Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis -

July, 2018

© 2018 Regents of the University of California

Chardonnay Flourishes in California

The Chardonnay grape of Burgundy and Champagne has long been a member of the wine aristocracy. The classic white wine grape, whose name means "a place of thistles" in Latin, traces its heritage to the Middle Ages and a small village of the same name in the Maĉon region of France. 1 Harold P. Olmo. Chardonnay, an ampelography prepared for the Wine Advisory Board, San Francisco, California, 1971. Chardonnay has maintained its place at the top of the white wine hierarchy for centuries, within the precise French winemaking tradition. The esteem with which the grape is held in France is reflected in a comment made by French novelist Alexandre Dumas, who was quoted as saying that Montrachet (one of the highest quality French Chardonnays) should be sipped only while kneeling with head bowed.

Chardonnay appeared in the New World in the late 19th century during the early days of the California wine industry. Uncertainty as to the precise time of its arrival is attributed to a combination of lack of knowledge about the variety and mislabelling of newly introduced Chardonnay grapes. Notwithstanding morphological and physiological differences, the Chardonnay variety has long been confused with the true Pinot blanc variety, and, on occasion, with Melon. 2 Pierre Galet. Grape Varieties and Rootstock Varieties, English edition, Oenoplurimédia sarl, Chaintré, France, 1998, pp. 73-74; Wine Grape Varieties in California, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Publication 3419, eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert, 2003, p. 45. The confusion in California was aggravated by alternate spellings and erroneous names for the variety, including Chardenai, Chardonay, Pinot Chardonnay, Pinot blanc Chardonnay, and White Pinot. 3 Olmo, 1971, supra.

Some sources indicate that Chardonnay was present in California by the 1880's. Wine historian Charles Sullivan wrote that Chardonnay was first imported by J.H. Drummond in 1880 and appeared in H.W. Crabb's nursery list in 1882. 4 Charles L. Sullivan. A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998), p. 62. Chardonnay appeared in the catalogue of the Barren Hills Nurseries of Felix Gillet in Nevada City in 1888-89.

In 1882, Charles Wetmore, the Chief Executive Officer of the California State Board of Viticultural Commissioners, imported Chardonnay budwood from Meursault in Burgundy and distributed it in the Livermore Valley, the site of Wetmore's own winery, La Cresta Blanca. 5 Gerald Asher. ''Wine Journal: Chardonnay: Buds, Twigs and Clones'', Gourmet, May 1990, pp. 62-66. In his "Ampelography of California" published in 1884, Wetmore noted that the Burgundy types of white wine were "represented only experimentally" in California. 6 Charles A. Wetmore. ''Ampelography of California'', Part V. of Second Annual Report of the Chief Executive Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners for the Years 1882-3 and 1883-4, published in 1884, pp. 103-151. There were very few plantings of the noble white grapes of Burgundy and Champagne in the state at the time. 7 Wetmore, ''Ampelography of California'', supra, at pp. 111-112. Chardonnay was not mentioned by name in Wetmore's "Ampelography". In his 1884 Report to the Board, Wetmore proposed the use of the "Chardenai" grape and other noble varieties for production of "good sound commercial wines" in California. 8 Charles A. Wetmore. Second Annual Report of the Chief Executive Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners for the Years 1882-3 and 1883-4, published in 1884, Sacramento, California, p. 44.

Chardonnay vines were present in University of California vineyards in the late 19th century. 9 Olmo, 1971, supra. The Report of Viticultural Work to the Regents of the University of California, published in 1896, showed that researchers Eugene Hilgard and Frederic Bioletti tested both Pinot blanc and Chardonnay grapes (under the name "Pinot blanc Chardonnay", also known as Melon) sent to them from around the state. They found Chardonnay superior to Pinot blanc due to better bearing qualities, superior aroma and greater adaptability to various soils. The researchers believed that excellent Chardonnay wines could be made in some of the coast counties, especially in warm, well-drained locations in "late" [ripening] localities. 10 E.W. Hilgard. Report of the Viticultural Work During the Seasons 1887-93, with Data Regarding the Vintages of 1894-95 (part of the report of the Regents of the University of California) (Sacramento, A.J. Johnston, Superintendent, State Printing, 1896): pp. 199-201. There was limited interest in the variety in the state in the late 19th century, and the variety was used mostly as a base for sparkling wine for producers such as Masson and Korbel. 11 Olmo, 1971, supra.

Much of the current Chardonnay budwood in the Foundation Plant Services foundation grapevine collection originated from imports by California growers around the turn of the 20th century. The Wetmore budwood was an integral component of the well-known heritage Chardonnay material in the Wente family vineyard in Livermore. Wetmore distributed some of the budwood he brought to the Livermore Valley to the Theodore Gier vineyard at Pleasanton; Ernest Wente recalled that his primary source of Chardonnay for the Livermore vineyard was the Gier Vineyard. 12 Email communication to author from Philip Wente, Wente Vineyards, 2007; see also, Sullivan, supra, at p. 62. Wente also acquired Chardonnay from a second source during that period. A UC Davis employee (Leon Bonnet) persuaded Ernest Wente's father, Carl, to import some Chardonnay from the vine nursery of the wine school at the University of Montpellier in southern France around 1912. 13 Ernest A. Wente. ''Wine Making in the Livermore Valley'', an oral history conducted in 1969 by Ruth Teiser, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1971, at page 6-7; Asher, 1990, supra. The multiple sources of Chardonnay in the Wente vineyard came to be known collectively as the "Wente clone".

A third major source of Chardonnay grapes in California was an importation from Burgundy by Paul Masson for his La Cresta Vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains in 1896.

Notwithstanding the importations by California growers and wine evaluations at the university, UC researchers did not recommend that growers plant Chardonnay for wine making until after Repeal in 1933. In a 1907 university bulletin, Bioletti acknowledged Chardonnay among the group of quality grapes in the vineyards of the California coast ranges. He advised against planting that variety or any other light-bearing variety in rich valley soils. Bioletti stopped short of recommending Chardonnay in his list of white grapes recommended for the coast counties. 14 Frederic T. Bioletti. ''The Best Wine Grapes for California'', Calif. Agric. Exper. Sta. Bulletin No. 193 (Sacramento: W.W. Shannon, Superintendent, State Printing, 1907), pp. 142-143.

Bioletti authored a circular for the Agricultural Extension Service in March 1929 (rev. 1934) in which he assessed the performance of various wine grapes being grown in California at the end of Prohibition. He made no recommendations but noted that "Chardonay" [sic.] was the variety from which the famous white burgundies of Chablis, Meursault, and Montrachet were made. He observed that Chardonnay "bears better and makes a wine of higher quality in California than Pinot blanc. (North Coast region)." 15 Frederic T. Bioletti. ''Elements of Grape Growing in California'', Circular 30, California Agricultural Extension Service, University of California, Berkeley, March, 1929 (rev. April, 1934), p. 36.

Much of the Chardonnay that did exist in the state was destroyed during Prohibition because the thin skins of the delicate fruit could not withstand shipment to home winemakers on the East Coast, and the "musts" could not be adequately concentrated. 16 Olmo, 1971, supra. The result was that Chardonnay had a very limited presence in California vineyards in 1933 at the end of Prohibition. The only Chardonnay acreage with commercial potential in California at that time were the Wente and Masson vineyards.

Pre-WWII varietal studies beginning after Repeal at the University of California, Davis, resulted in a 1944 recommendation of Chardonnay as a desirable variety for producing quality table wine in the cooler regions of the state, namely, Winkler climate regions I and II (Central or North Coast regions) and "tentatively" for region III (Livermore Valley). 17 . M.A. Amerine and A.J. Winkler. ''Composition and Quality of Musts and Wines of California Grapes'', Hilgardia 15 (6): 533-534, 541-542 (1944). Post-WWII studies affirmed the prior findings and led Maynard Amerine and Albert Winkler to conclude that the quality of Chardonnay wine was "uniformly high in cool regions and often exceptional even in warmer regions". They recommended the judicious use of "good yielding clones for regions I and II". 18 Maynard A. Amerine. ''Chardonnay in California'', in the Focus on Chardonnay Journal, Spring 1990, Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards, p. 3; M.A. Amerine and A.J. Winkler. ''California Wine Grapes: Composition and Quality of their Musts and Wines'', Calif. Agric. Exper. Sta. Bulletin 794 (1963): pp. 14-15 (update of 1944 publication from Hilgardia).

One of the strengths of Chardonnay is its malleability - it adapts and thrives in diverse climates and in a wide range of soil types. Vine yields vary considerably from 2 to 8 tons per acre by climatic region, clonal variation and viticulture practices. 19 Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003, supra, at pp. 45-47. Chardonnay thrives in cool districts such as Winkler region I, where it produces lighter, crisper more neutral wines with higher acidity, which are frequently used in sparkling wines. However, Chardonnay vines leaf out and bud early and are susceptible to damage from early spring frosts, which can be a disadvantage in the cooler areas. Amerine and Winkler found that Chardonnay excelled in the warmer areas where the fruit ripened more fully in the longer growing season and produced higher flavored wines than in the cooler areas. 20 Olmo, 1971, supra; Amerine, ''Chardonnay in California'', 1990, supra, p. 3.

The university published bulletins and circulars containing their recommendations and distributed them widely throughout the state. Amerine and Winkler travelled extensively lecturing county farm advisors, growers and winemakers on the non-recommended and recommended varieties for each area. Notwithstanding the extensive publicity, there was still a hesitancy to produce much Chardonnay wine in the 1950s. The variety demonstrated low fruit yields and frequently suffered from viruses in California. Poor vineyard practices and wine making techniques resulted in low quality wines. The wines that were produced were usually mislabeled as Pinot chardonnay. 21 Amerine, ''Chardonnay in California'', 1990, supra.

Chardonnay acreage was estimated at about 150 acres in California in 1960, mainly in Alameda and Napa counties. 22 Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003, supra, at pp. 44-46. An indication that Chardonnay remained a minor player at that point is the fact that, prior to 1968, Chardonnay acreage was reported in the agricultural statistics by the California Department of Food & Agriculture (CDFA) as part of the "Miscellaneous" category for white wine grapes.

The grape and wine industry showed an increased willingness to experiment with the Chardonnay variety in the 1960's. Davis experts Harold Olmo and Austin Goheen selected and tested promising California clonal material and subjected it to heat treatment to eliminate the viruses that impeded yields. The result was higher-yielding, virus-tested clonal material that produced effectively in various climate zones, including the warmer interior valleys in California. The reported Chardonnay acreage in California in 1968 was 986 bearing acres. By the mid-1970s, the acreage had steadily increased to a total of more than 10,000 acres (bearing and nonbearing), including all five California climate regions. 23 1988 California Grape Acreage Report, California Agricultural Statistics Service, Sacramento, California, published December 8, 1989. The increase in acreage during that period was attributed to improved clonal material, production efficiency and wine quality.

California's very young Chardonnay industry was about to be an unwitting participant in a controversy which would publicly challenge the high quality white wines of France. In 1976, a California Chardonnay startled the wine world when Château Montelena 1973 bested some of France's most prestigious whites in a low key blind tasting in a Paris hotel. NY Times reporter George M. Taber chronicled the event in his book, Judgment of Paris: California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting that Revolutionized Wine. Leading French wine experts awarded California Chardonnays four of the six top places in that tasting. All nine judges gave their highest scores for white wine to a California Chardonnay, either Chateau Montelena or Chalone. 24 Gerald Asher. ''The Judgment of Paris'', The Pleasures of Wine, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, California (2002), pp. 173-174; George M. Taber. Judgment of Paris, California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting That Revolutionized Wine (Scribner, Avenue of the Americas, New York, 2005).

Following the "Judgment of Paris" in 1976, California Chardonnay plantings increased exponentially. Chardonnay acreage quadrupled (from about 3,000 to 17,000 acres) between 1970 and 1980, and then expanded to 42,000 acres by 1988 to overtake France's total Chardonnay acreage. 25 1988 California Grape Acreage Report, California Agricultural Statistics Service, Sacramento, California, published December 8, 1989. The familiar "California style" Chardonnay wine - ripe, buttery, and "oakey" - was developed with use of riper grapes, acid-lowering malolactic fermentation and aging in oak barrels. The mania continued with a huge increase in planting of Chardonnay grapes in California, peaking in the mid-1990s. By the turn of the new century in 2000, Chardonnay was the state's most widely planted wine grape variety with a total acreage of 102,568 acres. 26 2000 California Grape Acreage Report, California Agricultural Statistics Service, Sacramento, California, published May 25, 2001.

The overproduction of Chardonnay and widespread success of the California-style wine made it fashionable for some wine drinkers to begin to complain about "flabby" or "fat" Chardonnays and to boycott ("Anything But Chardonnay") the variety as passé. Chardonnay producers responded to the criticisms with a popular crisp new style involving fermentation in steel barrels and high acidity, offered as an alternative to the full, rich, oaky version. The discussion continues today among wine makers and wine drinkers as to which style shows the grape to its best advantage. Chardonnay continues to survive its critics.

In 1991, DNA fingerprinting performed on Chardonnay revealed that one parent of the noble grape was a viticultural "commoner". Microsatellite analysis showed that the parents of Chardonnay were the Pinot grape and nearly-extinct Gouais blanc, both of which were widespread in northeast France in the Middle Ages. The Pinot parental line offers a possible explanation for the longtime misidentification of Chardonnay as the "white Pinot".

It is theorized that Gouais blanc vines were in northeast France as a result of a gift in the 3rd century to what was at the time Gaul by Probus, a Roman Emperor from Dalmatia. Gouais blanc is the same variety as "Heunisch weiss" which was previously grown in Eastern Europe as "Belina Drobna". The lack of respect which the French had for the Gouais grape is illustrated by the fact that the name was “derived from an old French adjective "gou" - a term of derision". The Gouais grape was grown by peasants on land not considered acceptable for a Pinot or other noble grape. Gouais blanc is no longer planted in France. Famous siblings from the same fertile Pinot by Gouais blanc cross include Aligoté, Melon, and Gamay noir. 27 John Bowers, Jean-Michel Boursiquot, Patrice This, Kieu Chu, Henrik Johansson, and Carole Meredith. 'Historical Genetics: The Parentage of Chardonnay, Gamay, and Other Wine Grapes of Northeastern France', Science, 3 September 1999, at page 1562. [See the Pinot chapter for a discussion of the Gamay noir variety in California].

Chardonnay has persisted atop the white wine hierarchy amid the challenges and surprises. The variety is successful in multiple climates, soils, and winemaking styles because of its adaptability. As of 2017, Chardonnay continued to be the most widely planted wine grape in California. It remains the most important premium white table wine variety in the world.

FPS Chardonnay selections from California

Traditional Chardonnay grape clusters are small to medium size and cylindrical. The berries are small and round and have thin skins. Chardonnay often suffers from millerandage, a combination within a cluster of regular and small size berries known as "hens and chicks" or "pumpkins and peas". 28 Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, José Vouillamoz. WINE GRAPES (HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2012): p. 222; Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003, supra.

A second type of Chardonnay differs from the traditional form in flavor profile. Clones known as Chardonnay musqué are an aromatic subvariety of Chardonnay that has a slight muscat flavor, probably caused by an accumulation of monoterpenes during fruit maturation. 29 Andrew G. Reynolds, James Schlosser, Robert Power, Richard Roberts, James Willwerth, and Christiane de Savigny. ''Magnitude and Interaction of Viticultural and Enological Effects. I. Impact of Canopy Management and Yeast Strain on Sensory and Chemical Composition of Chardonnay Musqué'', Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 58: 1 (2007).

A third Chardonnay variant was selected by Harold Olmo for larger clusters with more uniform berry size and then subjected to heat treatment therapy at FPS. The final Chardonnay variant is a rare pink mutant called Chardonnay rosé.

Distinctions between clones are manifested by subtle morphological and biochemical differences. Researchers have proved that clonal diversity within ancient winegrape cultivars such as Chardonnay has a genetic basis accounted for "by the differential accumulation of somatic mutations in different somatic lineages". 30 Summaira Riaz, Keith E. Garrison, Gerald S. Dangl, Jean-Michel Boursiquot, and Carole P. Meredith. ''Genetic Divergence and Chimerism within Ancient Asexually Propagated Winegrape Cultivars'', J. Amer. Soc .Hort. Sci. 127(4): 508-514 (2002). Chardonnay is very adaptable to many climates and soils; clonal variation can result over time when plant material from the same source is dispersed to various climate and topographical regions throughout the state. Several researchers have observed differences in Chardonnay clonal selections, manifested in yield, vigor, fruit intensity and composition and flavor profiles. 31 Larry Bettiga. ''Comparison of Seven Chardonnay Clonal Selections in the Salinas Valley'', Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 54(3): 203-206 (2003); Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003, supra.

The California wine industry began to develop Chardonnay as a "wine varietal" in the post-WWII period. The clones used by the industry originated from two primary sources - the Wente family vineyard in Livermore and the Paul Masson vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Formal grape clonal selection programs in the United States have not received the financial support that has allowed European programs to progress. Despite this limitation, Harold Olmo at UC Davis was able to make a significant contribution to Chardonnay clonal selection in the late 1950's. He had observed that the Chardonnay plant material available in California at that time produced low yields with shot berries and viruses. Olmo attributed the state of the plant material to the lack of interest in the variety by the California grape and wine industry. 32 Harold P. Olmo. ''Clonal selection in the vinifera grape: Chardonnay'', paper presented at ASEV meeting (~1980); in files at Foundation Plant Services, University of California, Davis. He conducted Chardonnay trials at Louis Martini's Carneros vineyard and at the University's Oakville Experiment Station vineyard in the 1950's and 1960's and identified several selections for virus elimination treatment at FPS.

The term "Wente clone" is pervasive in the Chardonnay story because many growers, as well as Olmo, obtained budwood either directly or indirectly from the Wente vineyard in Livermore. As noted previously, there were two separate French sources of Chardonnay grapes for the vines in the Wente vineyard. Philip Wente, winegrower and co-owner of Wente Vineyards, commented: "The primary interest in obtaining wood from [the Wente] vineyard was that it had been continually selected by Ernest Wente for vines showing desirable traits and replicated in different new vineyard selections over 30 to 40 years. That wood was non-existent in the few other Chardonnay vineyards in the state at the time. CDFA records indicate around 230 acres of Chardonnay in California in 1960, so there were most likely only a few growers . . . our records showed Wente with about 70 acres at that time". 33 Philip Wente, personal communication with author, 2007.

Distinct clonal lines emerged from the selections harvested from the heritage Chardonnay vines in the Wente vineyard. The term "Wente clone" has been used both for an older selection with small clusters that sometimes contain a high percent of shot berries (often called "old Wente") and for the higher yielding FPS heat-treated selections that can be traced back to the Wente Vineyard. 34 Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003, supra. The "old Wente" clone is notable for its frequent "hens and chicks" berry morphology and clonal variation in flavor and aroma. 35 Gerald Asher, 1990, supra. The heat-treated UC selections developed from the Wente grapes do not exhibit the millenderage ("hens and chicks") tendency. Some of the clonal variants derived from the Wente material are known by names such as Robert Young, Stony Hill, and Curtis clone(s). Chardonnay-musqué style Wente variants include Spring Mountain, See's, Sterling and Rued.

Two of the first to propagate vineyards directly from the Wente vineyard were Fred and Eleanor McCrea, who harvested wood from the Livermore vineyard in 1948 for their new vineyard at Stony Hill above the Napa Valley. 36 Letter from Virginia Cole, Sebastiani Vineyards, to Jim Wolpert, Extension Specialist at UC Davis, dated November 24, 1992, from FPS files; Gerald Asher, 1990, supra. With the permission of Herman Wente, they took cuttings "at random" from a great number of Chardonnay vines throughout the Wente vineyard. The McCreas then planted the wood at their Stony Hill vineyard in St. Helena. They were early pioneers in Chardonnay planting in California, at a time when only about 225 acres of Chardonnay were planted in the state. Later, others such as Louis Martini and Hanzell took Wente clone wood from the McCreas' Stony Hill vineyard. 37 Eleanor McCrea. ''Stony Hill Vineyards: The Creation of Napa Valley Estate Winery'', an oral history conducted in 1990 by Lisa Jacobson, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1990.

In 1942, Louis Martini Jr. purchased 200 acres of the Stanly Ranch in Carneros, Napa, and years later began clonal experimentation with several varieties, including Chardonnay. The name "Stanly Lane" referred to the historic ranch of Judge John Stanly. Martini harvested wood that he referred to as the "Wente clone" from the McCreas' Stony Hill Chardonnay vines for planting at the Martini Stanly Lane vineyard in 1951 or 1952. He selected 30 individual vines at Stony Hill and budded 20 grafts from each of the 30 vines onto St. George rootstock. He later allowed UC Davis to use these 600 vines for trials. 38 Olmo, 1980, supra; Winter, Mick. The Napa Valley Book: Everything You Need to Know About California's Premium Wine Country. 3rd ed. (Westsong Publishing. Napa, California, 2007).

Heat-treated Wente Clones

Olmo began clonal selection of Chardonnay for the UC Davis collection in the early 1950's. His goals were to improve yield, eliminate the shot berry quality of many Chardonnays, and select against vines that appeared to be infected with virus. After measuring vine yields and making small wine lots in glass from the vines in the Martini vineyard for a number of years, Olmo chose the university's Chardonnay selections from the Stanly Lane vines beginning in 1955. The wood for what was later to become FPS selections 04-08 and 14 (the "Martini selections") was taken from the Stanly Lane vineyard in Carneros. 39 Olmo, 1980, supra.

The following image is a slide found in a file of papers at Foundation Plant Services with the label "LM Martini Clones Chardonnay Stanly Ranch".

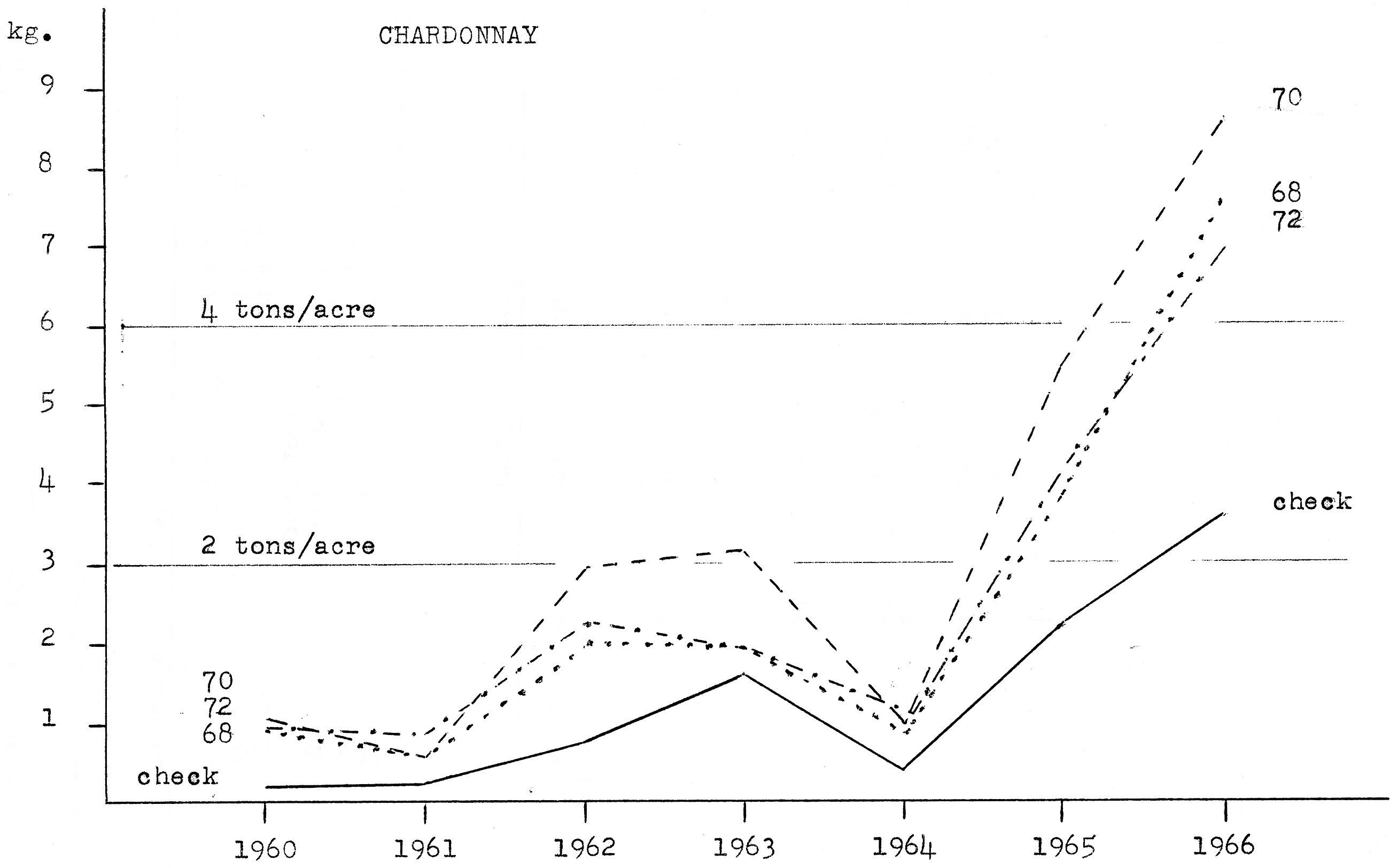

Olmo then advanced three of the Martini selections (Olmo's numbers #68, #70, and #72) to field and wine trials at the UC Oakville Experimental vineyard from 1960 to 1966. He compared them to one clone obtained from Meursault, France (Olmo import number 812) and two clones from Alsace, France (selections 430 and 439). In the Oakville trials, the Martini selections yielded as much as 5 tons, which was 2 to 3 tons per acre more than selections 430, 439 and 812. The latter three clones were abandoned long ago by FPS. 40 J.A. Wolpert, A.N. Kasimatis, and E. Weber. ''Field Performance of Six Chardonnay Clones in the Napa Valley'', Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 45 (4): 393 (1994); Austin Goheen, ''Chardonnay'', 1986, unpublished paper on file at FPS; Olmo, 1980, supra.

In 1964, Olmo took the initial group of Martini selections to FPS in Davis for heat treatment to rid them of any virus. The issue of whether heat treatment therapy eliminated virus was not well-settled at that time. USDA-ARS Plant Pathologist Dr. Austin Goheen explained in a 1985 letter: "Chardonnay became one of the first cultivars to test out the possibility of thermotherapy. We took the best appearing vines and heat treated them. From the explants that we obtained we indexed several lines. One line, which indexed disease-free and which was easily recognizable as a good Chardonnay, was registered in the California Clean Stock program". 41 Letter from Austin Goheen to Herman O. Amberg, Grafted Grapevine Nursery, New York, dated August 6, 1985, on file at FPS.

In total, Olmo submitted his Martini selections #65, #66, #68, #69, #70 and #72 to FPS for heat treatment. Vines produced from single buds that were heat-treated were given unique selection numbers, even if the buds were taken from the same original parent plant. For example, FPS selections 06 and 08 were both propagated from the same source vine (Olmo #68) at the Stanly Lane property. The difference between the two selections is that they were subjected to heat-treatment for different periods of time. The heat-treated Martini Chardonnay selections released to the public through the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program are sometimes known as the "heat treated Wente clones".

The Martini/ Olmo selections eventually became the most widely planted Chardonnay clones in California. Data developed during the replicated trials at the Oakville Experiment Station from 1960 to 1966 show that the Olmo Chardonnay selection program substantially increased the yield of three Olmo selections from 0.5-1.0 kg/vine to over 7 kg/vine and from 1.0 ton/acre to more than 7 tons/acre. 42 Olmo, 1980, supra (chart and diagram attached to paper on file at FPS, entitled ''Summary of Mean Yields, Oakville, 1960-1966'').

Chardonnay FPS 04 (formerly Olmo #66) and FPS 05 (formerly Olmo #69) were two of the selections Olmo submitted to FPS from the Martini Carneros vineyards. The two selections were taken from different mother vine sources at Stanly Lane. Both selections underwent heat treatment for 90 days at FPS. Chardonnay 04 and 05 successfully completed testing at FPS and attained registered status in the California Registration & Certification Program in 1969.

Prior to the time Chardonnay FPS 04 and 05 were released as registered plant material, then-FPMS Manager Curtis Alley combined the two selections into what he called "superclone 108". Goheen reported that "some nurserymen in the California program or Alley himself may have mixed Chardonnay 03A (which had shot berries) with #108 also". Although composed of two separate vine sources, superclone 108 was also known collectively in the industry as "Clone 108", the "Davis clone" and the "Wente clone". The material was distributed throughout the 1960s and used to plant most of Washington State's and half of Napa's Chardonnay. 43 Austin Goheen. ''Chardonnay'', Spring 1986, unpublished paper on file at FPS; Asher, 1990, supra. FPS 04 and 05 were later released separately, and Chardonnay 03A was discarded due to poor fruit set (see below).

Wente Vineyards was one of the early recipients of the heat-treated derivative of the old Wente clone for their new property in Monterey County. FPS and Wente Vineyards' records show that FPS sent budwood from location G9 v5-6 to Wente in 1963. The budwood at that location was known at the time as "clone 108" but was later more specifically identified as Chardonnay 04 when the two selections were separated in 1969. Wente planted "clone 108"/Chardonnay FPS 04 in their new increase block 36 at Arroyo Seco.

Chardonnay FPS 06 and FPS 08 (both formerly Olmo #68) were taken from the same vine at the Martini vineyards in Carneros but were given different FPS selection numbers because they underwent heat treatment for different lengths of time (06 for 164 days and 08 for 114 days). FPS 06 was the highest yielding selection (over 4 tons/ acre) of the Stanly Lane vines that underwent field trials with Olmo in the late 1950s. Both FPS 06 and FPS 08 first appeared on the list of registered vines in 1973.Chardonnay 09, 10, 11, 12 and 13 were all propagated from Chardonnay 08 in the late 1960s. FPS 09 and 10 underwent heat treatment for 102 days, FPS 11 and FPS 12 for 116 days, and FPS 13 for 144 days. They were all released in 1973.

Chardonnay 14 (formerly Olmo #65) came to FPS from the Martini Stanly Lane vineyard via a Viticulture Department vineyard at UC Davis' West Armstrong tract in the late 1960s. The selection was subjected to heat treatment for 111 days and was released in 1974.

Although widely planted on the West Coast, the "Davis clones" have been criticized by some winemakers who feel that a healthy yield capacity is inconsistent with the production of high quality wine. Others believe that the Davis plant material ("clone 108") is desirable as long as the crop is controlled by holding yields to a certain maximum amount (3 or 4 tons per acre). 44 Asher, 1990, supra. The following statement appeared in Wine & Spirits Magazine in April, 1994:

The following opinion about Chardonnay 04 appeared in Trellis Talk in June, 2000:

The FPS "Martini" selections (Chardonnay 04, 05, 06, 08, 14) and their propagative offspring (Chardonnay 09-13) have undergone several field trials to assess their performance in various California climate zones. Chardonnay 04 and 05 have been the Chardonnay workhorses in the state since they were distributed together initially as "clone 108". Either FPS 04 or 05 is invariably included in every California study of Chardonnay selections.

UCD researchers conducted field trials at two sites in the Napa Valley (Jaeger Vineyards; Beringer Vineyards) in 1989-1991. The purpose was to evaluate clonal differences among six certified, virus-tested FPS selections (Chardonnay 04, 05, 06, 14, 15, 16). Only clones testing free of virus were used to ensure that observed differences were genetic and not due to virus status. Both FPS 04 and 05 had characteristically high yields with large numbers of heavy clusters and high numbers of moderately heavy berries per cluster. FPS 06 yielded more, but lighter, clusters with fewer berries per cluster than FPS 04 and 05. FPS 06 and 15 (which will be discussed thoroughly below) exhibited the highest pruning weights at both sites. 47 Wolpert et al., 1994, supra.

Field performance of the same six FPS Chardonnays plus FPS 09 was evaluated by UC Viticulture Advisor Larry Bettiga in the Salinas Valley, Monterey County, in 1994-1996, with similar results to the Napa trials. Chardonnay 04 and 05 again showed the highest yields, attributable to higher cluster weights, large berry size and weights, and higher numbers of berries per cluster. Titratable acidity was highest and pH lowest for selections 04 and 05; the later maturity of these selections had also been observed in prior experiments. That tendency to later maturity has ripening implications for cool climate areas with shorter growing seasons. Bettiga conducted the Salinas trial, as well as other extensive clonal evaluations of Chardonnay on the central coast of California through 2005. He concludes that Chardonnay 04 and 05 produce "pretty nice wine at consistent production levels" and remain the most popular Chardonnay selections on the central coast in 2014. 48 Larry Bettiga, 2003, supra.

FPS 06 and 09 originated from the same vine in the Martini Stanly Lane vineyard (Olmo #68) but underwent heat treatment for different periods of time. Bettiga included the two selections in the Salinas trial to assess the difference, if any, the length of heat treatment has on field performance. Pruning weights were highest for selections 06, 09 and 15, which was similar to the Napa trials, and those three selections were in a group with intermediate yields, fewer berries and clusters and lower berry weights than selections 04 and 05. FPS 06 and 09 showed modest yields with a higher number of smaller clusters per vine. However, no significant differences in yield, growth or other experimental parameters were detected between FPS 06 and 09, leading the researchers to conclude that the different heat treatment periods imposed on the two selections from the same source vine did not influence vine performance.

The heavy clusters driving the high yields exhibited by Chardonnay 04 and 05 in the cool-climate trials could be problematic in the warmer climate regions of California on the theory that large tight clusters could suffer more sour rot than smaller or lighter clusters. Approximately 7% of the state's Chardonnay is grown in the San Joaquin Valley.

Researchers in Fresno County evaluated the performance of Chardonnay 04, 06, and 15, along with two Italian clones and one French clone (discussed below) for performance in a warm climate. Data from 2000-2003 revealed a "strikingly significant" year by clone interaction greater than that seen in Napa and Salinas for yield and yield components for FPS 04 and 15. For three of four years, FPS 04 consistently showed the fewest and heaviest clusters; this result was attributed to having more berries per cluster. 49 Matthew W. Fidelibus, L. Peter Christensen, Donald G. Katayama, and Pierre-Thibaut Verdenal. ''Yield Components and Fruit Composition of Six Chardonnay Grapevine Clones in the Central San Joaquin Valley, California'',Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 57(4): 503-506 (2006).

The Fresno researchers found that Chardonnay 04 fruit had the most desirable fruit composition of the clones tested, with higher Brix, lower pH, and higher titratable acids. The longer growing season of the warm climate region favors the fruit in this late-maturing selection. However, FPS 04 and two others (FPS 20 and 37) had the highest incidence of susceptibility to sour rot. That trait is a major disadvantage for FPS 04 when grown in the warm climate area of the California Central Valley. The researchers ultimately recommended that growers in that region consider FPS 15 rather than FPS 04 for the Chardonnay planting.

Early Chardonnay clones at Davis

The initial list of registered vines for the California certification program was published in 1956. Four Chardonnay clones appeared on that initial list from the FP[M]S foundation vineyard located in the Armstrong tract at UC Davis. At that time, the foundation vineyard was located at "the intersection of S.P. R.R. and U.S. 40 in the old Agronomy field" on the UC Davis campus. Those early Chardonnay selections were Chardonnay-1, Chardonnay-2, Chardonnay 430, and Chardonnay 439. Chardonnay 01A, Chardonnay 02A and Chardonnay 03A appeared later between 1964 and 1966.

During the 1950's when the earliest foundation vineyard existed at the Armstrong block, the numbers 1, 2, and 3 were used for the FPMS Chardonnay selections. The foundation block at Armstrong eventually lost foundation status when FPMS moved to a newer foundation vineyard west of Hopkins Road in 1960. A numbering system was established to distinguish the selections planted in the new foundation block from the earlier selections. Chardonnay 01A and 02A were not the same as Chardonnay-1 and -2 from the Armstrong block. The "A" suffix was added to selections for the Hopkins Road foundation vineyard in order to prevent confusion and duplication. 50 Letter to David Adelsheim, Newberg, Oregon, from A.C. Goheen, Research Plant Pathologist, USDA ARS, dated January 14, 1986 [from FPS files].

Chardonnay-2from the early Armstrong vineyard was one of five clones selected by Harold Olmo 1951 from the Goute d'Or vineyard in Meursault, France. Olmo assigned importation identification number 812. He believed that 812 was one of the best of the Meursault clones that he collected. 51 Olmo, 1980, supra. Two selections from the Colmar station in the Alsace region of France, labelled Chardonnay 430 and 439, were also planted in the early Armstrong foundation vineyard in 1956. Although Olmo used those three French clones in his Chardonnay research trials at Oakville in the 1950's, all three selections were removed from the foundation collection in 1959.

Chardonnay 01A came to FPS in 1961 from Zeraida Fernandez-Montero, in Mendoza, Argentina. The selection entered the United States with the name "Pinot Chardonnay" and with USDA Plant Identification number 277333. Chardonnay 01A completed testing and appeared in the Hopkins foundation vineyard in 1964 at location FV C2v16. FPS 01A was distributed to Australia among other places. The vines for 01A were removed from the foundation vineyard in 1975 because the vines did not set fruit, although they had indexed free of known viruses.

The story of Chardonnay-1, Chardonnay 02A and Chardonnay 72

Chardonnay-1 is the only one of the early Chardonnay clones from the 1956 foundation vineyard at Armstrong tract that survives in the FPS foundation collection today. The clone has undergone several treatments and received multiple selection numbers along the way, including Chardonnay 02A and Chardonnay 72. The precise origin of the Chardonnay-1 clone is unclear due to incomplete and confusing records at UCD and FP[M]S.

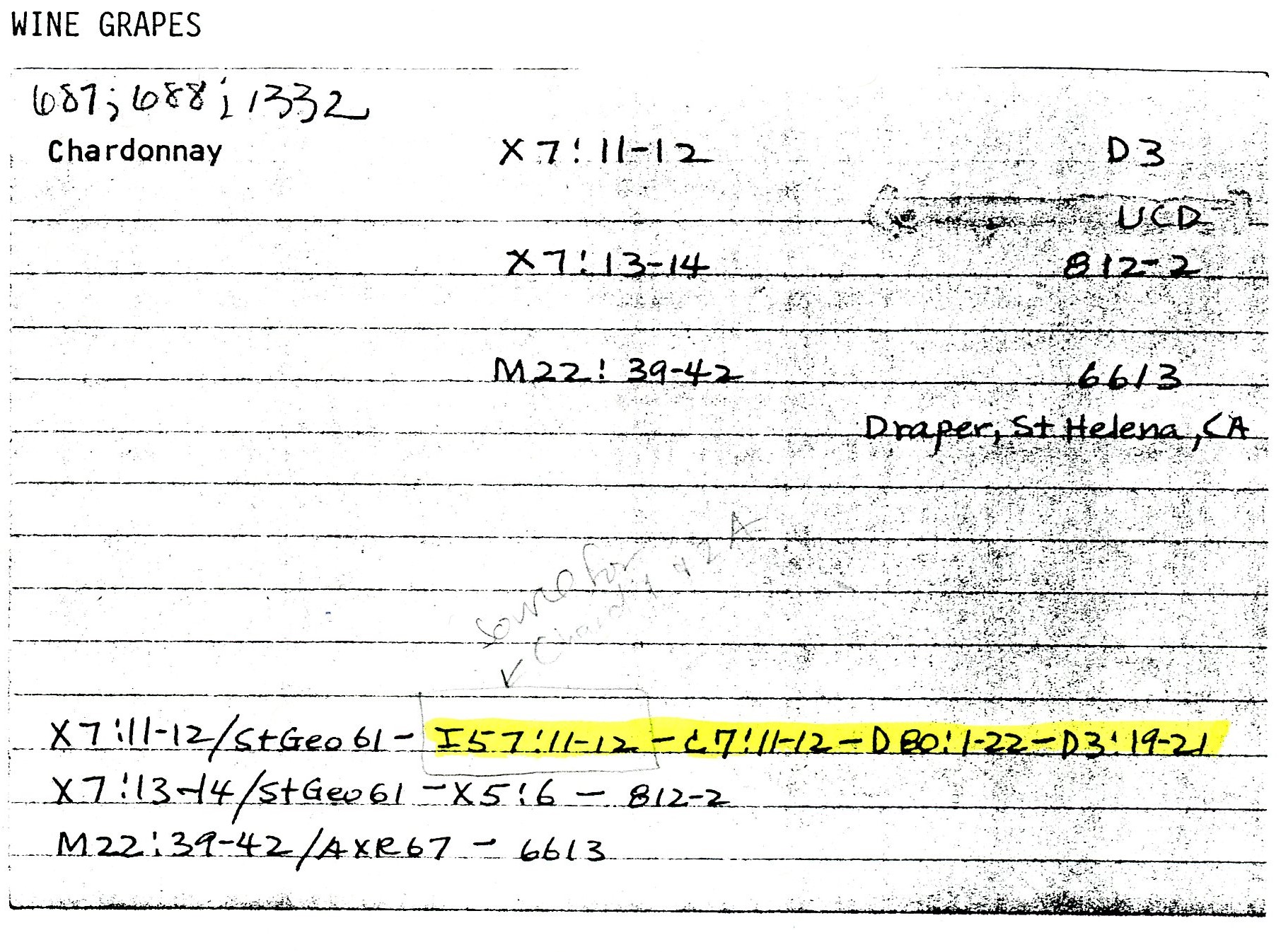

The 1956 list of registered vines published by the State of California Department of Agriculture (now CDFA) shows Chardonnay-1 planted in Block A (in the Armstrong vineyard), row 12, vines 9-12. The source of R12 v9-12 was shown as "I (eye) 57 v12 U.C.D." The disease indexing binder maintained by Goheen and his assistants at FPMS also showed the source of Chardonnay-1 (R12 v9-12) to be "I (eye) 57 v12".

"I 57-12, UCD" was a field location for a Chardonnay vine shown in the Department of Viticulture and Enology's Block "I" (eye) in old vineyard maps of the Armstrong tract. The vine at that location was part of the "W" (Wine Grape) Collection maintained by the Department on campus. The history of "I 57-12" can be tracked backwards in vineyard maps maintained by Olmo and the Department to a vineyard location on the UC Davis campus in the early 1930's.

Harold Olmo maintained an alphabetical list of varieties and locations from the Armstrong Vineyard in a small green binder dated November 1950. That binder ended up in the files at FPMS/FPS. The index in the binder shows Chardonnay at locations "I57, K118-122, and M147". The green binder is not complete but does have entries for vineyard locations in Blocks A-E.

A second vineyard map maintained by Olmo was entitled "Collection "W" (Wine Varieties), BLOCK I (eye)", which indicates that the vines were planted in that block in 1949. Locations I57v11-12 show a Chardonnay with source C7. Chardonnay at location C7 appears in section C of the little green binder. Those wine grape varieties in section C were "budded on 9/8-15/1944", according to the vineyard map. Chardonnay was planted in C7 at vines 11-12. The source of those vines was "D80: 1-22".

Section D of Olmo's little green binder shows a Chardonnay in row 80. The source of that Chardonnay was given as D3: 19-21. Another planting map from the Olmo papers in the Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis (D280, box 66: 1) shows a vineyard map of BLOCK D with a date of May 1, 1940. The map specifically states that the Chardonnay vines at D80 were budded August 27, 1936. The source of Chardonnay at D80 was again given as D3: 19-21.

Finally, the little green binder shows a Chardonnay at D3: 19-21. However, there was no source indication for the Chardonnay at that location. This author was unable to locate a document or record expressly stating the source information for "D3: 19-21". It is likely that the vines at D3: 19-21 were planted a few years prior to August of 1936 (when the propagation was made to D80).

Harold Olmo maintained records of his research on wine grapes in a card file, copies of which are on file at FPS. One of his cards containing Chardonnay selections shows source vines for I57: 11-12. The source history for that research selection (X7: 11-12) was noted by Olmo as: I57 v 11-12 < C7: 11-12 < D80: 1-22 < D3: 19-21.

The conclusion that can be drawn from the documentation outlined above is that Chardonnay-1 (source I57v12) originated from a vine that existed in the Armstrong Vineyard on the UC Davis campus prior to 1936 (D3: 19-21).

Old FPS distribution records from 1956 through 1961 show that the plant material described in the 1956 registered list as Chardonnay-1 was distributed to FPMS customers as "selection 1" until 1961. When a new foundation vineyard was started at FPMS in that year at a site west of Hopkins Road, plant material was taken from the old Chardonnay-1 vines to do heat treatment therapy prior to planting in the new vineyard. The selection Chardonnay-1 disappeared from the list of registered vines in 1963 and was removed from the foundation vineyard in 1967 due to leafroll virus.

The Chardonnay-1 material underwent heat treatment at FPMS in 1961 and 1962. Goheen documented the heat treatment therapy in the disease indexing binder and clearly indicated that the material from foundation vineyard location A12 v9 was excised and subjected to therapy. Block A was also referred to in the indexing binder as "A (O.F.)". The "old foundation" was the original A block at Armstrong tract on the Davis campus.

Both the list of registered vines at FPMS and the Goheen indexing binder show that the selection that was created from Chardonnay-1 using heat treatment therapy was renamed Chardonnay 02A. FPMS policy then and now was to give a selection created by disease therapy (e.g., heat treatment) a name distinct from the mother vine from which the selection was taken. Chardonnay 02A was planted in the new Hopkins foundation vineyard in 1964. The list of registered vines showed the source of Chardonnay 02A as "O.F. 12 v9 (heat treatment 102 days)". Subsequent registered lists gave the source as "O.F. R12v9 (I57v12), H102".

Efforts to further identify the source of Chardonnay-1 further back than location "D3: 19-21" in the Department vineyards in the early 1930's have been unsuccessful. Incomplete and ambiguous records have contributed uncertainty on the origin of the material which became Chardonnay-1 in 1956 and Chardonnay 02A in 1964. Several theories have been explored in an attempt to answer the question.

Confusion was generated by an erroneous statement in a 1986 paper supposedly authored by Austin Goheen that Chardonnay 02A was the "Meursault France (812) selection". That statement has been contradicted by the indexing records and lists of registered vines. Olmo's research records indicate that I57v12 (D3) and 812-2 (the Meursault selection) were separate selections. More importantly, the Meursault selection did not arrive at UCD until 1951, well after the plantings in the Department vineyards that resulted in I57v12.

It is possible that Chardonnay-1 evolved from the Chardonnay clones that had been planted in the older vineyards of the Department of Viticulture on the UC Davis campus. The Chardonnay at location D3: 19-21 (from which I57v12 originated) was in the Department vineyard prior to 1936. In that 1986 paper, Goheen also indicated that the university had mature vines of Chardonnay in the test blocks at Davis shortly after Repeal (1933). 52 Letter to Adelsheim from Goheen, 1986, supra. The fact that the vines were mature at that time suggests that the material was acquired before Harold Olmo began any formal collection or clonal development work at UCD.

UCD Department of Viticulture records do not clearly indicate the source of those "mature" vines that existed in the Department vineyards after Prohibition. Records do show that Chardonnay appeared in vineyards on campus prior to Repeal and had been acquired since Bioletti established the initial Department Variety Collection around 1910. Some of the Chardonnay planted on campus between 1910 and Repeal (1933) probably survived into the 1930's. There are several possibilities for the source of the Chardonnay vines that existed at location D3: 19-21 after Repeal.

Frederic Bioletti wrote notes on planting plans and maps when he began to install the vineyard at Davis in 1910. He prepared an initial planting map for the new vineyard that showed 53 rows on "Plot D" in a block entitled "Collection of vinifera varieties" (Department Variety Collection). "Pinot Chardonnay" appeared in row 1, vines 13-16. At the end of the Plot D map was the notation: "For rows 1-29: All cuttings from Tulare and planted March 1910 except where noted." 53 ''Davis Vineyard, Collection of Vinifera Varieties'', Plot D, page 10, Olmo collection, D-280, Box 2:11A, Special Collections Department, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

Bioletti's 1910 planting plan also contains one page that includes a list of candidate vines, including "50 Chardonnay cuttings" from the vineyard at Fountain Grove, Santa Rosa, California. 54 Page entitled ''Cuttings needed for Miscellaneous'', Davis Vineyard Maps and Plans, page 22, Olmo collection, D-280, Box 2: 11A, Special Collections Department, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. Bioletti's connection to Fountain Grove is explained in detail in the chapter on Malbec. Finally, a handwritten planting map for location D 44: 1-4 showed "Pinot Chardonnay" with no source information. No additional documents shed any light on which Chardonnay clones were planted in the Department of Viticulture's Variety Collection before Prohibition.

Olmo began his work selecting and evaluating clones when he was hired as a faculty member at UC Davis in 1935. He actively collected new clones in California and Europe, which he used in his Chardonnay development program. Those acquisitions in 1935 and after would have been too recent to qualify as the "mature vines" in the UC Davis vineyards at the time of Repeal.

Olmo initiated a system for cataloguing the grape introductions to Davis beginning in 1936, in which he assigned station numbers defining the year of introduction and vine number. 55 Harold P. Olmo. ''Plant Genetics and New Grape Varieties'', pages 88-89, an oral history conducted in 1972 and 1973 by Ruth Teiser, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1976. In April of 1939, Philippe Trinquet sent Chardonnay cuttings to Davis from the Experiment Station at Beaune in Dijon; those cuttings were assigned Olmo's station number 39131. 56 Grape Variety Introductions by the Division of Viticulture (H.P. Olmo), station number 39131, Chardonnay, source France, sender P. Trinquet, 4 cuttings, disposition 4/10/39; in file at FPS. That clone was used by Olmo in budding and grafting trials between 1939-1941 and appeared in Armstrong Vineyard Block B, in rows 59v5-6 and 138v29-30.

Olmo performed some clonal evaluation at the Wente vineyards in Livermore in the 1930's. Nothing in his research cards or file entitled "Clonal Selection (1935-1953)" suggests that he was looking at a Wente Chardonnay at that time. On the other hand, the file is clear that Olmo was evaluating Wente Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon vines in the 1930's. 57 Documents with maps and notations in the Olmo collection, D-280, Box 77: 10, Special Collections Department, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

Goheen noted that Olmo, in his early study of Chardonnay clones, made his selections in a commercial vineyard near Saratoga in Santa Clara County. Olmo himself wrote and spoke about his efforts to select Chardonnay clones for the university vineyards. He wrote that "clonal selection of Chardonnay was begun in 1951" when selections that were included in the Stanly Lane trials were made at Stony Hill in Napa (the McCrea vineyard) and the Martini Monte Rosso vineyard in Sonoma County.

As noted above, Olmo travelled to France in 1951 to collect the Chardonnay selections from Meursault and Alsace. 58 Olmo, 1980, supra, p. 4. Olmo's work on Chardonnay selection beginning in 1951 began well after Chardonnay vines existed in the UCD Department vineyards in the first half of the 1930's.

Finally, one of the clones that appeared in Olmo's research cards was a Chardonnay from the Draper Vineyard in St. Helena, Napa, which he obtained in 1966 and assigned station number 6613. That selection came to Davis much too late to have been the source of I57v12.

A second theory exists for the source of Chardonnay-1. The oral tradition passed down through three generations of the Wente family indicates that the Chardonnay selection that came to FPS as Chardonnay-1 (and later became Chardonnay 02A and then Chardonnay 72) originated from vineyard selection efforts by the Wente family in Livermore. 59 Philip Wente, personal communication with author, 2007. The old records at FPS and in the Olmo collection (D-280) at Shields Library are silent as to whether the vines located at "D3: 19-21" and later "I 57-12" originated from the Wente vineyard in Livermore.

There is documentation that FPMS did at one time receive a Chardonnay selection that originated directly from the Wente Livermore vineyard. That selection, Chardonnay 03A, came to FPS around 1963 with a source designation of "Wente 6 v18" and "Wente 10 v27". Selection 03 was planted in the new Hopkins foundation vineyard (location FV C7 v9-12) in 1964 and appeared on the list of registered vines as Chardonnay 03. In 1965, the selection number was changed to Chardonnay 03A. Selection 03A was no longer on the list of registered vines as of 1966. FPMS continued to distribute Chardonnay 03A as late as 1968 and pulled the vines from the foundation vineyard in 1969. Chardonnay 03A may have been accidentally added to the mix for superclone 108 and distributed in Oregon at some time in the 1960's. Austin Goheen wrote in 1986: 'Chardonnay 03A was a selection from a commercial planting in Livermore Valley. It was abandoned in 1968 because it did not set normal fruit [it had shot berries]'. 60 Austin Goheen, 1986, supra.

Having said all of the above, no record was located by this author explicitly listing the source of the Chardonnay vines in Armstrong Vineyard at location D3: 19-21 (the source of I57v12), to which Chardonnay-1 and Chardonnay 02A can be traced.

Chardonnay 02A survived in the FPMS foundation vineyard into the late 1960's. Chardonnay 02A was distributed to FPMS customers in 1966 and 1967. The selection was removed from the list of registered vines in 1968 and pulled out of the foundation vineyard in 1969 due to a positive test for leafroll virus.

Records from both FPS and Wente Vineyards show that 19 budsticks of Chardonnay 02A were sent to Wente Vineyards in 1966. The Wente records indicate that the wood from those budsticks was planted in a production block near Greenfield in Monterey County. Ralph D. Riva, viticulturist for Wente in Greenfield, supplied a map of the Greenfield planting to FPMS Grape Program Manager Susan Nelson-Kluk in 1991, showing the "planting of the old 02A Chardonnay clone". Wente Vineyards distributed wood from its Monterey production blocks in the 1970's and 1980's. The Arroyo Seco appellation vineyard provided a rich source of Chardonnay plant material to many growers in the State of California.

Chardonnay 02A disappeared from the FPS foundation vineyard for a time but returned in the 1990's. Chardonnay 02A had been a popular and widely-used "clone" in the state but FPMS no longer had vines of Chardonnay 02A growing in the foundation block after 1969. FPMS had distributed Chardonnay 02A to Wente Vineyards in 1966. UC Viticulture Extension Specialist Jim Wolpert and Ralph Riva collaborated in 1991 to return Chardonnay 02A plant material to FPS. Wente donated a large amount of Chardonnay 02A wood, from a single vine, to FPS.

The Chardonnay 02A material grown in the Arroyo Seco vineyard resembled the "old Wente clone" of Chardonnay that was grown in many California vineyards. The 02A clusters were small with shot berries. Wolpert described the vines donated by Wente as "clean" (no obvious virus symptoms on the leaves), with uniform production and small clusters with frequent "hens and chicks" cluster form (millenderage). 61 James Wolpert, personal communication with author, 2007. Riva indicated that wine from the Chardonnay 02A selection possessed four main flavor components (apple, muscat, pineapple, and fruit cocktail) which resulted in a "very good Chardonnay". 62 Ralph Riva, personal communication with author, 2007.

The donated Chardonnay 02A material underwent microshoot tip tissue culture virus elimination therapy at FPS and first appeared on the list of registered vines in 2002 as Chardonnay 72. Chardonnay 72 is the most recent iteration of the old clone Chardonnay-1 from the UCD Department vineyard in the early 1930's.

The generous donation of Chardonnay 02A to FPS by the Wente family in 1991 resulted in the return of an important heritage Chardonnay selection that had disappeared from the FPS foundation vineyard in the late 1960's.

Other California clones

Robert Young clone

A popular Chardonnay clone at FPS is Chardonnay 17, which is from the Robert Young Vineyard in Alexander Valley. Its original source vines have often been referred to as "the Robert Young clone", which was planted with budwood brought from the Wente vineyard in Livermore in the 1960's. 63 Gerald Asher, 1990, supra. Chardonnay 17 is a proprietary selection held for Robert Young Vineyards. The original material underwent heat treatment upon its arrival in Davis in 1982 and first appeared on the list of registered vines in 1987.

Chardonnay 17 was included in the Chalk Hill trials in Sonoma County. The 1996 harvest showed that the selection had a moderate yield amounting to 6.5 tons per acre - higher yielding and with larger clusters than FPS 15 (Prosser, Washington). Chardonnay 17 had many small shot berries and showed some rot resistance. The researchers concluded that it might be suitable for cool climate areas and rot-prone sites. Data taken over a four-year period showed the following ranges for selection 17: °Brix 22.4-23.3; pH 3.30-3.44; and titratable acid levels in the low range at 5.7-7.9. Chardonnay 17 was considered one of the most promising selections in the trial because it consistently produced high quality wines over the years. 64 Eleanor Heald and Ray Heald. ''Farming Chardonnay clones to the optimum'', Chalk Hill Estate Vineyards & Winery, Practical Winery & Vineyards, March/April 1999, p. 31; Trellis Talk, supra.

Robert Mondavi

Robert Mondavi Vineyards made two of its Chardonnay selections available to the public through FPS. The selections came to FPS in 1995 and 1998, initially as proprietary material. Chardonnay 67 is Mondavi's version of the Wente clone. Chardonnay 106 originated from Mondavi's Byron Vineyards in Santa Barbara County. Both selections underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy and first appeared on the list of registered vines in 2002 and 2005, respectively. The two Mondavi selections were donated to the public collection at FPS in 2006.

Sterling Vineyards

Chardonnay 79 and 80 came to FPS in 1996 from Sterling Vineyards, which farms approximately 1,200 acres of vineyards throughout the Napa Valley. FPS Director Deborah Golino collected the plant material from one of Sterling's vineyards. The selections, described as Heritage Sterling muscat clones 1 and 3, consist of two Chardonnay musqué-type clones that were favored by both the winemaker and viticulturist and believed to possess unique qualities. Both selections underwent microshoot tip tissue culture treatment at FPS and appeared on the list of registered vines in 2002.

Chalk Hill

Chardonnay 97 is a proprietary Chardonnay selection held at FPS for Chalk Hill Estate Vineyards & Winery in Healdsburg, California. The selection originated from a vineyard planted in 1974 and exhibits cluster morphology similar to an "old Wente" field selection (loose clusters with many small shot berries). For that reason, Chalk Hill refers to it as the "Shot Berry clone". 65 Heald and Heald, 1999, supra. Chalk Hill's viticulturist Mark Lingenfelder indicated that Chalk Hill Winery still farms 13 acres of that original block planted in 1974, and it continues to be one of their best blocks in terms of wine quality. Chardonnay 97 came to FPS with virus in 1996 and subsequently underwent tissue culture therapy. It successfully completed disease testing in 2003. Chalk Hill has incorporated Chardonnay 97 into its ongoing trial of 17 Chardonnay clones begun in 1996 and intended to demonstrate the value of clonal diversity.

Kendall Jackson

Chardonnay 102 was donated to the FPS public collection in 1997 by Kendall-Jackson Vineyards, who refer to this selection as the "Z clone". The selection originated in Sonoma County and is described as an aromatic (muscat-type) Chardonnay in the nature of the Rued and Spring Mountain clones. Selection 102 underwent tissue culture therapy for virus elimination and first appeared on the list of registered vines in 2003.

The Hyde clones

An important group of Chardonnay clones donated to the FPS public collection in 2001 and 2002 promises additional clonal variety with aromatic overtones. Larry Hyde, a well-respected Napa grape grower who has developed a variety of Chardonnay clones over the years, donated six clones to the public through FPS and the California Grapevine R&C Program. The 130-acre Hyde vineyard in the Carneros region of Napa supplies grapes from their Chardonnay clones and other varieties to more than a dozen wineries, frequently resulting in high quality wines.

Larry Hyde and Aubert de Villaine (Co-shareholder/manager of the Société-Civile Domaine de la Romanée Conti) are partners in the winery Hyde de Villaine (HdV) in Napa. The Chardonnay grapes for their wines are carefully selected from older vines in the Hyde Vineyard, which are mostly the old Wente clone or the Calera clone. Both of those well-known clones are in the group that Hyde donated to the FPS public collection.

Chardonnay 112 is known as the "Hyde clone". The material donated to FPS was selected from a 20-year old block in the Hyde vineyard in Carneros. The clone is productive with high acidity. Larry Hyde explained that the grapes yield an unusual and unique complex flavor profile, characterized by "nutmeg as young wine, followed by a peach-like fruit flavor in one or two months". The original Hyde clone material suffered from corky bark virus, which he has accommodated by growing it on St. George rootstock. The clone underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS and successfully completed testing for the foundation vineyard in 2011.

Hyde donated several additional Wente-like Chardonnay clones to FPS and believes that they are each unique in terms of flavor profile. He obtained two of those selections from the former Linda Vista Nursery and characterizes them as "clean and heat-treated" Wente selections. One of the Linda Vista clones became Chardonnay 113 at FPS. Hyde states that the clone has been a favorite of some winemakers due to its small clusters of flavorful small berries. It was necessary to put Chardonnay 113 through tissue culture therapy due to leafroll issues. The second Linda Vista clone is now Chardonnay 115.1. The clone has "smaller clusters and poor set". The original material underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2009 after testing positive for leafroll virus.

Hyde obtained grapevine material from the Wente vineyard in Livermore in the early 1980's. That selection from the Wente heritage vineyard has been an important component in the Hyde de Villaine wines. Hyde donated the selection to FPS in 2002. The untreated Wente material exhibited small clusters and lower production. It was required to undergo microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS due to multiple viruses. The treated material successfully completed testing in 2014 and is now known as Chardonnay 116.1.

Chardonnay 107 was donated by Hyde to the Foundation Plant Services public collection in 2001. He identified the clone as the "Calera clone", which Hyde obtained in 1989. The origin of the Calera clone itself is unclear. Calera founder Josh Jensen worked the harvest at Domaine de la Romanée-Conti in 1970 and at Domaine Dujac in 1971. Some have speculated that the Calera clone originated from one of those vineyards. 66 See, e.g., Marq De Villiers, The Heartbreak Grape (HarperCollinsWest, 1994), page 71. The same issue has been raised about the Calera Pinot noir plantings. The Hydes value the Calera Chardonnay for its "peach, stone characteristics, nutmeg spice flavor and high acidity". The Calera clone ripens a bit later than the Hyde Wente clone, which gives a longer hang time and allows for staggered harvest for the two clones.

Finally, the sixth selection in the Hyde group is an aromatic (musqué-type) grape obtained by Hyde from the Long Vineyards in Napa. Zelma Long indicates that the Long Vineyard was planted above Lake Hennessey in the Napa Valley in 1966 and 1967, using a massal selection that the budder, Rudi Rossi, said was collected from the Martini Vineyards. Larry Hyde took cuttings from the Long vineyard for what is now Chardonnay 114.1. Ms. Long, who has made wine for Simi Winery from Hyde's "Long Vineyard selection" as well as wine from grapes from Long Vineyards itself, indicates that the two groups of wines show different character. A grape sensory analysis she conducted at Long Vineyards showed five different flavor expressions in those grapes: yellow apple; citrus; spicy apple (nutmeg & ripe apple); white fruit (pear); and muscat (with citrus overlay), each occurring in a different percentage in the vineyard. The yellow apple and the citrus were the most common expressions. Hyde donated the "Long Vineyards selection" to FPS in 2002, after which it underwent tissue culture therapy and was released in 2014 as Chardonnay 114.1.

California Mt. Eden clone

The FPS foundation grapevine collection also contains field selections that originated from a Chardonnay line not associated with the Wente Vineyard.

Paul Masson immigrated to the San Jose, California, area in 1878, and he established the La Cresta vineyard and winery in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Wine grapes have been grown in that mountain appellation region since the 1860's. Chardonnay's value as a base for sparkling wines was recognized by Masson and others at the turn of the century. Masson imported Chardonnay plant material from Burgundy around 1896. 67 Olmo, 1971, supra; Eleanor Ray, Vineyards in the Sky, the Life of Legendary Vintner Martin Ray, page 209 (Heritage West Books, 1993).

Martin Ray took Chardonnay cuttings from the Paul Masson property and planted them in 1943 in a new vineyard property on a nearby 2000-foot peak called Mt. Eden in the Santa Cruz Mountains. The Chardonnay from that vineyard became the "Mt. Eden clone". The clone has been described as "a low-yielding, virus-infected selection with small berries and tight clusters". 68 Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003, supra at page 47. Matanzas Creek Winery is one that has had success with that clone.

Chardonnay 27 and 28 were donated to the FPS public collection by Matanzas Creek Winery in 1984. Merry Edwards was the winemaker at both Mt. Eden Vineyards (1974-1977) and Matanzas Creek (1977-84) and took Mt. Eden plant material to Matanzas Creek. 69 Rod Smith, 1994, supra. The selections donated by Matanzas Creek to FPS were "Matanzas Creek Mt. Eden Vineyard clones 1 and 2". Both selections underwent 61 days of heat treatment at Davis. They first appeared on the list of registered vines in 1992 and 1994, respectively.

Simi Winery has produced quality wines with Chardonnay grapes that the winemakers believed to be the Mt. Eden clone. Chardonnay 66 was collected in 1994 by FPS Director Deborah Golino from a Chardonnay block that had been planted by Simi Vineyards around 1990, in a newly developed vineyard on Piner Road in the Russian River Valley. Simi acquired the Chardonnay plant material from grower Larry Hyde's vineyard in Carneros. There is ambiguity about the source of the material that went to the Simi vineyard. Simi staff believed that the material they obtained was the Mt. Eden clone. Hyde recently indicated that, to the best of his recollection, Simi harvested cuttings of the Calera clone from the Hyde Vineyards.

Golino, Zelma Long and Simi viticulturist Diane Kenworthy selected four vines from Simi's vineyard on Piner Road. One of those four vines evolved into Chardonnay 66. Upon its arrival at FPS, selection 66 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture treatment and later appeared on the list of registered selections in 1999.

Simi had previously made wine from the Hyde grapes and appreciated the wine for its intensity and depth of feel. 70 Diane Kenworthy, personal communication with author, 2007. Simi winemaker Long indicated that the vines from the Hyde vineyard were productive and of excellent quality and described the wine from the Hyde grapes as having "depth and power and texture". 71 Zelma Long, personal communication with author, 2007.

The Prosser clone from Washington State

Chardonnay FPS 15 was sent to UC Davis in 1969 by "the father of Washington wine", Dr. Walter Clore, of the Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Station (IARES) in Prosser, Washington. Dr. Clore was a horticulturist associated with Washington State University's Prosser Experiment Station for 40 years. He presided over field and wine trials for 250 grape varieties, including Chardonnay, and was primarily responsible for convincing Washington growers that premium wines could be made from vinifera grapes grown in Eastern Washington. Clore planted variety blocks at Prosser beginning in the late 1930's, using vinifera material that he and his mentor, Sunnyside farmer and winery owner W.B. Bridgman, imported from Europe and from California growers. 72 W. J. Clore, C.W. Nagel, and G.H. Carter. ''Ten Years of Grape Variety Responses and Wine Making Trials in Central Washington'', WSU Bulletin 823 (1976); Ronald Irvine and Walter J. Clore. The Wine Project – Washington State’s Winemaking History, Sketch Publications, Vashon, Washington (1997).

Chardonnay 15 is known in the State of Washington as "the Prosser clone". Other than a location designation, i.e., "Prosser LR 2 v6", the origin of Chardonnay 15 is not clear. The Clore variety blocks at Prosser were split into "High" and "Low" sections. FPS 15 was from row 2 vine 6 of the "Low" section variety block. The selection tested positive for virus at FPS and underwent heat treatment at Davis for 173 days, after which it was released in 1974. Chardonnay 15 been one of the most requested Chardonnay selections at FPS.

A 1-½ acre variety trial was established at the IAREC vineyard in 1965 using premium wine grapes, including Chardonnay; the analysis of the experiment does not report a source for the Chardonnay plants used in the trial but does indicate that the material in the trial was known to be infected with virus. Data on yields and fruit composition were reported for 1967-1970. The Chardonnay in the trial was one of the lowest yielding varieties (3.78-5.59 tons per acre) and had loose clusters and an excessive amount of shot berries. The selection was infected with leaf roll virus. Grape maturity and fruit analysis figures for the four-year period of the trials varied from: °Brix - 21.3 to 23.1 (which was within the range of FPS 15 in Fresno 22.8 and Salinas 23.2); percent titratable acid - 0.76 to 1.03 (higher than Fresno 0.58 and Salinas 0.65); and pH - 3.20 to 3.43.( higher than Fresno and Salinas, 3.70 and 3.61). 73 W. J. Clore, C.W. Nagel, G.H. Carter, V.P. Brummund and R.D. Fay. ''Wine Grape Production Studies in Washington'', Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 23 (1): 18-25 (1972). The grape morphology, timing of the Washington IAREC trial, and the fact that the Chardonnay in the trial was virus-infected suggest that this Chardonnay was the clone that eventually became Chardonnay 15.

Chardonnay 15 has been evaluated in numerous field and wine trials conducted in California. In addition to the trials mentioned above, UC Viticulture Extension Specialist Larry Bettiga began a second trial in Monterey County in 1995 near the city of Greenfield. Chardonnay 05 and 15 were used as standards to compare against some French and Italian clones. 74 Larry Bettiga. ''Evaluation of Chardonnay Clonal Selections'', 2002, an unpublished paper. Chardonnay 15 was also included in the Chalk Hill trial at Healdsburg, Sonoma County, begun in 1989. FPS 15 produced relatively low to moderate yields in all the trials. The researchers from several of the trials observed that Chardonnay 15 has looser clusters, smaller berries and earlier ripening.

Yields for the trials in the cooler growing areas were:

| County | Vineyard | kg/vine | Researcher(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Napa | Jaeger/Beringer | 9.3 | Wolpert et.al, 1994 |

| Sonoma | Chalk Hill | 4.94-8.12 | Heald and Heald, 1999 |

| Monterey | Salinas/Zabala | 3.83 | Bettiga, 2003 |

| Monterey | Salinas/Pacific | 6.79 | Bettiga, 2002 |

In the Fresno County trial, Chardonnay 15 yielded an average of 19.9 kg/vine for the four-year period, which was the lowest of the six selections tested. FPS 15 experienced erratic fruit yield over the years as indicated by significant year x clone interaction in some of the trials. The lower yields were attributed to lower cluster weights due to smaller and fewer berries per cluster. A large number of shot berries was reported in all the trials except for Fresno. In summary, although FPS 15 demonstrated high vine vigor in the trials, it produced lower yields due to higher numbers of smaller loose clusters.

The Fresno and Sonoma/Chalk Hill researchers found FPS 15 to be "sour-rot resistant" and "rot resistant", respectively. The Fresno researchers found 70-90% fewer clusters with sour rot in FPS 15 than with the other selections tested. The cluster morphology and sour-rot resistance led the Fresno researchers to recommend Chardonnay 15 for the warmer growing areas of the Central Valley. 75 Fidelibus et al., 2006, supra.

Chardonnay 15 has received good marks for fruit composition in some of the trials. The Fresno researchers concluded that FPS 15 had acceptable fruit quality due to fewer soluble solids and high titratable acidity. The conclusion from trials at Simi in the early 1990's was that Chardonnay 15 had a great "intensity" of fruity flavor, which could be excellent for blends. 76 Letter from Virginia Cole to Jim Wolpert, 1992, supra. The Chalk Hill researchers found FPS 15 to be one of the five most preferred clones in the wine tasting category of the trials due to consistent production of high quality wine over the years; FPS 15 was advanced to further trials at Chalk Hill. The researchers concluded: "[FPS 15] is projected to be ideal for cool climates and Reserve Chardonnay programs". 77 Heald and Heald, 1999, supra.

Oregon

In 2017, two Chardonnay clones from Oregon were released to the public grapevine foundation collection at FPS. Duarte Nursery supplied Chardonnay 133.1 from a vineyard in Oregon.

Chardonnay 143.1 was donated to the FPS public collection in 2012 by Jason Lett of the Eyrie Vineyards in Dundee, Oregon. The material is called the "Eyrie clone" of Chardonnay. The Eyrie clone was originally a field selection collected from the Draper Ranch in St. Helena, California, in 1964. The clone was planted on Eyrie Vineyards' property in Oregon and was thereafter selected and developed in that location. Lett reports that the Eyrie clone shows diverse cluster morphology. Some clusters show hen-and-chick characteristics; some are tighter and pyramidal with an even set; the remaining clusters are intermediate between the two. The original Eyrie clone material underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2014 and qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2017.

Chardonnay selections from France

ENTAV-INRA® Authorized French clones

Recent imports from Europe have increased the clonal diversity of Chardonnay plant material available in California. Chardonnay is the leading white wine grape variety in France, where it is grown in Burgundy, Champagne, the Languedoc and a few other areas. In the French system, clonal material undergoes extensive testing and certification. Some of the more popular of the certified French clones are ENTAV-INRA® 96 (most frequently propagated), 76, 95, 277 and 548. Clones 77 and 809 are French clones of the musqué type.

Three trademarked Chardonnay clones sent to FPS in 1997 were Chardonnay ENTAV-INRA® 76, 96 and 548. Laurent Audeguin, Development Manager for the ENTAV-INRA® trademark program, summarized the performance of the three FPS registered selections. ENTAV-INRA® 76 is a regular clone in terms of production and quality; the wines obtained are representative of the variety: aromatic, fine, typical and well-balanced. ENTAV-INRA® 96 demonstrates good vigor and a high level of production; the wines obtained are aromatic, elegant and sharp. ENTAV-INRA® 548 has lower than average production due to small and loose clusters with high sugar potential; the wines are aromatic, complex and concentrated with good length. Clone 548 became popular in the 1990's. All three selections have good ageing potential if yield is controlled.

Two additional ENTAV clones came to FPS in 2010. Chardonnay ENTAV-INRA® 809 originated from the Saône-et-Loire region in Burgundy and was registered in France in 1985. Chardonnay ENTAV-INRA® 1068 is from the Côte-d'Or region and was registered in 2003. Both clones exhibit muscat flavors and are used in varying amounts in white wine blends. Clones 809 and 1068 underwent tissue culture therapy at FPS to qualify for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard and successfully completed testing in 2014.

Chardonnay ENTAV-INRA® 1067.1 successfully qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2016. French clone 1067 originated from the Côte-d'Or region of Burgundy. According to Audeguin, the clone performs similar to Chardonnay 548.

Finally, Chardonnay ENTAV-INRA® 1066 came to the United States in 2007 and qualified for the FPS foundation vineyard in 2012. Clone 1066 originated in the Côte d'Or in Burgundy. Audeguin indicated that the clone exhibits loose and small clusters and the "hens and chicks" morphology known as millenderage. The clone has low fertility. ENTAV recommends that clone 1066 be used in blends because of the low production numbers.

Dijon clones

In the mid-1980s, the Oregon Winegrower Association and Oregon State University (OSU) collaborated on a project related to a mutual interest in European clonal material. Oregon growers had concluded that California Chardonnay clones (in particular, "selection 108", also known as Chardonnay FPS 04 and 05) did not ripen in a timely manner in their more northern climate.

David Adelsheim of Adelsheim Vineyard in Oregon and Ron Cameron at OSU worked together and successfully established relationships with Professor Raymond Bernard, viticulturalist and regional director at the Office National Interprofessionnel des Vins (ONIVINS) in Dijon, France, and Alex Schaeffer at the Station de Reserches Viticoles et Oenologiques, INRA, Colmar, France. The OSU program (no longer in existence) was able to import eight French Chardonnay clones selected by Bernard from Burgundian vineyards.

Mr. Adelsheim appeared in California at a 1985 meeting of University and grape industry personnel and explained the OSU importation project. In response to interest from the California grape and wine industry, OSU agreed to make some of the French Chardonnay clones (the "Dijon clones") available for the public collection at FPS in 1987-88.

The French clones sent to FPS from OSU are part of the public grapevine collection and considered "generic". The source for generic French clones is indicated on the FPS database using the following language: "reported to be French clone xxxx". This language is used to distinguish the generic clonal material from trademarked clones that are authorized by ENTAV and sent from the official ENTAV vineyards and from other sources. Generic clones are assigned an FPS selection number that is different from the reported French clone number. There is no guarantee of clonal authenticity for generic clones.