanin (pigment) pathway, changing berry color from the black of the ancestral clone Pinot noir to white and grey and back again. 15 Vezzuli, S., L. Leonardelli, U. Malossini, M. Stefanini, R.Velasco and C. Moser. Pinot blanc and Pinot gris arose as independent somatic mutations of Pinot noir, Journal of Experimental Botany, vol. 63 (18): 6359-6369 (2012). Scientists continue to investigate the mechanism and causation for the clonal variation, which is also significantly influenced by environmental factors. 16 Robinson J. et al.. Wine Grapes, supra at p. 805.

Pinot has proved to be a prolific parent. Pinot and the French grape Gouais blanc have produced at least 21 varieties through spontaneous crosses in northeast France, including Aligoté, Auxerrois, Chardonnay, Gamay noir, and Melon. 17 Bowers J. et al. 1999, supra. The numerous progeny were in part responsible for identity confusion, misidentification, and proliferation of synonym names associated with Pinot noir and varieties that were mistaken for Pinot noir in the early years of development of the California wine industry.

PINOT NOIR

The early history of Pinot noir in California was marked by confusion as to varietal identification, a wild proliferation of synonym names for the Pinot variety, and lack of integrity in the production of wine produced in the name of “Burgundy”. The confusion would not be resolved completely until the 1970’s.

Pinot noir was present in California in the 1880’s under many synonym names. 18 Notebook with handwritten entries, varieties, growers and locality of grapes submitted to the University of California for evaluation in 1888. UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections D-280, box 49: 71. Charles Wetmore in his Ampelography (1884) noted that “the Burgundy Pinot, par excellence of the Burgundy vine”, consisted of a family of varieties, of which Franc Pinot was the chief. Plantings existed in Livermore (Charles Wetmore, J.R. Smith), Cupertino (J.T. Doyle) and Sonoma (J.H. Drummond). H.W. Crabb had several Pinot noir clones in his nursery collection in Napa but they were not successful on a commercial scale at that time. 19 Sullivan C.L., Napa Wine a History. 2d ed. Wine Appreciation Guild, Napa CA. (2008), p. 137.

The Burgundy Pinot varieties were not cultivated in sufficient quantity in 1884 for Wetmore to make a judgment on the merits for the State of California. He opined that the Pinot variety had been abandoned as "not practical" on account of shy bearing. Wetmore reported that those who tried Pinot varieties observed that Pinot de Pernand appeared to be the most fruitful. Wetmore concluded that the Pinot varieties might be successful in coastal counties but ripened too early for the hot valleys. He and others such as Drummond at Dunfillan in Sonoma were also experimenting at the time with “long” (cane) pruning of the variety. 20 Wetmore, C.A. Part V. Ampelography. Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-83 and 1883-84, p. 116 (1884).

The University reported on “Red Burgundy Type” grapes in 1892 and 1896 in a continuing report on red wine grapes suitable for California. The difficulty in evaluating the wines sold as “Burgundy” at that time was exacerbated by confusion caused by inappropriate varieties being included in the wines. Wetmore’s first report to the Board of Viticultural Examiners stated: “What passed for Burgundy in California was really any heavy claret”. 21 Sullivan C.L. Napa Wine a History, supra at p. 137. The name “Burgundy” was applied to grapes completely distinct from each other and not resembling in any way the “Pinots or true Burgundies”, which were known for low acid, high sugar and low color. Grapes such as Chauché noir, Trousseau, Robin noir, Cinsaut and Crabb’s Burgundy (later recognized as Refosco) were grown under the name of “Burgundy” in California vineyards. 22 Hilgard E.W. 1896. Report of Viticultural Work during the Seasons 1887-1893 with data regarding the Vintages of 1894-1895, Part I.a. Red wine grapes (continued from report of 1892), pp. 6-7, California Agr. Exp. Sta. Rept. [hereinafter cited as 17th Report 1896]. The wines produced in the name of “Burgundy” varied from highly acidic and tannic wines to wines to those with low acid and tannin levels. Hilgard attributed the reliance on inappropriate varieties to failure of the characteristic grape of Burgundy,the Pinot, to yield satisfactory crops and wine-making results in California.

Multiple synonym names for Pinot noir also added to identity confusion. The variety was planted in California in the 1880’s and 1890's under the names Pinot noir, Black Pinot, Pinot Noirien, “Pinots”, Pinot St. George, Blauer Burgunder and Franc Pinot. Pinot de Pernand (Pernant) was considered in Burgundy to be “a distinct variety of the Pinot noir” and was selected as a more stable bearer with larger bunches and more berries; Pinot de Pernand was listed separately from the other red Pinots in university evaluations. Blauer Burgunder grapes were reported to be a variety known as Bouguignon noir from the Beaujolais region of France but known to Hilgard to be Pinot noir. The multiple synonym names were all used on grape samples submitted to the University of California for evaluation between 1887 and 1889 from the station vineyards at Cupertino, Mission San Jose and Livermore. 23 Hilgard E.W. and L. Paparelli. 1892. Report of the Viticultural Work during the Seasons 1887-1889, with data regarding the Vintage of 1890, Part I. Red Wine Grapes, pp. 90-100, Being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University, University of California - College of Agriculture [hereinafter cited as 13th Report 1892]. Hilgard was aware that the grapes known by the synonym names were all Pinot noir. Pinot noir was later planted in university experiment station vineyards at Paso Robles (1897) and Jackson, California (1889) as Pinot noiren, "black Pinots", Pinot noiren Franc, Pinot St. George, Pinot de Pernand, Pinot Noirien, Frank Pinot, and Blauer Burgunder. 24 UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 49: 7.

The Pinot de St. George grown in California in those early days was considered to be a Pinot noir clone, with smaller bunches and looser clusters. It was thought the name arose from importation from the St. Georges Vineyard in Burgundy. The variety was known as Pinot St. George until some of the vine material was eventually revealed in 1997 to be the French grape Négrette. 25 Robinson J. et al. Wine Grapes, supra at pp. 712-713. FPS has five Pinot St. George selections that were renamed Négrette in 2003. Negrette 01.1 was created by microshoot tip tissue culture from material received from Paul Truel, le Domaine de Chapitre (now Montpellier Supagro), Pabellan, Montpellier, France, in 1977. (P.I. 422382, FPS S1). Negrette 04 (formerly Pinot St. George 04) originated from the former Foothill Experiment Station in Jackson, California, in 1965 where it was planted as Pinot St. George (Jackson D8 v9). Negrette 05 (formerly Pinot St. George 05) was also from the Foothill station in the "Persian block" location R14. Negrette 06 (formerly Pinot St. George 01) is a heritage selection that came to FPS around 1960 from the Sambuccetti vineyard in California.

Pinot noir was tried at least as early as 1885 at the California Agricultural Experiment Station. Hilgard never recommended Pinot noir as commercially viable for winemaking in California, but only as a luxury in particularly favorable locations. His reasons were the low production levels of Pinot vines and the unstable character and indifferent quality of the wine when produced in a warm climate.He cited specific issues such as difficulty delivering the fragile grapes to the cellar without damage and lack of proper methods and care in fermentation. Hilgard felt that, under the conditions of wine-making in California in the late 19th century, it would be nearly impossible to make and keep a perfectly sound wine of Pinot alone. 26 Hilgard E.W., 17th Report 1896, supra; Hilgard and Paparelli. 13th Report 1892, supra at pp. 89, 105; UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 78: 29; Sullivan C.L. Napa Wine a History, supra at p. 137. He recommended blending with more acid and a more robust variety.

Hilgard’s successor Frederic Bioletti made brief reference to Pinot in his 1907 Experiment Station bulletin. He acknowledged that quality grapes such as Pinot, Chardonnay or Cabernet [Sauvignon] were suitable for the vineyards of the California Coast range but cautioned that light bearing varieties should not be planted in rich Valley soils. Pinot was not included in the list of the top wine grapes in the 1907 University recommendations for coastal counties. 27 Bioletti F.T. The Best Wine Grapes for California – Pruning Young Vines – Pruning the Sultanina, California Agricultural Experiment Station bulletin no. 193, pp. 141-160 (1907); Bioletti F.T., Grape culture in California, California Agricultural Experiment Station Bul. 197: 115-160 (1908). The Pinot varieties were not mentioned in a 1929 circular (rev. 1934) published by the California Agricultural Extension Service, in either the red wine or white wine sections. 28 Bioletti F.T. Elements of Grape Growing in California, California Agricultural Extension Service, Circular 30, March 1929, revised April 1934, pp. 31-37.

In 1910-1911, Bioletti installed several Pinot noir selections in block D (the Variety Collection) of the first vineyard of the Department of Viticulture at the University Farm at Davis. He planted Pinot St. George, Pinot de Pernand, and a variety he labelled Gamai Beaujolais (later revealed to be a Pinot noir clone). The Gamai Beaujolais was sourced from the Richter Nursery in Montepellier, France. Bioletti also included a Meunier and a Pinot blanc, along with Pinot Chardonnay. 29 Davis: Vineyard Maps and Plans, page 10. UC Davis, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 2: 11A; see also, Request from University of California to H. Morise Fils & Cie, Havre, France, to order Gamai noir cuttings from Richter Nursery, 14 November 1911, UC Davis Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 16: 10. Although Bioletti ordered a Pinot noir selection from Richter Nursery in 1911, no grape variety by that name was planted in the block D Variety Collection in that first vineyard at Davis. Bioletti later (1929) renamed the St. George variety for the relocated Variety Collection where the planting was known as “Pinot noir (St. George)”. 30 UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Bioletti D-363, box 2: 10, page 8.

The Pinot Pernand selection survived transfer over the years through several iterations of the Department vineyard on the Davis campus until Pernand eventually came to FPMS in 1966. Pinot Pernand appeared on the list of registered vines at FPMS in 1971 but disappeared from the foundation vineyard and list by 1978. Presumably, DNA analysis would have shown Pinot Pernand to be another clone of Pinot noir.

Amerine and Winkler reinstituted the university evaluations into appropriate wine grape varieties after Prohibition and reported their findings in 1944 and 1963. They noted that results of university testing over the years had been “remarkably similar” to previous efforts and led only to a “lukewarm recommendation of Pinot noir for California”. 31 Amerine M.A. and A.J. Winkler. California Wine Grapes: Composition and Quality of Their Musts and Wines. Bulletin 794, California Agricultural Experiment Station, p. 32. Division of Agricultural Sciences, University of California (1963). They concluded that Pinot noir wines from vineyards in Winkler region I (cooler coastal) had excellent aroma and flavor and were fruity and soft and recommended the variety for table wines in that region. 32 Amerine, M.A., and A.J. Winkler. Composition and quality of must and wines of California grapes. Hilgardia 15(6): 559(1944, rev. 1963). They reported in the same publication that Pinot Pernand closely resembled Pinot noir and Meunier but found that Pinot noir had better color; they found “no reason” to plant Pinot Pernand. 33 Amerine and Winkler, Hilgardia, supra at p. 649.

Early Pinot noir selections from abroad

Pommard clones

Charles Wetmore recognized the “celebrated vineyards at Pommard and Chambertin” in the Côte d’Or, Burgundy, in his 1884 report for the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners.

34 Wetmore, C.A. Part II. Development of viticultural industry in California. Second Annual Report of the Chief Executive Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners for the Years 1882-1884, pp. 59-60 (1884).

Harold Olmo visited the area on his 1951 trip to collect quality French wine grape varieties for the grape variety collection at UC Davis. In a letter to the Wine Institute requesting financial support for his trip, Olmo stated that his mission was to locate superior and disease-free strains of certain wine grape varieties then available in Switzerland, France, Germany and Austria, with particular focus on Pinot noir, Gamay noir, White Riesling, Chardonnay and Red Traminer.

35 Olmo H.P. letter to Dan Turrentine, California Wine Institute. March, 1951. UC Davis Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 49: 41.

Olmo selected four vines on October 11, 1951, from what he identified as the “Les Croix Vineyard, Pommard, France”. 36 Olmo H.P. Clones of Pinot noir, p. 6. UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, boxes 66: 67, 76: 30. The Pommard clone is one of the few selections in the FPS Pinot noir collection that originated from cuttings taken directly from a producing European vineyard, as opposed to a plant collection maintained by government-operated experiment stations or suitcase imports via California vineyards. 37 Haeger J.W. North American Pinot noir, supra at p. 139.

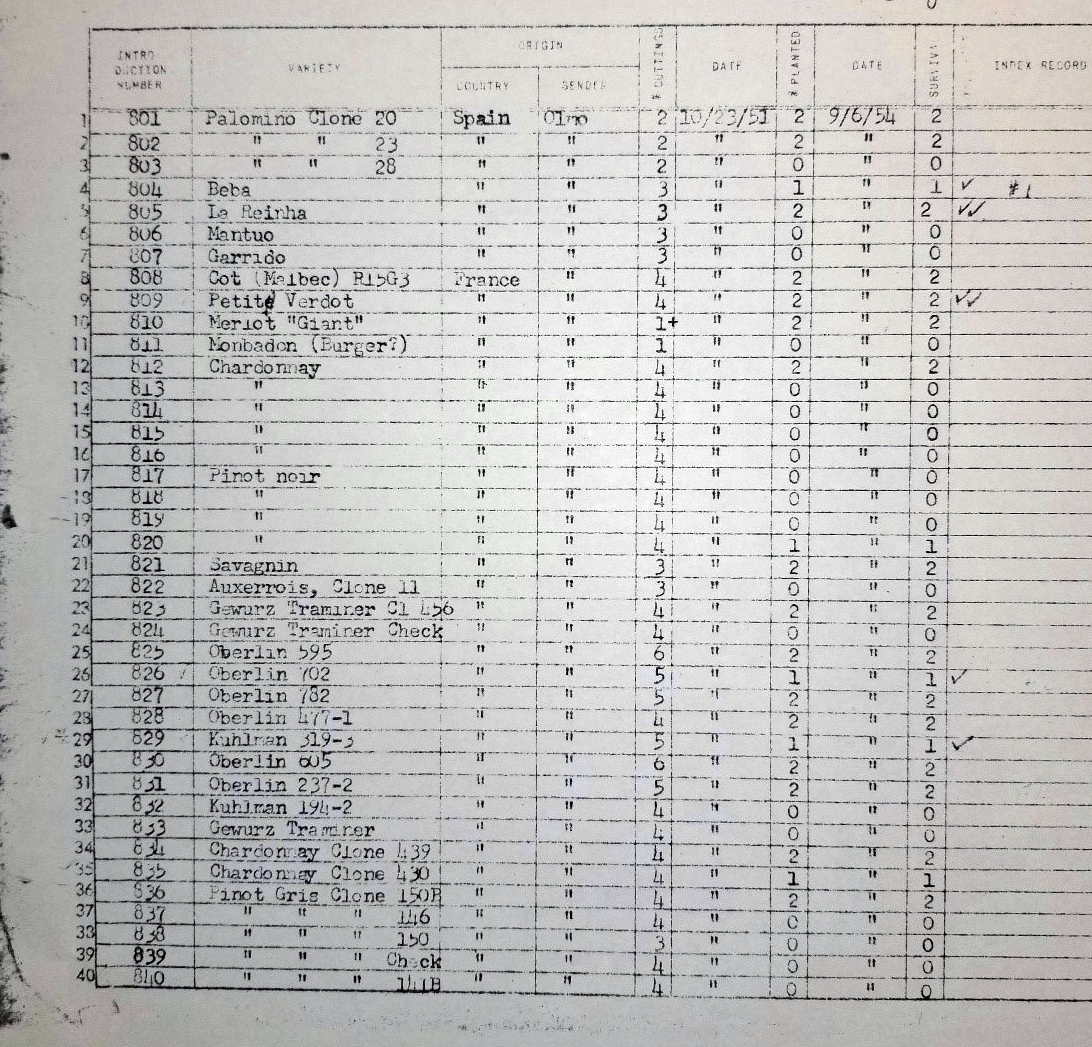

A binder containing a record of the grape introductions managed by William Hewitt at Davis (see Chapter 4: Foundation Plant Materials Service, 1956-1990) shows that four selections named Pinot noir arrived at Davis on October 23, 1951. The record reflects that Olmo caused the cuttings to be sent to Davis from France. Four separate groups of four cuttings per group appear in the binder. Olmo assigned a separate collection number for each set of four cuttings. The four Pinot noir selections were given “Introduction numbers” 817 through 820. The only one of the four selections that survived the shipping and testing process was Pinot noir number 820. After completion of index testing in 1954, that selection appeared on the 1956 list of registered grapevines at FPMS as Pinot noir-1 (location O.F. 9 v 9-11). Its origin was described as ‘820 Pommard, France’.

The selection was moved to the new FPMS Hopkins Foundation Vineyard in 1961 and planted in row D4 vines 1a, 2a, 3a, 4a-8. The selection number for the D4 vines was changed to Pinot noir 04A and later to 04. Two iterations of material collected from the vine at D4 v1a underwent heat treatment therapy and became Pinot noir 05 and 06 in 1965. Pinot noir 05 and 06 were together released by FPMS in the late 1960’s as the heat treated “superclone Pinot noir 103”. Pinot noir 04 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy and the resulting vine was released as Pinot noir 91 in 2002.

Pinot noir 04, 05 and 06 have been known as the "Pommard clone" by the industry. The Pommard selections were widely distributed throughout California from the 1950’s through the 1970’s. They were used in coastal vineyards in California for table wine production. The Pommard clone accounted for 2/3 of the Oregon Pinot noir plantings prior to the arrival of the Dijon clones in the 1980’s. The Pommard clone has been valued in winemaking for its good color, intense fruit and spiciness.

“Beba” from Spain

Another Pinot noir clone from that 1951 shipment of grape clones from Europe remains in the FPS grape collection with ambiguity surrounding its origin. The Hewitt import binder and FPS database give the origin of the “Beba” variety in the shipment as “Spain”. Spain has never been noted for its Pinot noir production. Olmo wrote in his journal for the 1951 trip that he did collect cuttings in Spain for a variety known as “Beba”, a white Spanish grapevine variety used to make sherry. Olmo’s journal indicated that he collected the “Beba” cuttings a few miles outside of Seville. The name “Beba” became assigned to Introduction number 804 in the Hewitt import binder at FPS.

Pinot noir and Beba are clearly unrelated varieties. The facts suggest a label mixup at some time when the vines were sent from Europe. The plant material with Introduction number 804 was named Beba upon arrival at FPMS and was planted in the foundation vineyard in 1961 under that name. The selection remained on the list of registered vines with the name Beba until 1966, when the name was changed to Pinot noir 07A. The selection was renamed again in 1967 to Pinot noir 10. The variety identification as Pinot noir was made at that time by experts at FPMS using visual identification techniques.

Pinot noir 11 and 12 were created from Pinot noir 10 using thermotherapy. All three selections were registered in the California R & C Program from 1967 until 1980, when they were removed from the registered list because they tested positive for the Rupestris stem pitting virus.

In 1999, Pinot noir 10 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy to create Pinot noir 107. DNA evaluation at FPS in 2006 confirmed the identity of the selection as Pinot noir. The source of Pinot noir 10/107 remains unknown.

Wädenswil, Switzerland

Wädenswil is a town in the German-speaking section of Switzerland. Located on Lake Zurich, Wädenswil has been the home of a government-operated research station for fruit growing and viticulture since 1890.

38 Robinson J. The Oxford Companion to Wine, p. 760. Oxford University Press, 3rd ed. (2006).

Olmo travelled to the research station in the fall of 1951 and met with Professor E. Peyer. Olmo examined some Blauer Burgunder vines and requested that Peyer send the selections to Davis.

39 H.P. Olmo letter to John Meyer, Salem OR, March 27, 1985, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 78: 29.

Blauer Burgunder is the synonym name used for Pinot noir in Switzerland.

Six individual Blau (Blauer) Burgunder introductions arrived at Davis in March, 1952, from the Versuchsanstalt für Obst, Wein and Gartenbau in Wädenswil. Five Swiss clones were assigned Plant Introduction numbers that appeared in the Hewitt import binder as follows:

Blau Burgunder Clone Bh V 2/59. PI 199733 (Hewitt import 5308).

Clone St. II . PI 199734 (Hewitt import 5311).

Clone K 10/8. PI 199735 (Hewitt import 5309).

Clone Bl 10/16. PI 199736 (Hewitt import 5306).

Clone PI a/4. PI 199737 (Hewitt import 5310).

A sixth clone appears in the Hewitt import binder with number 5307 but was not assigned a PI number. That clone was Blau Burgunder BIII.

Two of the Blau/Blauer Burgunder clones became Pinot noir 01A (Blau Burgunder BIII, 5307)and Pinot noir 02A and 03A (Blau Burgunder Bl 10/16, PI 199736, 5306). FPS 02A and 03A were propagated from the same source vine. The three selections became known as the “Wädenswil” clones. All three selections appeared on the 1962 list of registered vines. Pinot noir 03A was dropped from registration in 1981 due to positive results for leafroll virus. A heat-treated selection of Pinot noir 02A, designated Pinot noir 30, was never registered in the California R & C Program. Pinot noir 01A and 02A remain in the California program as registered selections and have qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard.

John Haeger surmises that the FPS Wädenswil clones are probably related to a well-known Swiss clone 2/45, which has moderate vigor, moderate to high yields, compact cylindrical clusters, good color and fair tolerance for a variety of mesoclimates. Pinot noir 02A became an important selection, accounting for about 1/3 of Pinot plantings in Oregon and a substantial amount of California plantings. Haeger explains that 02A is valued in Oregon and northern California as a blending component for its “brilliant, high-toned berry fruit and impressive perfume”. 40 Haeger J.W. North American Pinot noir, supra at p. 140.

Clevner-Mariafeld, Switzerland

Wädenswil was also the source of two additional Pinot noir selections at FPS. Hewitt imported six sets of cuttings in 1965-66 that were labelled “Clevner-Mariafeld” Wädenswil clones A-1, B-1, C-1, D-1, E-1 and F-1 (USDA Plant Identification number 312435). Two of the selections were ultimately released in 1974 as Pinot noir 17 (C-1) and Pinot noir 23 (D-1). The two clones are referred to as the “Mariafeld” or “Clevner Mariafeld” clones.

“Clevner” or “Klevner” is a euphemism for several grape varieties cultivated in German-speaking regions. The name is also reportedly derived from the Swiss version of the name of the town of Chiavenna in northern Italy. The town is situated at the north end of Lake Como. The varieties were supposedly taken from the Chiavenna area across the Alps to Switzerland in the 1500’s. “Mariafeld” was the name of the estate of Swiss Army Commander-in-Chief General Ulrich Wille, who maintained vines on his estate on Lake Zurich. 41 Haeger J.W. North American Pinot noir, supra at p. 141. Haeger reports that the Mariafeld clones are known for their “blueberry-like color in the vineyard”, open cluster architecture and resistance to bunch rot.

Side by side comparison of the cluster of Pinot noir 23 with more traditional Pinot noir clones illustrates that Mariafeld berries and clusters can be much larger (~250 grams) than traditional berries and clusters, such as those produced by French clones 115 and 777 (~125 grams). The Mariafeld clone has been among the higher-yielding clones in trials in California, Germany and Switzerland. However, Pinot noir 23 has been intermediate yielding in New York State and low yielding in a trial in the Willamette Valley in Oregon. 42 Castagnoli, S.P. and M.C. Vasconcelos, “Field Performance of 20 Pinot noir Clones in the Willamette Valley of Oregon”, HortTechnology, January-March 2006, vol. 16(1), pp. 153-156.

Pinot noir 17 was removed from the FPS program in 1980 positive test results for Rupestris stem pitting virus; a new selection was created from selection 17 using tissue culture therapy and became Pinot noir 109 in 2004.

Pinot noir 23 has a more complicated history at FPS. The Swiss selection has been very popular with some grape growers and winemakers for a combination of high quality and good yield. In May 2006, FPS sent a notice to customers to whom it supplied Pinot noir 23 plant material, informing them that Pinot noir 23 was infected with a newly-discovered grapevine virus, leafroll 7 (GLRaV-7). Testing of foundation vines with PCR technology led to the conclusion that the selection had always been infected with GLRaV-7, which appeared to be mild or non-symptomatic on prior Cabernet franc field index tests. A new selection for this Mariafeld clone was produced by microshoot tip tissue culture therapy in 2007 and was given the name Pinot noir 123. 43 Virus Status of Pinot noir FPS 23, FPS Grape Program Newsletter, November 2006, p. 3.

Early selections from California vineyards

Inglenook/Martini clones

Harold Olmo initiated his clonal trial program on wine grape varieties from California vineyards beginning in 1937. In the 1940’s and early 1950’s, Inglenook Winery in Napa won gold medals for its Pinot noir wines.

44 Sullivan C.L. Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to the Present, 2d ed. p. 256. Napa Valley Wine Library Association (2008).

The Inglenook vineyard had been planted in the 1930’s. When Olmo went in search of Pinot noir clones in 1951, he and Louis M. Martini turned to the Inglenook vineyards at the Niebaum estate on Highway 29 in Rutherford. “Pinot noir clones 41 through 60” were collected in August, 1951, from a vineyard west of the hill near the residence.

45 Handwritten documents entitled “Bud selection” and “Clonal selection”, August 1951, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 77: 10.

The vineyard manager recalled that the buds were selected and collected from “very different looking vines” in the block from which Olmo and Martini selected the Pinot noir clones.

The Inglenook Pinot noir clones underwent testing at the Martini Stanly Lane vineyard in the Carneros region of Napa. Olmo selected two of those clones for the California R&C Program – Martini 58 and Martini 45. An article in the FPS 2003 Grape Program Newsletter mistakenly reported that Olmo selected material from two vines of the same clone, Martini 58, and concluded that both selections were Martini 58. 46 History of Pinot noir at FPS. FPS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2003, p. 11. However, there is convincing evidence from sources at FPS that two different clones from the Stanly Lane trial were send by Olmo to FPS – Martini clone 58 and clone 45.

Each row in the Martini vineyard at Stanly Lane was planted with a different Inglenook Pinot noir clone. The binder maintained by Goheen and his staff for index testing of material destined for the FPMS foundation vineyard showed the clones sent to FPMS sometime prior to 1966 as originating from two different rows at the Stanly Lane vineyard. The two Stanly Lane vine locations mentioned in the Goheen binder were Martini 7 v13 (eventually FPS 13) and Martini 17 v18 (eventually FPS 15). The FPS database reflects the same two source locations as the Goheen binder. Olmo maintained material from both sources for observation and trials in Department vineyards on the UC Davis campus; his own records relative to those two clones show material from two different rows, "Martini 7: 13" and "Martini 17: 18". 47 See also, Olmo, Clones of Pinot noir, supra; Pinot noir clones, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 49: 40 and box 28 (map of Louis Martini Stanley Vineyard).

The clone from Stanly Lane row 7 vine 13 was Martini 58, also known as "California selection 58”. The selection underwent heat treatment at FPMS for 105 days and was eventually released as Pinot noir 13. Pinot noir 13 was also known as “superclone 104” when marketed to the industry in the early 1970's as one of the new heat-treated clones from FPMS. 48 Olmo, Clones of Pinot noir, supra; Alley C.J. Current Status on Clonal Research and New Wine Varieties, 3rd Annual Wine Industry Technical Seminar Proceedings, U.C. Davis, November 13, 1976, republished in Wines and Vines magazine, April 1976. Pinot noir 13 was included in the Carneros Creek clonal trial managed by Francis Mahoney and Curtis Alley beginning in 1974. FPS 13 (clone L in the Carneros trial) scored consistently well in the top group in wine tastings both at UC Davis and Carneros Creek Winery and reportedly produced "moderate yields". 49 Nelson-Kluk S. Carneros Creek Clonal Trial. FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2002, page 10. There are no “Pinot noir 13” foundation vines at FPS in 2017. The vines were removed because they suffered from disease. The material has been preserved in pots in the FPS greenhouse.

Alley and Mahoney wanted to compare heat-treated and non-heat-treated versions of Martini 58. A non-heat-treated version of Martini 58 was included in the clonal trial at Carneros Creek Winery as clone V (see below for the discussion of the Carneros Creek Winery trial). The heat-treated version of the clone (Pinot noir FPS 13, clone L) performed better than the non-heat-treated version (clone V). According to Mahoney, the non-heat-treated clone V produced a nice wine with clean tones but no complex undertones. The wine had cherry and fresh strawberry flavors. The clone made a moderate, middle-balanced wine. Production levels were moderate. 50 Nelson-Kluk, Carneros Creek Clonal Trial, 2002, supra at p. 11. Clone V was ultimately submitted to FPMS for the foundation vineyard. After completion of testing, the selection was released in 1999 as Pinot noir 66, vines of which remain in the FPS Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2017.

Pinot noir 15 was collected from row 17 at the Martini Stanly Lane vineyard. A clone named "Martini 45" was planted in row 17. Olmo chose vine material from row 17 vine 18 for FPMS and presented it for testing sometime prior to 1966. The material underwent heat treatment therapy for 69 days. It was released in 1974 as Pinot noir 15, which was not as successful as Pinot noir 13. 51 Olmo, Clones of Pinot noir, supra at p. 7. Sales records at FPS show that the amount of Pinot noir 13 distributed to customers far exceeded that of Pinot noir 15.

A fourth Pinot noir selection in the FPS foundation vineyard originated from the Inglenook/Martini Stanly Lane clones and was evaluated in the Carneros Creek Winery clonal trial. Martini 54 was clone M in the Carneros trial. Mahoney reported that "M had bright fresh Pinot noir flavors, moderate middle texture and a very clean finish. It was good but its best characteristics were its balance and varietal character in a blend. It made a strong cherry and fresh strawberry statement. It didn't give that sort of deep textural follow through". 52 Nelson-Kluk, Carneros Creek Clonal Trial, 2002, supra at p. 11. Martini 54 came to FPMS in 1996 and underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy immediately to qualify for the foundation vineyard at a time when RSP-positive material was ineligible. The selection was released in 2000 as Pinot noir 75.

Foothill Experiment Station, Jackson, CA

In the early 1960's, USDA plant pathologist Austin Goheen collected multiple Pinot noir selections from the former UC Foothill Experiment Station near Jackson in Amador County, CA (see chapter 1 for a discussion of the seven UC experimental vineyards from the 19th century). The University had abandoned the station decades earlier and it became overgrown. Goheen rediscovered the Jackson vineyard in 1963 and located old maps and records for the station in Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley.

The maps of the Foothill Station showed vines with the names: Pinot St. George (B5 and L1-3), Pinot de Pernand (B6 and L4) Frank Pinot (B8), Pinot Noiren (B7 and L5), Meunier (B9), Meunier (L7), Blauer Burgunder (B10 and L8), and Robin noir (L9). Block B was labelled "Burgundy"; the vines in that section were planted in 1889 from the UC Experiment Station in Cupertino (B7, B8, B10) and from the Central Experiment Station at Berkeley (B5, B6, B9). Block L (rows 1-9) was planted in 1889 with vines that originated from the vineyard at the Berkeley Station.

Pinot noir 01, 29 and 106

Goheen collected cuttings from a vine labelled "Pinot St. George" at location L1v1 at the Foothill Station. He performed index testing on the material at FPMS beginning in 1965 under the name Pinot St. George. The material was also known as Pinot franc 01 in the Goheen indexing binder. The selection passed the disease tests necessary at the time to qualify it for the California R&C Program without any treatment and was planted in the foundation vineyard in 1966 as Pinot noir 01 (FV E6 v1-2). The selection was not registered because of concerns about varietal identification. The vines were eventually removed in 1999.

Meanwhile, Goheen had collected a second set of cuttings from another Pinot St. George vine at location L3v5 in the Foothill Station vineyard. Those cuttings were submitted for index testing at FPMS beginning in 1966, again under the name Pinot St. George (also known as Pinot franc). The tests were completed and the selection was planted in the FPS foundation vineyard in 1967 (location FV H11 v 11-12) without registration due to concerns about identification. The selection was eventually given the selection name Pinot noir 29. Both Pinot noir 01 and Pinot noir 29 originated in 1889 from the vineyard at the Central Experiment Station at Berkeley.

Despite the concern about varietal identification, Oregon researchers included Pinot noir 29 in several of their Pinot noir trials and rated it in the highest wine quality group. The researchers acknowledged the prior questions about authenticity but concluded that findings on anthocyanin pigments discovered during the trial clearly demonstrated that FPS 29 was Pinot noir.

53 Price, S.F. and B.T. Watson. Preliminary Results from an Oregon Pinot noir Clonal Trial. International Symposium on Clonal Selection, American Society for Enology & Viticulture, pp. 40-44 (1995).

Watson, Lombard, Price, McDaniel and Heatherbell. Evaluation of Pinot noir clones in Oregon. Proceedings Second International Cool Climate Viticulture & Oenology Symposium, Auckland, New Zealand, pp. 275-278 (January 1988).

The findings from the Oregon researchers generated interest in Pinot noir 29, and several wineries ordered the selection from FPS between 1988 and 1999 even though both source vines were unregistered. Disease tests were repeated at FPMS in the late 1990's to attempt to qualify Pinot noir 29 for the California R&C Program. The selection tested positive for leafroll virus in 2002 and again in 2005.

Pinot noir 29 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPMS in 1998. The treated material successfully completed testing and was advanced to registered status in the California R&C Program in 2003 as Pinot noir 106. DNA analysis performed at FPS in 2006 confirmed the identity of the selection as Pinot noir.

Pinot noir 09

Pinot Noirien from the UC Experiment Station at Cupertino, California, was planted at location B7 of the Foothill Experiment Station in 1889. Goheen took cuttings from that vine in 1963 and brought them to FPMS as "Jackson selection #2 (B7)". The original material successfully completed testing and was released as Pinot noir 09 in 1974.

Pinot noir 16

Pinot noir 16 also originated from block B at the Foothill Station, but the source vine is not clear. Several vines in block B had synonym names for Pinot noir - Pinot St. George, Pinot de Pernand, Pinot Noirien, Frank Pinot and Blauer Burgunder. Goheen labeled the material he harvested in 1966 as "Jackson B Block Cl. 1".

The Gamay Beaujolais clone of Pinot noir

Beaujolais is a viticulture region near Burgundy in France known for producing a distinctive type of wine. “Gamay noir a jus blanc” (also known as “Gamay”) is the predominant variety used in the production of Beaujolais wine. In the early years of the California wine industry, viticulturists and winemakers imported multiple varieties for what they believed to be the grape that had been used to make the "Gamay wines of the Beaujolais district" in France.After Prohibition, vines named “Gamay Beaujolais” were distributed to many growers from the university grape collection at Davis for use in making Gamay Beaujolais wine. At the time, it was mistakenly thought that the “Gamay Beaujolais” selection at the university was the same Gamay grape grown in Beaujolais, France. The names "Gamay" and "Gamay Beaujolais" became associated in the United States with a particular light red style of wine.

When Olmo started at the university in the early 1930's, one of the varieties in the university grape collection was called "Gamay Beaujolais". Published wine reports after 1930 referred to that university plant material as “Gamay Beaujolais”, which was distributed to industry members as such. Olmo saw that the variety did not conform to what he knew to be the Gamay grown in the Beaujolais viticultural region of France. 54 Olmo H.P. Gamay Beaujolais. Undated.UC Davis, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 56: 1. Amerine and Winkler reported in 1963 that cluster and leaf morphology and wine aroma showed that the grape grown as Gamay Beaujolais in the university vineyards was “probably a member of the Pinot family”. They also observed that studies showed a deficiency in color for these grapes. 55 Amerine and Winkler, 1963, supra, at p. 20.

In 1970, Olmo and the Department of Viticulture reported to the California grape and wine industry that the university vines known as Gamay Beaujolais were in fact a clone of Pinot noir. Olmo advised that the "true Gamay" was a different variety growing in California which he named "Napa Gamay". Confusion was compounded in the 1970’s by the importation from France to California of a third variety called Gamay noir. None of the three varieties at issue would ultimately keep the name Gamay Beaujolais.

Industry members became extremely concerned when the misidentification of the university Gamay Beaujolais vines was revealed, because those vines formed the basis of plantings in California used to produce a popular wine named Gamay Beaujolais. 56 Olmo H.P. correspondence to California grape and wine industry members, UC Davis, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 56: 1. The U.S. Department of Treasury decided on a temporary basis to allow wines produced from the university Gamay Beaujolais, Napa Gamay and Pinot noir grapes to be labelled as “Gamay Beaujolais” wine, pending a final resolution of the erroneous naming of the grape varieties in the United States. Olmo believed that the growers would eventually make the correction to the name of the university clone on their own, since Pinot noir was considered a more valuable variety for wine production than was Gamay Beaujolais. 57 Harold P. Olmo, “Plant Genetics and New Grape Varieties”, an oral history conducted in 1973 by Ruth Teiser, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley, 1976, p. 24.

In the 1980’s, a new agency known as the BATF (Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, now known as the TTB) began the process of evaluating variety names to formulate an authoritative list for grape varieties used to produce American wines. In 1982, they established the Winegrape Varietal Names Advisory Committee to evaluate grape names and synonyms for use in the United States. 58 47 CFR 13623, March 31, 1982.

In 1993, Dr. Carole Meredith of the UC Davis Department of Viticulture & Enology reported results of a DNA evaluation confirming that the following grapes shared a DNA profile: the clone widely used in California for Gamay Beaujolais wine; the university selections Gamay Beaujolais FPS 18 through 22; and Pinot noir FPS 01. The university Gamay Beaujolais selections were proved to be Pinot noir and not a Gamay. 59 Meredith C.P. et al. DNA Fingerprinting Characterization of some Wine Grape Cultivars. Am.J.Enol.Vit. 44 (3): 266-274 (1993); see also, Wolpert J.M. Vineyard and Winery Management, July/August 1995, pp. 18-21.

BATF formally addressed the Gamay Beaujolais issue in 1997. They decided to phase out use of the name “Gamay Beaujolais” on wine labels in the United States. BATF noted that since the grape known as Napa Gamay and the UCD Gamay Beaujolais (Pinot noir) were two distinct varieties, wine made from a blend of both grapes should not be labeled with a single varietal designation. BATF ruled that, in order to use the name Gamay Beaujolais on a wine label, the wine must contain at least 75% “Napa Gamay” (or Valdiguié, see below) and/or Pinot noir grapes. The 75% rule was phased out by 2007, at which time the term “Gamay Beaujolais” was no longer allowed as a designation for American wines. 60 Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, 92F-042P, TD ATF-388, 27 CFR Part 4, vol. 62, no. 66, April 7, 1997.

The FPS foundation collection has at one time or another contained grapevines with the names of all the varieties associated with the Gamay Beaujolais identification issue – Gamay Beaujolais, Napa Gamay, Gamay noir, Pinot noir. The grape variety names were eventually sorted through, and many FPS selections were renamed to clarify any possible misunderstandings. Selections involving three distinct varieties were renamed accordingly. No selection in the FPS foundation vineyard in 2017 is named Gamay Beaujolais.

Napa Gamay to Valdiguié

When the confusion over Gamay Beaujolais surfaced in the 1970’s, Olmo informed the grape and wine industry that the "true Gamay Beaujolais" from the Beaujolais district in France was growing in vineyards in Napa; he referred to that variety as "Napa Gamay" at the time to distinguish it from the then-university Gamay Beaujolais clone.

61 Olmo. Gamay Beaujolais.Undated. supra.

The Napa Gamay grape had gained popularity in California during Prohibition because of its high productivity. French ampelographer Pierre Galet visited Napa in 1980 and identified the "Napa Gamay" variety (also known as Gamay) as the French grape Valdiguié. The identification has since been validated using DNA technology. Valdiguié fruit was allowed in wines labelled "Gamay Beaujolais" until 2007.

62 Christensen, L.P. Valdiguié. Wine Grape Varieties in California, supra at pp. 155-157.

In the 1960’s and early 1970’s, FPMS had three selections in the foundation vineyard that were known as Gamay. The three (Gamay 01, 02, and 03) were all from the same source - a heritage clone that originated from Larkmead Vineyards in Napa. Gamay 02 and 03 were heat-treated versions of the Larkmead clone and were included as #116 in Curtis Alley's “superclones” in the late 1960's. The three selections underwent several name changes, first to Napa Gamay and then to Valdiguié (2003) while in the FPS grape collection. The Larkmead heritage selections are now known as Valdiguié 02, 03 and 04 at FPS.

A second Valdiguié heritage clone was donated in 2002 to the FPS public grapevine collection by Gary Morisoli from the Morisoli Heritage Vineyard in Napa. As of 2017, the selection was undergoing testing and treatment at FPS.

Gamay Beaujolais to Gamay noir

Gamay noir is an important variety in the Burgundy-Beaujolais region and the Loire Valley in France and was first imported into California in 1973.

63 Bowers J. et al. Science 1999, supra.

Two selections were imported to FPMS in 1993 as the "true Gamay Beaujolais from France" and were originally given the name Gamay Beaujolais in the foundation collection. Gamay Beaujolais 01 was reported to be French clone #509, imported for Beringer Vineyards. That selection (Gamay Beaujolais 01) was not the same grape material or selection as the Gamay beaujolais-1 described below in Block A from 1956. The Beringer selection was renamed Gamay noir 04 in 1996 after identification by French ampelographer Jean-Michel Boursiquot. FPS now has many generic French clones of Gamay noir in the foundation collection, as well as the official French clone Gamay noir ENTAV-INRA® 358.

“Pinot noir, GB type” at FPS

The Pinot noir selections of the “Gamay Beaujolais type” at FPS all originated from a single vine in an old UCD Viticulture Department vineyard on the Davis campus. Four separate cuttings of "Gamay Beaujolais" were collected from a vine in the UCD Armstrong vineyard and submitted to FPMS for testing in 1955. All four selections were taken from the same source vine in the Department variety collection - vine I (eye) 60: 15. That vine material can be traced with reasonable certainty to the first vineyard designed and planted by Bioletti at the University Farm in Davis in 1910-1911.

A vineyard map prepared by Frederic Bioletti in 1910-1911 for the new vineyard at the University Farm shows the Vitis vinifera collection of the Department of Viticulture planted in "Plot D". A vine labelled "Gamai beaujolais" from Richter Nursery in Montpellier, France was planted in Plot D, row 10, vines 13-16. Other Pinot varieties were planted in row 10 as vines 1-4 (Pinot St. George), vines 5-8 (Pinot de Pernand) and 9-12 (Meunier). Block D row 4 vines 5-8 were Chenin blanc from Richter Nursery, with the name “Pinot blanc” in parentheses after name of the nursery. 64 Davis: Vineyard Maps and Plans, page 10. UC Davis, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 2: 11A; see also, Request from University of California to H. Morise Fils & Cie, Havre, France, to order Gamai noir cuttings from Richter Nursery, 14 November 1911, UC Davis Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 16: 10.

The Department variety collection was moved over the years to other locations at the University Farm as the viticulture discipline developed on the Davis campus. The variety collection was maintained throughout the Prohibition era. In 1929, a vineyard map of the Vitis vinifera varieties at Davis shows "Gamai beaujolais" at vineyard block VIII B2 v 11-12, which was eventually renumbered by Olmo as vineyard block D2 v 11-12. Olmo's vineyard maps and wine grape evaluation records indicate that material from D2 v11-12 was propagated to locations C81: 1-22, then to C2: 9-10, and finally to I (eye) 60: 15. 65 Olmo H.P. Alphabetical list of varieties and locations, Armstrong Vineyard, August 1950. Foundation Plant Services, Department Records; Vitis Vinifera Varieties, Davis Nov. 1929, Frederic Bioletti, D-363, box 2:10, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

The four cuttings taken from the vine at row I(eye) 60: 15 in the UCD Viticulture variety collection underwent testing at FPMS, after which they were planted in the Armstrong foundation vineyard as “Gamay beaujolais-1”. The list of registered vines from 1956 shows Gamay beaujolais-1 in Block A row 12 v 29-32. That material was released to the public in the winter of 1958-59.

Five “Gamay Beaujolais” selections were installed in the new FPMS foundation vineyard on Hopkins Road in the 1960’s. For one of the five new selections, Goheen returned to the original source vine (Department of Viticulture vineyard, I60 v15) for cuttings, which he then subjected to heat treatment therapy at FPMS for 141 days. That selection ultimately became known as Pinot noir (GB) 22. Alley also distributed Pinot noir (GB) 22 as “superclone Pinot noir 105” in 1971 when FPMS was marketing the new heat-treated clonal material to the industry. Pinot noir 22 is the only Gamay Beaujolais selection that Goheen submitted to heat treatment therapy.

The four additional “Gamay Beaujolais” selections for the new FPMS Hopkins vineyard were cuttings taken from the registered Gamay Beaujolais vines in the Armstrong vineyard at Block A row 12 vines 29-32. One selection was taken from each vine. Those four selections were sister propagations that were individually tested for virus. After completion of testing, the new selections were planted in the foundation vineyard in 1961 as Gamay Beaujolais 01, 02, 03 and 04. 66 Registered Vines, University of California, Foundation Vineyard, March 13, 1968. State of California, Department of Agriculture, Nursery Services. They were later renumbered Gamay Beaujolais 18 (r12 v32), 19 (r12 v31), 20 (r12 v30), and 21 (r12 v29).

The four sister propagations as well as the heat treated selection (FPS 22) were sold to the industry as “Gamay Beaujolais” until the time that Olmo issued his statement on misidentification of Gamay Beaujolais in 1970. The selections were then renamed “Pinot noir (GB)”. The reference to "GB" or "GB style" is usually included when any of those selections is mentioned to reflect that the material is a distinct Gamay Beaujolais subclone of Pinot noir.

Pinot noir 20 and 21 were dropped from the California R&C Program because they tested positive for leafroll virus. A selection created from Pinot noir 21 using microshoot tip tissue culture therapy was released as Pinot noir 104 in 2003.

Maynard Amerine reported on UC recommended varieties “not then widely planted in California” in a 1955 Wines & Vines magazine article prior to the time the university Gamay Beaujolais selections were renamed Pinot noir. One of those “not widely planted” varieties was "Gamay Beaujolais". Amerine distinguished Gamay Beaujolais from the variety "simply called Gamay" which was then widely grown in the Napa Valley. He concluded that the Napa Valley Gamay was a separate variety because it had much larger clusters and berries and produced less flavorful wines than the Gamay Beaujolais variety.

The university reported on wines made from the Gamay varieties (which Amerine concluded were primarily Gamay Beaujolais grapes) in Amerine and Winkler’s 1944 Hilgardia article. As grown in the university vineyards, the Gamay Beaujolais vines exhibited a distinct "Pinot character" both in fruit and leaf characteristics and wine aroma. The variety ripened early, was not highly productive (2-4 tons per acre) and was of moderate acidity and pH. The wines made from Gamay Beaujolais were not highly colored and some were marked as rosés. The best were fruity and well-balanced. Some of the prewar wines continued to age for 12 to 15 years. In the 1955 Wines & Vines article, Amerine reaffirmed the 1944 recommendation: Gamay Beaujolais grapes were "well adapted to regions I and II" where the variety produced a light, delicate, refreshing wine that was "much above average quality". 67 Amerine M.A., Some Recommended Grape Varieties Not Widely Planted, reprinted from Wines & Vines magazine, 36 (11): 59-62 (1955).

The university Pinot noir GB selections were included in trials of Pinot noir clones. Pinot noir FPS 18 was among the seven clones preferred in the Carneros Creek Winery trials (see below). Pinot noir 22 was included in trials in Oregon, where it was associated with the Pinot droit (France)or "upright" grouping of the four types of Pinot noir clones (see discussion below). The Gamay Beaujolais clone was included in the droit group because it demonstrated an erect plant habit. 68 Price, S.F. and B.T. Watson. Preliminary Results from an Oregon Pinot noir Clonal Trial, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, American Society for Enology and Viticulture. Portland, Oregon (1995), pp. 40-44.

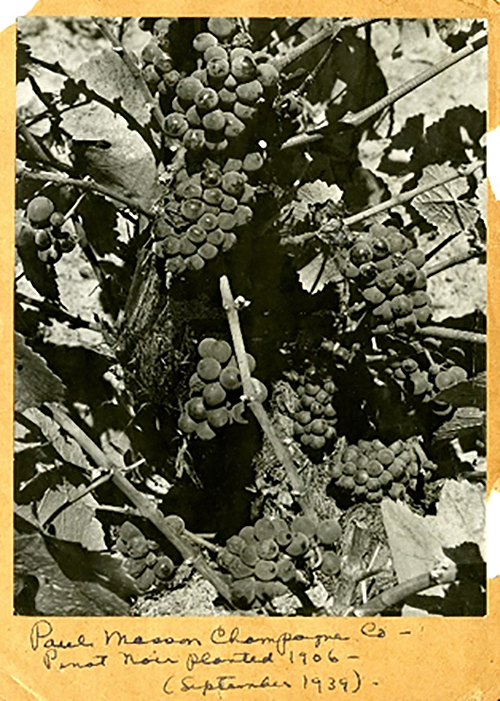

Mt. Eden clone

Several Pinot noir selections in the FPS grapevine collection have a connection to Paul Masson's former La Cresta Vineyard in the foothills near Saratoga, California. Pinot noir FPS 108 (Hanzel Vineyards) was collected directly from the old La Cresta Vineyard (see below, Carneros Creek Winery trial). Martin Ray took cuttings from La Cresta for his new vineyard on a hilltop adjacent to Masson’s vineyard; that new vineyard eventually became Mount Eden Vineyards. Both the Swan clone (Pinot noir FPS 97) and the Mt. Eden Pinot noir clone were reportedly sourced directly from Martin Ray's vineyard.Paul Masson was born in 1859 to a family of winemakers in the Beaune region of the Côte d’Or in Burgundy. He immigrated to California in the 1870's, where he developed a friendship with fellow countryman Charles Lefranc, a pioneer in the commercial wine industry in the Santa Clara Valley in northern California. Masson worked in the Lefranc vineyards. Noting a shortage of champagne wine in the state, Masson decided to establish quality French grape varieties in a California vineyard and make sparkling wine. He travelled to France multiple times in the 1880's and 1890's and obtained Pinot noir and Gamay Beaujolais cuttings from Burgundy on one or more of those trips. 69 Ray, E. Vineyards in the Sky, Heritage West Books (1993) pp. 92, 208-210.

Masson made his highly-acclaimed champagne in California in the French tradition with predominantly Pinot grapes, the best of which he called “Petit Pinot”. 70 Sullivan, C.L. Like Modern Edens: Winegrowing in the Santa Clara Valley and Santa Cruz Mountains, 1798-1981, California History Center, Cupertino California (1982), pp. 24, 89-91; Balzer, R.L. This Uncommon Heritage, The Paul Masson Story. The Ward Ritchie Press, Los Angeles, (1970), p. 26. The Paul Masson collection in the Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, at UC Davis contains a ledger book in French dated 1890-93; that ledger describes the results of winemaking for Cuveé 1892 (including notes about “Le Black Burgundy ou Pinot”) and Champagne 1893 (No.1 Petit Pinot). 71 Masson Ledger, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Paul Masson collection D-357, box 1: 9.

Masson obtained Pinot noir cuttings from Burgundy in 1895 and planted them in his new vineyard La Cresta in the Saratoga Hills, California, in 1896. 72 Haeger, North American Pinot noir, supra, at pp. 143-144; Sullivan, C. Chaine d'Or: the Winemakers of the Santa Clara Valley, in the book LATE HARVEST by Michael Holland, p. 24. A 1901 letter by Masson in the Masson papers in Special Collections at UC Davis referred to "a five-year-old vineyard that contained at that time several varieties including Pinot grafted onto St. George rootstock”. 73 Masson, P. letter to W.O. Chisolin, Esq. dated July 23, 1901, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Masson collection, D-357, box 1: 9. Masson launched the winery "La Cresta" in 1905. 74 Balzer, R.L. This Uncommon Heritage, supra at pp. 7, 15, 23, 24-28, 30, 56. That vineyard became the source of grape material, including Pinot blanc, "Pinot" Chardonnay and Pinot noir (Petit Pinot), for many other vineyards in California.

Several theories exist for the source of the French Pinot noir clones at La Cresta, including the vineyards of Burgundian winegrower Louis Latour (Masson's friend) or the vineyards at Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. 75 Haeger J.W. North American Pinot noir, supra at pp. 143-144. The Domaine de la Romanée-Conti is a Grand Cru vineyard for red wine situated in the commune of Vosne-Romanée in the Côte de Nuits subregion of Burgundy. The vineyards have produced some of the most expensive and highly regarded wines since before the French Revolution when Prince de Conti outbid Madame de Pompadour for the property. The precise origin of the Masson Pinot noir has not been documented.

Martin Ray was a stockbroker turned winegrower who became a protegé of Masson and purchased the Masson vineyards and winery in 1936. Ray created a new complex of five vineyards on a mountain top near La Cresta in 1945. Four of the new vineyards were planted exclusively to four wine varieties, Pinot noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay and White Riesling. La Cresta undoubtedly supplied cuttings for Ray's Pinot noir vineyard, although Ray's son Peter had travelled to France and visited vineyards to study French winemaking. There are some notes in Curtis Alley's files for the Carneros Creek Winery trials that Ray "sent his son to France [to] obtain a collection of Pinot noir out of Beaune" but no report that any grapes were retrieved and planted at Mt. Eden.

76 Ray, E. Vineyards in the Sky, supra at p. 209; handwritten notes on yellow papers, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 78: 19; and Martin Ray D-335, box 8: 17.

Ray prided himself on making 100% varietal wines, including Pinot noir, and waged a vigorous campaign against "sham varietals". 77 Balzer, L. The Wine Connoisseur, Home Magazine, Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1969; See Martin Ray Papers, UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Martin Ray D-335, box 2: 33. When the property that became Mount Eden Vineyards was controlled by Ray, the vineyards produced what were considered among the finest Pinot noir wines in California, notable for their "exquisite fruitiness and persuasive pepperishness". 78 UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Martin Ray D-335, box 2: 43.

After legal action that ended in 1971, stewardship of four of the five ranches developed by Ray on Mt. Eden in Saratoga passed to an entity called Mount Eden Vineyards, a winegrowing organization having no business connection with Ray. In 1974, Merry Edwards became the winemaker at Mount Eden Vineyards. 79 UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Martin Ray D-335, box 2: 43.

Around 1977, Merry Edwards at Mount Eden Vineyards donated the "Ray" Pinot noir clone to FPMS. It is not clear whether reference to that clone in the FPS database with the misspelling of "Rae" was intentional or inadvertent. In any case, the selection was sourced from the Mount Eden Vineyards developed by Martin Ray. The Goheen indexing binder at FPS identifies the material as "Rae 4W 11S", which began index testing in 1977. The selection underwent heat treatment therapy and was eventually released in 1988 as Pinot noir 37. Haeger reports that the clone has been widely propagated in California and is reputed to have small berries and clusters and deep and intense flavors. 80 Haeger J.W. North American Pinot noir, supra at p. 144.

Lytton Springs Heritage clone

Pinot noir 131.1 is a heritage selection donated to the public grapevine collection at Foundation Plant Services in 2014 by Ridge Vineyards & Winery. The material originated from their Lytton Estate vineyard which was planted in 1901 in Dry Creek Valley in Sonoma County, California. The vineyards and surrounding property at Lytton Springs are named after Captain William H. Litton who lived in Sonoma County in the 19th century. In 1860, Litton acquired a large tract of land between Dry Creek and Alexander Valleys north of Healdsburg. He built a plush resort on the property known as Litton Springs. Captain Litton sold the property in 1878 and it passed through various owners. The hillside vineyard blocks on the eastern portion of Lytton Springs were planted in 1901. The material that became Pinot noir 131.1 was collected from one of those blocks. After undergoing microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS, Pinot noir 131.1 qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2018.

Christina clone from Domaine Chandon

The Domaine Chandon Winery in the Carneros district of Napa Valley, California, donated a Pinot noir selection to Foundation Plant Services in 1996. They named it the Christina clone. The Christina clone may be Cristina 88 (formerly the Beringer selection) used in Marimar Estate wines. It is thought that Cristina 88 probably started out as one of the Martini clones distributed by FPS in the 1970's. 81 Haeger, John Winthrop, Pacific Pinot noir (University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2008), page 254. The original material tested positive for Rupestris stem pitting virus, which did not disqualify a selection from qualification in the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program. The original donated material was initially registered as Pinot noir 55. Later, a plant was produced from the original material using microshoot tip tissue culture therapy to eliminate the RSP virus. The new treated vine was planted in the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2000 as Pinot noir 87. Pinot noir 87 successfully completed testing under the 2010 Protocol and was planted in the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2011 as Pinot noir 87.1.

Vosne-Romanée clone

FPS was the beneficiary in 1999 of Pinot noir material that originated from the commune of Vosne-Romanée in the subregion of Côte de Nuit in Burgundy. Pinot noir FPS 122 came to FPS from a California vineyard, Pepe 7, where vines were grown from cuttings reportedly received from a Grand Cru vineyard in Vosne-Romanée. The original material underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2002 and was released as Pinot noir 122 in 2007.Geisenheim clones

Several Pinot noir clones in the FPS collection are associated with the viticulture program at Geisenheim University in Germany.Geisenheim Pinot noir clone 3/67-Z68 came to FPS from the Institute at Bernkastel, Kues/Mosel in 1968 (USDA Plant Identification number 325160). The selection was registered as Pinot noir 27 from 1974 to 1980, when it was removed from the foundation vineyard because it tested positive for Rupestris stem pitting virus. The selection underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy in 1999 and was released as Pinot noir 105 in 2003.

Pinot noir 127 came to FPMS in 1979 from Geisenheim, Germany via the former quarantine program at Oregon State University. The selection was initially known at FPMS by the German synonym name, Blauer Spätburgunder 01, and remained in the FPS quarantine vineyard GQ1 until 2010. The name was changed to the preferred prime name Pinot noir at that time when the selection was finally released as Pinot noir 127.

Frank Manty at Geisenheim University suggested that the Blauer Spätburgunder clone that OSU sent to FPMS in 1979 was most likely the same as clone 18 Gm at Geisenheim. Clone 18 Gm evolved from a group of clones originally developed by Professor Fritz Ritter, who was the Director of the Institute for Viticulture and Enology in Geisenheim from 1951 to 1964. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, Ritter created the new clones from an old Pinot noir selection at the Institute. Ritter’s clones were later adapted by the Geisenheim Institute for Grapevine Breeding and underwent a thorough clonal selection program in the 1960’s and 1970’s under the guidance of Professor Helmut Becker. Clone 18 Gm became famous for its “high yielding potential”. Becker distributed the clone in many Pinot noir regions, including Oregon. The clone produced compact clusters that could be problematic in humid areas, especially at the end of the growing season. 82 Email from Frank Manty (Hochschule Geisenheim University) to author, dated August 18, 2017.

Clones from Carneros Creek Winery Trial

Francis Mahoney was a pioneer in the development of Pinot noir clones for the grape and wine industry. He has owned and operated vineyards and a winery in the Carneros region of Napa County since the early 1970’s.

Mahoney was introduced to wine on a 1965 trip to Europe when he was 20 years old. He thereafter took a job at Connoisseur Wine Imports in San Francisco, which offered quality wines produced at the great estates in France and Germany. Experts from the University of Dijon visited and lectured on grape clones, particularly those used in the red wines of Burgundy. French wine producers appearing at the store would often refer to “the best clones” in the university collection in France. Mahoney discussed the wine industry with vintners such as André Tchelistcheff and Robert Mondavi, who invited him to the Napa Valley. Tchelistcheff recommended that Mahoney explore the “Carneros region” if he was interested in Pinot noir.

In the late 1960’s, there were only about 22 wineries in the Napa Valley, and large producers such as Christian Brothers and Beringer owned multiples of these. Cabernet Sauvignon was “the” wine in the Valley, followed by Chardonnay and Zinfandel. Many growers had Petite Sirah (pronounced “Peta Seres” at the time). Mahoney recalls that Cabernet Sauvignon grapes sold for around $400 per ton and that a bottle of the best wine in the Napa Valley, such as an aged Beaulieu Private Reserve, sold for about $5.00. The industry had yet to enter its Golden Age.

Mahoney’s family lived in Napa for a time when he was growing up, although they were not associated with the grape and wine business. His father helped build the California Veterans Home in Yountville and then moved the family to San Francisco. Mahoney became familiar with the Carneros region as boy from going picnicking and fishing with his father on the Napa River. He visited the Napa Valley in 1970 with an eye towards becoming involved in the production end of the wine business.

Mahoney and his wife Kathleen ended up moving to Napa by 1971. He identified a 200-acre horse property on Dealy Lane off Old Sonoma Road and bought the parcel in 1972 in a partnership with Balfour Gibson, his boss at Connoisseur. That original parcel was just down the street from the current site of Carneros Creek Winery.

Mahoney was impressed with the quality wines he had tasted from the Burgundy region in France. The wines were a complex mix of varieties and wine styles. He particularly liked Pinot noir, and “no one was doing it” in Napa, in part because the variety is a shy bearer and does not do as well in the heat of the Napa Valley. Mahoney decided that he would pursue making Pinot noir wine at his location in Carneros.

One of the people Mahoney consulted about options for Pinot noir budwood was the vineyard manager (1968-2000) for Trefethen Family Vineyards, Tony Baldini, who had done substantial research on planting vineyards and the available Pinot noir “selections”. Mahoney recalls that, unlike the French producers, no one in California used the word “clones” when speaking of the options for budwood. He tasted wines produced by Trefethen from various “selections” in their vineyard and observed apparent differences. Mahoney concluded that the source of Pinot noir budwood could have a significant effect on the resulting wine but was unable to identify any formal evaluations or comparisons for the selections available in California.

The Pinot noir vines at Trefethen Family Vineyards were later the source of Pinot noir FPS 102, although budwood from the Trefethen vines was not included in the trials conducted by Mahoney and UC Davis. Mahoney planted an 8-acre vineyard attached to his Carneros Creek Winery two years prior to beginning work on the Carneros Creek Winery Pinot noir study. The clonal material he planted in that 8-acre vineyard is known as the "CCW" clone, the standard Pinot noir clone still used at Carneros Creek Winery in 2017. Mahoney obtained the Pinot noir budwood for the CCW vineyard in 1973 from Baldini at Trefethen Vineyards. Although Mahoney was not aware of the exact identity of the Trefethen clone in the CCW vineyards until after the Carneros Creek Winery trial, the clone supplied by Baldini turned out to be a Pinot noir selection known as Martini 54. Mahoney donated the "CCW" clone to FPMS in 1996. [Martini 54 budwood from Stanly Lane vines was included as clone M (Pinot noir FPS 75) in the Carneros Creek Winery trial.]

Mahoney approached the experts at UC Davis, in particular Enology Professor Dinsmore Webb, with a proposal for a formal evaluation of Pinot noir clonal material, to be funded through a foundation associated with Balfour Gibson. Mahoney commented that it was difficult engaging the university because some experts (led by USDA-ARS Plant Pathologist Goheen) believed that “clones did not exist” and that differences resulted only from viruses. Another group (the Enology faculty) was more interested in how scientific methods could be used to manipulate particular results in wines. FPMS Manager and UC Viticulture Specialist Curtis Alley attended the presentation. He and UC faculty such as Harold Olmo were open to the idea of exploring inherent clonal differences within grape varieties. Alley ended up the lead researcher in the Carneros Creek Winery Pinot noir study.

When Mahoney and Alley began their clonal selection program at Carneros Creek Winery in Napa in 1974, their trial was the first comprehensive and controlled assessment of the best available clones for Pinot noir production in California. 83 Proposal for Clonal Selection Plot of Pinot noir clones at Carneros Creek Winery, Napa. UC Davis, Shields Library, Department of Special Collections, Olmo D-280, box 78: 19. The clonal evaluation would encompass 12 years and follow twenty Pinot noir clones from the vineyard all the way through wine making.

The university contributed eleven FPMS Pinot noir selections from the foundation collection to the clonal evaluation study. In the early 1970's, the FPMS grapevine collection contained almost 30 Pinot noir "clones" selected from the better California vineyards known for producing quality wines. The “clones” originated from vineyards and clonal programs in Europe and from old UC vineyard plantings on the Davis campus and in Amador County. Most of the selections in the FPMS program had been chosen from a viticultural standpoint without the benefit of comparative evaluation of the wines made from the selections. The FPMS selections contributed to the study included those from Wädenswil, Pommard, Gamay Beaujolais, Foothill Experiment Station, Martini clone 58 (FPS 13, heat treated), and Geisenheim. Efforts were made to include both non-heat treated and heat-treated versions of FPMS selections to determine the effect, if any, of treatment on performance.

Some growers and winemakers in California favored their own industry clones over the FPMS selections for Pinot noir wine. Mahoney and Alley decided to focus on the best Pinot noir wines made in California at the time and select budwood from the vineyards used to produce those wines. Cornelius Ough and Harold Olmo also participated in the budwood selection process. Vines were selected all over the state from vineyards at noteworthy wineries. They marked, monitored, tagged (in June), reevaluated (in August) and selected the candidates over a period of two years. The researchers made field selections from balanced vines that seemed best at ripening the fruit. The group chose nine industry clones from commercial California vineyards, including Joseph Swan, Hanzel, Beaulieu, Chalone and Martini. The trial was begun prior to the arrival in the United States in the 1980’s of the Dijon clones and other French clones imported for use in sparkling wines. (see below). 84 Nelson-Kluk, S. Carneros Creek Clonal Trial, FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, October 2002, pp. 10-12.

Initially, the decision was made to maintain confidentiality as to the source information for the industry clones. In the early days of the study, growers and winemakers preferred to maintain confidentiality because the industry was very competitive; sharing budwood with competitors was done infrequently and reluctantly. Mahoney convinced the owners of the budwood for the commercial clones to participate in the evaluation by arguing that sharing the accumulated knowledge would benefit the entire industry. The clones in the trial were identified in code using single letters of the alphabet for anonymity in evaluation. Eventually, the industry contributors shared the information about what they knew about the origin of their Pinot noir vines, supplemented with information acquired by the university. Documents in the Olmo collection (D-280) at Shields Library, UC Davis, contain information on the background of the clones used in the Carneros Creek Winery trial. 85 UC Davis, Shields Library, Olmo collection D-280, box 78: 19.