Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis -

December, 2018

© 2018 Regents of the University of California

Riesling at FPS

More than 50 entries appear when a cultivar name search is performed for the name "Riesling" on the Vitis International Variety Catalogue (VIVC) website (www.vivc.de). The "true Riesling" alone shows 120 synonyms on that same website. Name ambiguity has in the past interfered with a clear identity for the true Riesling. In the United States, white wines made in the German-style with cultivars other than Riesling were often given the Riesling name.

Riesling is versatile in terms of viticultural and enological traits. The cultivar is very sensitive to the climate and soil in which it is grown, resulting in distinctly different flavors in the wines. Riesling can produce wines that are dry, medium dry, medium sweet or sweet. Shifting wine preferences have prevented the cultivar from forming a clear impression on wine consumers, particularly in California.

The Riesling grape's popularity in California has taken an uneven course. Recent trends suggest that interest is again rising. The Riesling collection at Foundation Plant Services (FPS) offers some of the best clones from the old world as well as selections that originated in California vineyards over one hundred years ago.

The Identity Problem

The Riesling grape has a long and rich history in Germany, where it is grown along the Rhine River and its tributaries. Most authorities believe that the white wine cultivar originated in that cool temperate area around the Middle Ages.

Other grape cultivars, Riesling "imposters" and distant relatives of the true Riesling, have adopted the Riesling name in some form since that time to gain marketing advantage. The proliferation of names has resulted in confusion related to the identity of the true Riesling.

In 1998, scientists in Austria used DNA technology to create a partial identity for the "true Riesling". They were able to determine that one of its parents is Heunisch weiss, which is known in France as Gouais blanc. Riesling and Gouais blanc/Heunisch weiss share one allele at all loci. 1 Regner F., Stadlbauer A., Eisenheld C. and Kaserer H. 2000. Genetic Relationships Among Pinots and Related Cultivars, Am.J. Enol. Vitic. 51 (1): 7-14 (2000); Regner F., Stadlbauer A., and Eisenheld A. 1998a. Heunisch x Fränkisch, an important gene reservoir for European grapevines (Vitis v. L. sativa), Vitic. Enol. Sci., 53: 114-118 (1998) (in German).

Gouais blanc/Heunisch weiss is a late ripening cultivar that was able to flourish in northern Europe in the Middle Ages because of a 700-year warm climate phase at that time. 2 Jung, A. and E. Maul. 2004. Preservation of grapevine genetic resources in Germany, based on new findings in old historical vineyards, Bulletin de l’O.I.V. vol. 77: 883-884 (Septembre-Octobre 2004), text presented at the 84th World Congress of O.I.V. in Vienna, July 2004; Regner F., Stadlbauer A., and Eisenheld A. 1998a. Heunisch x Fränkisch, an important gene reservoir for European grapevines (Vitis v. L. sativa), Vitic. Enol. Sci., 53: 114-118 (1998) (in German). Although the variety produced wine of poor quality, that cultivar was an important crossing partner for wild vines and other grapevines in the cooler climates during that era. 3 Regner F., Stadlhuber A., Eisenheld C. and Kaserer H. 2000. Considerations about the Evolution of Grapevine and the Role of Traminer, Proc. VII Int’l Symp. on Grapevine Genetics and Breeding, Eds. A. Bouquet and J.-M. Boursiquot, Acta Hort. 528, ISHS 2000; Regner F., Stadlbauer A., Eisenheld C. and Kaserer H. 2000. Genetic Relationships Among Pinots and Related Cultivars, Am.J. Enol. Vitic. 51 (1): 7-14 (2000). Gouais blanc is a prolific parent and has produced dozens of French wine cultivars such as Chardonnay, Sémillon, Gamay noir, Melon and Aligoté.

There are multiple theories of origin for the Gouais blanc/Heunisch weiss cultivar. One theory is that Gouais/Heunisch was imported to Europe by the Huns from Hungary. The cultivar was known as vinum hunicum in the literature of the Middle Ages. 4 Regner F., Stadlhuber A., Eisenheld C. and Kaserer H. 2000. Considerations about the Evolution of Grapevine and the Role of Traminer, Proc. VII Int’l Symp. on Grapevine Genetics and Breeding, Eds. A. Bouquet and J.-M. Boursiquot, Acta Hort. 528, ISHS 2000; Regner F., Stadlbauer A., Eisenheld C. and Kaserer H. 2000. Genetic Relationships Among Pinots and Related Cultivars, Am.J. Enol. Vitic. 51 (1): 7-14 (2000).

Jancis Robinson and her colleagues propose in their WINE GRAPES book that it is more likely that Gouais blanc/Heunisch weiss originated in an area that includes "central north-eastern France and south-western Germany", an area of important biodiversity for the variety. 5 Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and José Vouillamoz, WINE GRAPES, pp. 419-420 (HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2012). The authors note that the region of Eastern Europe (including Hungary) was not a source of offspring from the Gouais/Heunisch variety.

The Austrian scientists were unable to identify Riesling's second parent. They did determine that that the second parent was a close relative of the grape variety Traminer (Savagnin blanc). 6 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 32-33 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016); Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and José Vouillamoz, WINE GRAPES, p. 889 (HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2012). The scientists speculated that Riesling originated by a probable cross of the Heunisch variety with the other main gene pool mentioned in viticulture during the Middle Ages, the Fränkisch pool (vinum francicum), which produced the variety Traminer. 7 Regner F., Stadlbauer A., and Eisenheld A. 1998a. Heunisch x Fränkisch, an important gene reservoir for European grapevines (Vitis v. L. sativa), Vitic. Enol. Sci., 53: 114-118 (1998) (in German).

The Fränkisch pool shows close genetic ties to some wild Vitis sylvestris genotypes, which are the wild type vinifera of the region. 8 Forneck, A., Walker M.A., Schreiber A., Blaich R. and Schumann F. 2003. Genetic Diversity in Vitis vinifera ssp. sylvestris Gmelin from Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, Proc. VIIIth IC on Grape, Eds: E. Hajdu & É. Borbás, Acta Hort 603, ISHS 2003; Regner, F., A. Stadlbauer, and C. Eisenheld. 2001. Molecular Markers for Genotyping Grapevine and for Identifying Clones of Traditional Varieties. Proc. Int. Symp. On Molecular Markers, Eds. Doré, Dosba & Baril, Acta Hort. 546, ISHS 2001. Vitis sylvestris existed and spread throughout western Europe for a very long time before cultivated grape varieties were imported to the region. It is not clear whether western European grape cultivars evolved from the local wild type or originated from imported cultivars. 9 Walker, M. Andrew, Professor, Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, 2009. Personal communication with author on September 24, 2009. One group of scientists has concluded that Riesling did not directly originate from a native wild grapevine. 10 Perret M., Arnold C., Gobat J.-M., and P. Küpfer. 2000. Relationships and Genetic Diversity of Wild and Cultivated Grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.) in Central Europe based on Microsatellite Markers, Proc. VII Int’l Symp. On Grapevine Genetics and Breeding, Eds. A. Bouquet and J.-M. Boursiquot, Acta Hort. 528, ISHS 2000

The Austrian scientists point to one of the representative grape cultivars of the Fränkisch gene pool, the grapevine known as Traminer, as a candidate for Riesling's second parent. Traminer shares enough alleles with the Vitis sylvestris population to indicate at least a close relationship between the two, if not parentage. 11 Regner F., Stadlhuber A., Eisenheld C. and Kaserer H. 2000. Considerations about the Evolution of Grapevine and the Role of Traminer, Proc. VII Int’l Symp. on Grapevine Genetics and Breeding, Eds. A. Bouquet and J.-M. Boursiquot, Acta Hort. 528, ISHS 2000. Traminer was distributed throughout northern Europe by the Romans and provided a higher quality wine in terms of better sugar, higher extract values and more complex aroma. 12 Regner, F., A. Stadlbauer, and C. Eisenheld. 2001. Molecular Markers for Genotyping Grapevine and for Identifying Clones of Traditional Varieties. Proc. Int. Symp. On Molecular Markers, Eds. Doré, Dosba & Baril, Acta Hort. 546, ISHS 2001.

It is known that both Heunisch and Traminer were important crossing partners throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, and the names of both cultivars have been documented from that time. 13 Sefc K.M., Steinkellner H., Glössl J., Kampfer S. and Regner F. 1998. Reconstruction of a grapevine pedigree by microsatellite analysis, Theor Appl Genet 97: 227-231 (1998). However, despite the theories, the second parent for Riesling had not yet been definitively established by reported DNA findings as of 2018.

Riesling in Europe

Riesling has been cultivated in Europe since medieval times. The names of specific grapevine cultivars began to appear in documentation in the 14th and 15th centuries. Traminer (1349), Gouais ("Golz", 1338) and Riesling (1435) were among the earliest to be mentioned. 14 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 33-41 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016); Sefc K.M., Steinkellner H., Glössl J., Kampfer S. and Regner F. 1998. Reconstruction of a grapevine pedigree by microsatellite analysis, Theor Appl Genet 97: 227-231 (1998).

A likely written reference to the grape cultivar Riesling in Germany was in 1435 in a storage inventory for a castle on the Rhine near Hochheim (in the Rhinegau): twenty-two soliden (currency) for umb seczreben Riesslingen in die wingarten. 15 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007); Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004). The first mention of the cultivar using the more familiar spelling was in 1552 in Hieronymous Bock's Latin Herbal: "Rieslinge grows in the Mosel, Rhine and in the Worms region". 16 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 39-40 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016); Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007); Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004).

Riesling flourished in the Rhine Valley region of Germany in the Middle Ages. The Rheingau is an old cultural region on the Rhine River surrounding Geisenheim and is considered by some to be the traditional home of Riesling. Geisenheim is the home of the famous viticulture institute and winemaking school. The region dates back to pre-Roman times with Celtic settlements.

The first Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne built the Ingelheim Imperial Palace around 807 A.D., across the river from Geisenheim. Legend has it that Charlemagne himself was the first to order that vines be planted on the steep, south facing hill visible across the Rhine from the palace, because he saw that this was where the snow melted first each spring.

That vineyard site across from the Ingelheim palace is the now the famous Schloss Johannisberg, which was the first estate to plant a vineyard exclusively in Riesling and was also the location where the late-harvesting of Riesling grapes to make naturally sweet wine was discovered. For a time, Riesling in California was referred to as Johannisberg Riesling because of this association. 17 Asher, Gerald, The Pleasures of Wine, Selected Essays (Chronicle Books, Ltd., San Francisco, California, 2002); Pigott, Stuart, Riesling (Penguin Books Ltd., London, England, 1991).

From the 16th century, Riesling became recognized as the finest white wine grape in Germany, which then included the Alsace region. It was considered a luxury grape because of its low yield. Riesling was planted in "the best sites for the connoisseurs of the time" (the church and the aristocracy). In successive centuries, church and political figures promoted the grape by ordering that "Rissling" be planted to the exclusion of, or to replace, other varieties. 18 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007); Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004).

The Mosel region was also the home of Riesling from the early times. Trier was an important Roman town in the Mosel region in 286 A.D., where the Romans cultivated Vitis vinifera. The most important church decree specifically related to Riesling came from Clemens Wenzeslaus, Elektor of Trier (Mosel), on May 8, 1787. He ordered the removal of all inferior ("poor") vines to be replanted with "good" grape varieties. Riesling was the only good white grape in the region at the time. 19 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007).

German Riesling achieved great success in the 19th century, when Riesling prices were comparable to the great wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy. It was during that century that Riesling grapes were first imported to California.

Identification of the true Riesling is no longer an issue given DNA technology. The primary European names of the "true Riesling" are Riesling, Riesling weiss or Weisser Riesling. The European name translates into "White Riesling" for the United States. Another complication exists with the use of synonyms, which can be a challenge with European grape cultivars. Of the 120 synonyms listed, the most common in Europe include Rhineriesling (Austria) and Riesling renano (Italy).

The name Riesling became ambiguous in both Europe and the United States when "imposters" and distant relatives of the true cultivar assumed the name. In Europe, some lesser quality cultivars genetically unrelated to Riesling weiss adopted its name - e.g., Riesling Italico (Welschriesling; Walschriesling); Schwarzriesling or Orleans Riesling (Pinot meunier), Laski Rizling. Distant relatives frequently carried the name, sometimes by way of a well-used synonym - Frankenriesling (Sylvaner gruen); Müller-Thurgau (also known as Riesling-Sylvaner). In Australia, Sémillon grapes were used to make Hunter Riesling or Shepherd Riesling.

Identity confusion in the United States

The Riesling grape also suffered from identity confusion in the United States, where unrelated cultivars and distant relatives again adopted the name. Examples included Grey Riesling (Trousseau gris); Missouri Riesling; Hungarian Riesling (Italian Riesling progeny); Emerald Riesling (Muscadelle du Bordelais x Riesling). Often wines made in the "German style" from high acid, light-colored varieties such as Sylvaner and Burger were given the Riesling name even when Riesling grapes were not included in the blend - e.g., Hungarian Riesling, Grey Riesling, Kleinberger Riesling.

The naming confusion was perpetuated by an additional twist when Riesling came to California.

References in California writings from the late 19th century refer to both White Riesling and Johannisberg Riesling. The latter name was a misnomer, as there was no such cultivar abroad. 20 Amerine, M.A. and Winkler, A.J. 1944. Composition and Quality of Musts Wines of California Grapes, Hilgardia vol. 15 (6): 504-550 (1944). The name was apparently adopted "by courtesy after the famous vineyard at Schloss Johannisberg, where [Riesling] predominated". 21 Wetmore, C.A. Part V. Ampelography, “Riesling”, page 3. Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-83 and 1883-84 (1884),Reproduced and Revised from the San Francisco Merchant of January 4 and 11, 1884; TTB (Tobacco, Trade and Tax Bureau), Department of the Treasury. 1999. Extension for Johannisberg Riesling (98R-406P), RIN: 1512-AB 80, Federal Register vol. 64, no. 176 (1999).

Charles Wetmore, Executive Director of the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners in California, explained in 1884: "Custom has, however, attached the name [Riesling] to other varieties, so that when we wish to speak of this genuine variety, we must now use the word Johannisberg to identify it". 22 Wetmore, C.A. Part V. Ampelography, “Riesling”, page 3. Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-83 and 1883-84 (1884), Reproduced and Revised from the San Francisco Merchant of January 4 and 11, 1884. Premium wine producers came to use the words "Johannisberg Riesling" to signify that the wine was made primarily or entirely from the White Riesling from the Mosel or Rhine. 23 Sullivan, Charles L., Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present (2d ed., Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, California, 1994, 2008); Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998).

Riesling vines were planted in the University of California's former Foothill Experiment Station in Jackson, California, in 1889 under the name Johannisberg Riesling. The same cultivar was given the name White Riesling in University vineyards in the first half of the 20th century.

In 1996, the federal TTB (Tobacco, Tax & Trade Bureau) ruled that the name "Riesling" may not be used on wine labels in the case of any grape that is not really a Riesling. The purpose of the TTB regulations was to standardize wine label terminology and reduce consumer confusion by reducing the number of synonyms on wine varieties.

In 1999, the TTB granted an extension for the phase-out of the name Johannisberg Riesling from wine labels until after January, 2006. The name Johannisberg Riesling was "phased out" because it was "not a correct name, [included] a German geographic term and was a specific winegrowing region in Germany". In the course of that regulatory process, wine makers had argued that many "inferior Riesling products had been produced in the 1960's and 1970's and that the name Johannisberg Riesling had been used to distinguish what they believed was their superior Riesling product". They indicated that it would take several years to reeducate American consumers that the term "Riesling" standing alone designated the same wine that was previously known as Johannisberg Riesling. 24 TTB (Tobacco, Trade and Tax Bureau), Department of the Treasury. 1999. Extension for Johannisberg Riesling (98R-406P), RIN: 1512-AB 80, Federal Register vol. 64, no. 176.

Wine writer and historian Charles Sullivan wrote that Riesling had been a confusing term in the history of California wine and that, until 1997 (extended to 2006), it was a term that might go on wine labels as a sort of "generic expression". 25 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). Wine writer Jancis Robinson wrote that the name Riesling was debased in the 1960's and 1970's by being applied to "a wide range of white grape varieties of varied and often doubtful quality". 26 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006).

Only the name Riesling (or the synonym White Riesling) are allowed on wine labels by TTB regulation for the "true Riesling" in the United States in 2018. The names White Riesling (with the notation of synonym names Riesling and Johannisberg Riesling) were still included in the USDA/CDFA California Grape Acreage and Crush Report as of 2017.

Ambiguity related to varietal name and frequent use of synonyms has in the past caused confusion as to the identity of the "true Riesling", particularly in California. The cultivar seems to have attained a clearer definition in 2018. This chapter features only the FPS selections that are "true Riesling" and carry the name Riesling or Riesling renano (the Italian synonym).

Riesling comes to California

German immigrants were primarily responsible for bringing Riesling to California around the middle of the 19th century, at the time that the cultivar was very popular in Europe. 27 Sullivan, Charles, Zinfandel, A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 29-30 (University of California Press, Ltd., Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2003). Some immigrants settled in Santa Clara and Sonoma Counties. By 1856, those two counties had begun to grow in importance for grape acreage planted. 28 Peninou, Ernest P. History of the Sonoma Viticultural District, vol. 1 (Nomis Press, Santa Rosa, California, 1998); Carosso, Vincent P. The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years (1830-1895) (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1951).

California wine makers in the 1850's believed that great wine would probably come from the established European cultivars. German immigrants such as Emil Dresel (Sonoma) and Francis Stock (San Jose) imported white wine varieties such as Riesling, Sylvaner and Traminer. 29 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 27-30 (University of California Press, Ltd., Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2003); Thomas L. Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol. 1, page 263 (University of California Press, 1989).

Stock was probably the first to import Riesling to California to his San Jose nursery prior to 1857. He supplied Riesling cuttings to Dr. George Crane in Napa in 1859; those are believed to be Napa's earliest Riesling. 30 Teiser, Ruth and Catherine Harroun, Winemaking in California (McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York and San Francisco, 1983).

Emil Dresel and Jacob Gundlach planted vineyards that would become Rhine Farm in Sonoma County in 1858. In 1859, Dresel returned to his home in Geisenheim on the Rhine and brought back Riesling cuttings. Agoston Haraszthy secured Riesling cuttings on his trip to Europe in 1861 from the Rheingau region for his Buena Vista vineyard. 31 Sullivan, Charles L., Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present (2d ed., Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, California, 1994, 2008); Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998); Peninou, Ernest P. History of the Sonoma Viticultural District, vol. 1 (Nomis Press, Santa Rosa, California, 1998).

Riesling was one of several German cultivars (along with Sylvaner and Traminer) that helped propel the nascent California wine industry to a measure of fame in the 1870's. 32 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). In the coastal counties of Northern California, the market demanded white wines in the German style. Producers and consumers valued White Riesling (also known as Johannisberg Riesling) for its style and elegance. 33 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 38-39 (University of California Press, Ltd., Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2003) Darrell Corti, a wine merchant in Sacramento, California, describes the elegant German-style Riesling wine as "semi-dry or dry, with low alcohol, refreshing and delicious to taste with good aging ability". 34 Corti, Darrell, Corti Brothers, Sacramento, California, personal interview on September 9, 2009.

In the 19th century, less elegant German-style white wine and blends made from other cultivars were occasionally given the Riesling name or were designated as hock (German style white wines, usually with a large amount of Burger grapes in the blend). 35 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998).

As Riesling is normally considered a cool climate grape, there are only a few regions in California that would appear to support growth of the cultivar at its full potential for high quality wine. Riesling has hard wood, which allows it to be cold hardy and frost resistant for cool wine regions. Additionally, the buds are able to withstand winter's cold temperatures. The bunches are compact and susceptible to botrytis and coulure. The botrytis allows for the production of a range of sweet wines as a result of botrytis dessication. 36 Walker, M. Andrew, Professor, Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, 2009. Personal communication with author on September 24, 2009; Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006).

The variety is adaptable to a wide range of soil types, with highest vigor on fertile soils with high moisture availability. Crop size can range from 4 to 8 tons per acre in California, but Riesling tends to overcrop when grown on deep, fertile soils. 37 Bettiga, Larry J., “Riesling”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, pp. 119-121 (University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3419, 2003) eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert. Darrell Corti explained that Riesling is more sensitive to soil conditions than are other cultivars. There is a slate flavor in Riesling wines grown on slatey soil and a broad or flat taste to wines grown on the loamy soil of the Palatinate in Germany.

One of Riesling's unique viticultural characteristics that allows for diverse wine styles is a long, slow ripening period influenced by warm summers and cold winters. The late-budding cultivar ripens early compared to most cultivars but late relative to other German plantings. The long ripening period allows for a selective harvest for desired ripeness, good flavor and acidity which would decrease over a long ripening period. 38 Walker, M. Andrew, Professor, Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, 2009. Personal communication with author on September 24, 2009; Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006). The result is wines with flavor diversity, from dry to very sweet dessert wines, botrytized specialities and delicate ice wines. 39 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007); Bettiga, Larry J., “Riesling”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, pp. 119-121 (University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3419, 2003) eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert.

A distinctive feature of wine made from this grape is its powerful aroma. Early ripening in warmer regions can cause the wine to lose that aroma and quality and taste dull due to the loss of acidity. 40 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006); Wetmore, C.A. Part V. Ampelography. Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-83 and 1883-84 (1884). The limited supply of cooler climate areas in California inhibited the widespread planting of Riesling in the state until recently.

Wine historian Charles Sullivan wrote that the cooler climate of Sonoma allowed winemakers to approach the German ideal for Riesling more closely than did the Napa climate. He opined that the upper Napa Valley climate was too warm. 41 Sullivan, Charles L., Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present (2d ed., Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, California, 1994, 2008). Eugene Hilgard, head of the then-new Department of Agriculture (Viticulture) at UC Berkeley, spoke at the 1886 Viticultural Convention: "When a Riesling must be rushed through four or five days' fermentation, under the influence of a hot September in the Napa Valley, it is no wonder that its relationship to the produce of Johannisberg is suspected". 42 Sullivan, Charles L., Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present (2d ed., Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, California, 1994, 2008).

In 1884, Charles Wetmore noted that good Riesling was only going to come from vineyards "where over-maturity is difficult to obtain" and where at the time of ordinary ripening the must does not exceed 22% in sugar. 43 Wetmore, C.A. Part V. Ampelography, “Riesling”, page 3. Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-83 and 1883-84 (1884), Reproduced and Revised from the San Francisco Merchant of January 4 and 11, 1884. He wrote that "[Riesling] is an early ripener, otherwise it would not succeed on the Rhine. Experience in Europe shows that it loses its aroma and quality when cultivated in warmer countries and situations where later ripening varieties come to perfection. On the Rhine the greatest perfection is often obtained only when the berries are left on the vines until long after the usual time of vintage". 44 Wetmore, C.A. Part V. Ampelography, “Riesling”, page 3. Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-83 and 1883-84 (1884), Reproduced and Revised from the San Francisco Merchant of January 4 and 11, 1884.

In the 1940's, UC Professors Amerine and Winkler conducted germplasm trials at UC Davis to determine which wines were best suited to California viticultural regions. 45 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials, p. 209, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. In a 1944 publication, the professors grouped the grape districts in the state of California into five climatic regions based on heat accumulation degree days.

Amerine and Winkler recommended White Riesling for high quality dry table wines only in the predominantly coastal counties of regions I and II. They concluded that White Riesling should produce superior wines in region I (Oakville in Napa County; San Benito County; Saratoga in Santa Clara County; Santa Cruz County; and parts of Sonoma County) and fairly good wines in the cooler areas of region II (Monterey County; parts of Napa County; Santa Barbara County; parts of Sonoma County). 46 Amerine, M.A. and Winkler, A.J. Composition and Quality of Musts Wines of California Grapes, Hilgardia vol. 15 (6): 504-550 (1944).

Larry Bettiga, UC Cooperative Extension Viticulture Specialist for Monterey, San Benito and Santa Cruz Counties, cautioned about placement of Monterey and Santa Barbara Counties completely within Winkler region II, stating that those two counties have "some of the coolest growing regions in the state". At the time of the Amerine and Winkler study (1944), those counties were minor grape growing areas and may not have received extensive testing in the study.

Presence in California

Riesling has had an inconsistent track record in terms of acreage planted and wine popularity during the past 150 years in California. In the 1980's, the grape declined in popularity due to a shift in preference to a drier wine style. There was a resurgence in the 21st century.

Frederic Bioletti, of the Department of Viticulture at the University of California, did not place White Riesling on his 1907 list of recommended grapes for California. In 1921, the California acreage figure for Riesling (including Franken, Gray and Johannisberg) was estimated at 2000 acres, out of a total of 22,000 acres of white wine grape acreage. 47 “White Wine Grapes – How They Were Affected by Prohibition”, California Grape Grower, June 1, 1922. In a publication in 1929, Bioletti reviewed the list of principal grapes grown in California at that time and mentioned "Johannisberger [sic.] Riesling" only in passing reference as a blending grape with Franken Riesling (Sylvaner). 48 Bioletti, Frederic T., Elements of Grape Growing in California, California Agricultural Extension Service, Circular 30, March 1929, rev. April 1934.

Prohibition decimated the small California Riesling crop, although Riesling, Cabernet and Zinfandel were the only three varieties named in a category of their own when the State Fair wine competitions resumed in Sacramento in 1934. 49 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel: A History of a Grape and Its Wine, pp. 99-101 (University of California Press, Ltd., Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2003) Department of Agriculture statistics for 1941 to 1945 show no mention of reportable acreage for White or Johannisberg Riesling in California. 50 California Crop and Livestock Reporting Service. December 17, 1945. Preliminary Estimates of California Grape Plantings in 1945, United States Department of Agriculture Bureau and California Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Statistics.

After WWII, wine makers in Germany and the United States began to make sweeter wines, which were increasingly favored by the consumer. California winemakers such as Martini and Wente made the first late-harvest botrytized quality Rieslings in the 1960's. 51 Corti, Darrell, Corti Brothers, Sacramento, California, personal interview on September 9, 2009.

In 1960, only 282 acres of White Riesling were being grown in California. 52 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). Small plantings were begun in the coastal counties between 1968 and 1972. 53 Winkler, A.J. 1964. Varietal Wine Grapes in the Central Coast Counties of California, presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Enologists, Hotel Miramar, Santa Barbara, California, June 26-27, 1964, www.ajevonline.org. Meaningful acreage (1000 to 2000 acres of White Riesling grapevines per county) existed in Sonoma, Napa, Monterey, and Santa Barbara Counties by 1975, with small plantings in Mendocino and San Benito Counties. 54 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). In 1976, White Riesling ranked 4th in acreage (8,552 acres) among all white wine varieties (96,450 total acres) in California, behind French Colombard, Chenin blanc and Chardonnay. 55 Olmo, H.P. 1978. The Role of New Varieties in the Wine Industry, unpublished. (cited as Olmo, 1978 – unpublished).

Young, fruity, slightly sweet White Riesling and Chenin blanc wines gained popularity in the late 1970's. Many less expensive wines were made from high acid, low color grapes from cultivars other than Riesling but were given the Riesling name, e.g., Grey Riesling, Hungarian Riesling. This wine was also made in a light, fragrant, fruity style that was popular with consumers. 56 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998).

The amount of White Riesling acreage in the coastal areas of California began to decrease between 1979 and 1985 in all counties except for Monterey and Santa Barbara. 57 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). At the World Vinifera Conference on Riesling in Seattle in 1989, concern was expressed that in the period 1978 to 1988, vineyards of other major white wine varietals in California tripled, while the area under Reisling vines fell from 8,327 acres to 6,839. 58 Asher, Gerald, “Appreciating Modern Riesling”, San Francisco Chronicle, October 11, 1989.

The Riesling wine boom peaked in the mid to late 1980's, with the simultaneous ascendancy of French style dry white wines such as Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc. The popular preference for dry white wines, along with the perception that Riesling "is a sweet wine", contributed to a smaller footprint for the variety in California. Riesling grape acreage in the state shrank from 11,423 acres in 1983 to 1,850 acres by 2003. 59 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006).

National sales of quality Riesling wines increased significantly around 2006, suggesting a renaissance for quality wine made from that grape, now made primarily in a dry, fruity style. In November 2006, Wine Business Monthly reported in an article entitled "Riesling: The new darling white wine": "[b]etween November 2003 and August 2006, sales of the varietal have grown by 72 percent while case volume has increased 58 percent...Sales of Riesling are so strong that some believe the varietal may eventually challenge Sauvignon blanc's place as the third-largest white varietal sold in food stores." 60 Tinney, Mary-Colleen, “Riesling: The new darling white wine”, Wine Business Monthly, vol. 13 (11): 48-52, November 2006.

A second magazine article in 2008 reported that Riesling consumption in the United States rose 54% between 2006 and 2008. 61 Hall, Lisa Shara, “Riesling on the Rise?”, Wine Business Monthly, October 15, 2008. Another author proposed that Riesling has begun to challenge Chardonnay's dominance because of Riesling's "rich theme and variations". 62 Goldberg, Howard G., “The other white wine”, Wine News, vol. 25 (1): 12 (2008). "Younger drinkers" had begun to show an interest in Riesling wine.

In California, Riesling acreage has doubled since 2003, albeit on a much smaller base than other California white wine grapes. White Riesling acreage in 2017 was 3,849 acres. 63 California Department of Food & Agriculture in cooperation with the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, California Grape Acreage Report, 2017 Crop, April 19, 2018, pp. 5, 9. The Grape Acreage Report shows that Monterey County has by far the most acres [1,535] - followed by Merced County with 846 acres. The Merced County acreage went from 319 acres in 2011 to 849 acres in 2017. Riesling produced in that region of California is used for inexpensive, aromatic white wines which some have characterized as both "delicious and affordable".

States with predominately cooler climates have had success with Riesling plantings. New York State in the Finger Lakes region has a long tradition of quality Riesling production in the United States. Washington State substantially increased its Riesling acreage from 1999 to 2011 (6,320 acres) to become the largest producer of Riesling in the country. 64 Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and José Vouillamoz, WINE GRAPES, p. 891 (HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2012). Oregon and Michigan have also produced notable Riesling wines. 65 Lance Cutler, “Varietal Focus: Riesling”, Wine Business Monthly, page 90, January 2014.

RIESLING SELECTIONS AT FPS

When "true Riesling" vines came to Foundation Plant Services before 2003, they were given the name White Riesling, one of the accepted synonyms for the cultivar. The FPS selections with that variety name were renamed with the simple "Riesling" name in 2003. Riesling was the preferred prime name internationally and was approved by the TTB for wine labels in the United States.

The FPS Riesling collection contains selections that originated in California, Germany, France, Italy, Australia and Argentina.

SELECTIONS FROM CALIFORNIA VINEYARDS

UC Professor Harold Olmo conducted clonal selection of grape cultivars in California in the 1940's and 1950's. His goal was to select variants in vineyards across the state emphasizing good cluster formation, high yields, fruit quality and disease-free status. 66 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials, p. 209, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. Olmo identified White Riesling as an important commercial variety in California in the 1940's; he commented at the time that White Riesling was a premium cultivar known to be "variable and unreliable". 67 Olmo, H.P. 1942 and 1964. A Checklist of Grape Varieties Grown in California, American Journal of Enology and Viticulture vol. 15 (2): 103-105.

Riesling FPS 10 and 28 (Martini)

Olmo began clonal selection work on the Riesling variety around 1950. Riesling 10 and Riesling 28 represent fruits of that effort. The two selections originated from the Martini family's Monte Rosso vineyard in Sonoma County.

The Mt. Pisgah vineyard was originally planted in 1885 on a mountainside in the Mayacamas Range overlooking the Valley of the Moon. Riesling was one of the cultivars planted in the 300-acre vineyard. Phylloxera destroyed the original vines at what became known as Goldstein Ranch. The vineyard was restored and fully producing again by the turn of the 20th century. 68 Peninou, Ernest P. History of the Sonoma Viticultural District, vol. 1 (Nomis Press, Santa Rosa, California, 1998). The vineyard survived Prohibition because the owner at the time sold his grapes commercially and did not make wine. 69 Pitcher, Steve. Monte Rosso – Memoirs of Sonoma’s Grand Cru, Wine News, 2007, www.thewinenews.com/junjul07/cover.asp.

Louis Martini purchased the well-respected Mt. Pisgah vineyard in 1936 and renamed it "Monte Rosso". In an oral history interview with UC in 1973, Martini mentioned that there were quite a few good varieties in the vineyard (including Sémillon, Sylvaner and Folle blanche) when he purchased it, but he did not specifically mention Riesling. Other sources report that Riesling was one of the cultivars on the property. 70 Pitcher, Steve. Monte Rosso – Memoirs of Sonoma’s Grand Cru, Wine News, 2007, www.thewinenews.com/junjul07/cover.asp. Martini himself began planting grapes in the Monte Rosso vineyard in 1939, including what he referred to as Johannisberg Riesling. 71 Martini, Louis M. and Louis P., Wine Making in the Napa Valley, California Wine Industry Oral History Project, University of California, Berkeley (1973); Sullivan, Charles L., Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present (2d ed., Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, California, 1994, 2008).

In 1951, Olmo selected Riesling wood from the Monte Rosso vineyard for clonal evaluation trials. That wood was described as "clones 1-25" from the Monte Rosso vineyard. 72 Olmo, H.P., Undated paper entitled “Early Work on Clonal Selection in California Vineyards”, University of California, Davis, on file at Foundation Plant Services. In the Olmo collection located in the Department of Special Collections at Shields Library, UC Davis, a paper in Olmo's handwriting dated August 1951 states: "Bud selection. L.M. Martini, Monte Rosso. 1-25 White Riesling. Hilltop. Best vines only. Many vines of shot berry type, some flower clusters drying completely and sterile. Some not shedding calyptras". 73 Olmo collection D-280, box 77, folder 10, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

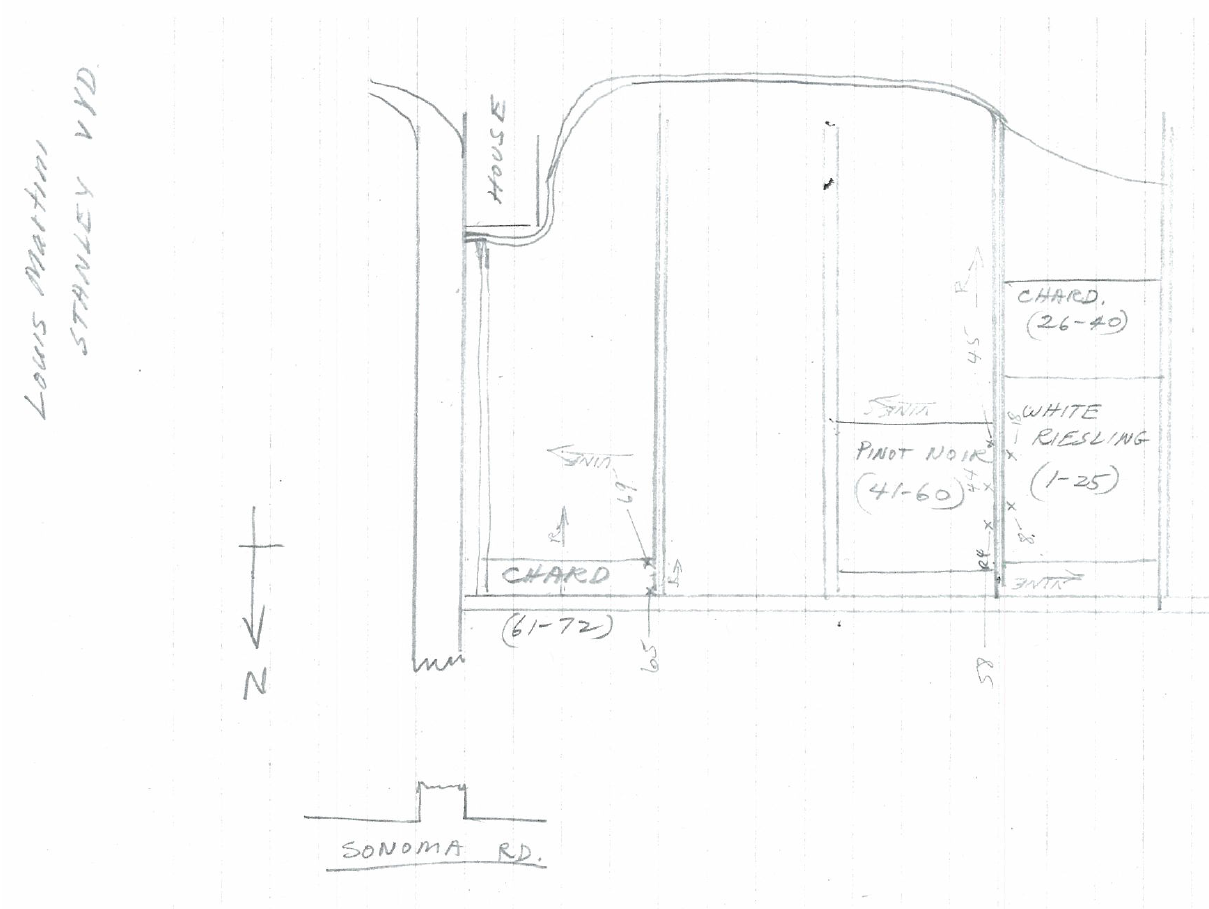

Louis Martini had purchased approximately 200 acres of the Stanly Ranch in the Carneros section of Napa in 1942. 74 Martini, Louis M. and Louis P., Wine Making in the Napa Valley, California Wine Industry Oral History Project, University of California, Berkeley (1973). Olmo conducted "progeny" (clonal) tests on that Stanly Lane property for several varieties, most notably Chardonnay. A handwritten map of the Stanly Lane vineyard property was discovered in the Olmo files in Special Collections. The map indicates that Olmo also conducted progeny tests on the White Riesling Monte Rosso clones 1-25 at the Stanly Lane site. 75 Olmo collection D-280, box 28, folder 39, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

A handwritten document in FPS files (titled "Foundation candidates") dated March 9, 1965, indicates that two clones were brought to FPS from the "Martini vineyard, Napa" - one from location r10 v8 (clone 8) and one possibly clone 25 (r23v3) or clone 18 (above map). 76 Olmo. Paper titled “Foundation candidates”, unpublished paper dated March 9, 1965, on file at Foundation Plant Services. The March 1965 paper is significant because it refers to two Monte Rosso clones coming to FPS from the Stanly Lane vineyard in 1965.

It is clear that Riesling 28 originated from Martini's Monte Rosso vineyard. The FPS database and old [Austin] Goheen indexing records specifically state that the source vine for Riesling 28 was at location r10v8 at the Martini Stanly Lane vineyard, the location of the Monte Rosso clonal trials. The clone arrived at FPS in 1965.

After preliminary index testing, the material from source vine r10v8 underwent heat treatment therapy for 154 days and was planted in the foundation vineyard in May, 1972, as White Riesling 15. White Riesling 15 appeared on the list of registered vines in the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program in 1991.

Although White Riesling 15 never tested positive for virus, the selection underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 1999. The reason for the therapy is unclear, except that the selection was removed from the list of registered vines after virus was discovered in parts of the foundation vineyard in 1992-1993. In 2008, the tissue culture selection created from White Riesling 15 was released as Riesling 28.

The precise origin of Riesling 10 was not as well-documented in the FPS records. Olmo and FPS files strongly suggest that Riesling 10 was the second Monte Rosso clone that was brought to FPS from the Stanly Lane property in Napa at the same time as Monte Rosso "clone 8" (Riesling 28).

FPS source information for Riesling 10 shows that it originated from "a" Martini vineyard around 1965, the same time Riesling 28 came to FPS. Source information for the second clone was entered in the White Riesling section of the Goheen indexing binder as "No number [No no.]", most likely because the exact source vine from Stanly Lane was unclear.

The two Martini Riesling clones received in 1965 were entered together sequentially in the indexing binder and both underwent preliminary index testing at FPS in 1964-65. UCD documents related to clonal trials conducted on the two selections in 1975-1981 state clearly that the source vines for Riesling 10 and 28 were not the same vine at Stanly Lane. 77 Letter from Curtis Alley, FPMS Program Manager, to Mr. and Mrs. Leo Berti, dated November 7, 1975, relative to White Riesling trials; on file at Foundation Plant Services.

The material that became Riesling 10 was initially given the name White Riesling 10 at FPS. Curtis Alley, a UC Davis viticulture specialist and then-Program Manager of FPMS, also referred to Riesling 10 as superclone #107 (a marketing number assigned by Alley to Goheen's heat-treated clones). After preliminary index testing, White Riesling 10 underwent heat treatment for 105 days and was planted in the foundation vineyard in 1967. The selection appeared on the list of registered vines in the R&C Program in 1970. The name was changed to Riesling 10 in 2003.

Riesling FPS 04

Riesling 04 came to FPS before 1963 from an unknown source. The initial entry for the selection in the Goheen indexing binder states "No record of source". Nothing in the historical library documents or other FPS records suggests otherwise. There is no indication in USDA files that the selection was imported from abroad, so it is most likely a local donation. The plant material was originally given the name White Riesling 04 and received no treatment at FPS. The selection first appeared on the list of registered vines in 1971. Its name was changed to Riesling 04 in 2003.

GERMAN CLONES

FPS has numerous Riesling clones from Germany, the presumed home of the cultivar. The clones come from three areas: the Rheingau, the Mosel region and the Pfalz (Palatinate).

Clonal selection in Germany began in the 19th century. 78 Rühl, E.H., H. Konrad, B. Lindner and E. Bleser, Quality Criteria and Targets for Clonal Selection in Grapevine. Proc. 1st IS on Grapevine. Eds. O.A. de Sequeira & J. C. Sequeira, Acta Hort. 652, ISHS 2004. Called "systematic preservation breeding of vine varieties", the process included careful initial individual selection followed by observations and repeated testing on successive clonal descendants. Eventually the method evolved so that the successive A, B and C clone levels were all subjected to progeny testing. Research stations and private breeders adopted the concept of repetitive selection for high performance in the 1920's. 79 Rühl, E.H., H. Konrad, B. Lindner and E. Bleser, Quality Criteria and Targets for Clonal Selection in Grapevine. Proc. 1st IS on Grapevine. Eds. O.A. de Sequeira & J. C. Sequeira, Acta Hort. 652, ISHS 2004; Schöffling, Harold and Stellmach, Günther. Clone Selection of Grape Vine Varieties in Germany, Fruit Varieties Journal 50(4): 235-247 (1996).

By 2003, 99 grapevine cultivars were officially registered at the federal office Bundessortenamt. Seventy-five of those cultivars were bred during the 20th century. The 99 cultivars included 530 registered clones, of which 86 belonged to one cultivar, Riesling. 80 Jung, A. and E. Maul. Preservation of grapevine genetic resources in Germany, based on new findings in old historical vineyards, Bulletin de l’O.I.V. vol. 77: 883-884 (Septembre-Octobre 2004), text presented at the 84th World Congress of O.I.V. in Vienna, July 2004.

The Institute at Geisenheim, Rheingau

The Rheingau region of Germany is thought of as Riesling's historical and traditional home. Some say the Golden Age of Rheingau Riesling was from 1870 to 1930. The region is a small region (forty miles long by three miles wide) and runs along the Rhine River near Wiesbaden. 81 Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004). The International Riesling Foundation reports that many Rheingau Rieslings are made in the dry style and are rich and full-bodied, usually with a pronounced acidity and spiciness to the wines.

In 1872, Prussia established a horticulture and viticulture research institute at Geisenheim (Forschungsanstalt Geisenheim - Geisenheim Research Center) in the heart of what is now the Rhinegau region. 82 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006). The Prussian government also initiated grafting improvement measures and clonal selection activities to improve the health status of grapevines. The institute for grapevine breeding and grafting was later established in 1950 as part of the Geisenheim Research Center. The institute is now known as Geisenheim University. 83 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 70-71 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016); Rühl, Ernst, Director of the Institute for Grape Breeding at Geisenheim, personal communication with author, September 15, 2009.

Clonal selection focusing on White Riesling commenced at Geisenheim in 1921. Selection criteria were based on healthy growth, absence of virus symptoms and performance measures such as consistent yields and high wine quality. One of the goals of the program was to preserve the wide genetic base of the Riesling cultivar. By the end of the 1950's, seven clones were available to growers, including 110 Gm (Geisenheim), 198 Gm and 239 Gm. 84 Bettiga, Larry J., “Riesling”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, pp. 119-121 (University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3419, 2003) eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert; Schmid Joachim, Ries Rudolph, and Rühl Ernst H, “Aims and Achievements of Clonal Selection at Geisenheim”, pp. 70-73, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, Portland Oregon, June 1995. The original clones were tested further and subclones were created and tested, including 239-25Gm.

The virus-tested Geisenheim White Riesling clones and subclones were evaluated from 1978 to 1993, and regular crops with good sugar and acid levels were produced each year. At that time, virus tests were conducted in the institute's laboratories as well as at INRA's Colmar facility. The researchers concluded that no significant differences could be detected between them in regard to yield, sugar, acid levels and pH, and attributed that result to a generally high selection level. 85 Schmid Joachim, Ries Rudolph, and Rühl Ernst H, “Aims and Achievements of Clonal Selection at Geisenheim,” pp. 70-73, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, Portland, Oregon, June 1995.

There are three Geisenheim Riesling clones in the FPS public collection: two selections of Geisenheim 110 (110 Gm), one selection of Geisenheim 198 (198 Gm) and one selection of Geisenheim subclone 239-25 (239-25Gm).

Clone 110 Gm

German clone 110 Gm is represented in the FPS collection by Riesling 09 and Riesling 24. This clone has an extremely fruity, slightly muscat flavor, and in warmer sites it is regarded as not typical of German Riesling wines. 86 Bettiga, Larry J., “Riesling”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, pp. 119-121 (University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3419, 2003) eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert.

Riesling 09 was imported to Davis from Geisenheim in 1952 with the notation that it was "Rhein Riesling klon 110" (USDA Plant Introduction #200886). The selection underwent heat treatment for 112 days as White Riesling 03. FPMS Manager Curtis Alley assigned it the alternate designation of superclone #106. After the heat treatment, the selection was renumbered White Riesling 09 due to the policy of FPMS at the time to assign a new selection number to material which has undergone treatment. White Riesling 09 was first planted in the foundation vineyard in 1965 and appeared on the list of registered vines in 1967. The name was changed to Riesling 09 in 2003.

Riesling 24 was also imported to Davis from Geisenheim in 1952 as "Rhein Riesling klon 110". It has the same source as Riesling 09 and was originally distributed by FPS as White Riesling 03. The original material for this selection tested positive for Rupestris stem pitting virus and was dropped from the California R&C Program in the early 1980's. At that time, vines testing positive for RSP virus were not allowed in the Program. The plant material was maintained at FPMS and the name was changed in 2003 to Riesling 03. In 2007, microshoot tip tissue culture therapy was used to create an RSP-free selection of 110 Gm, which was thereafter given the name Riesling 24.

Clone 198 Gm

German clone 198 Gm is represented in the FPS collection by Riesling 17. Clone 198 Gm has lower crop yields with wines of elegant fruitfulness and pronounced flavor, but with all components in good balance. 87 Bettiga, Larry J., “Riesling”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, pp. 119-121 (University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3419, 2003) eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert. Clone 198 Gm is ideal for the production of high quality, semi-dry wines. Geisenheim clones 198 Gm and subclones of 239 Gm are recommended for planting in warmer sites. 88 Schmid Joachim, Ries Rudolph, and Rühl Ernst H, “Aims and Achievements of Clonal Selection at Geisenheim,” pp. 70-73, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, Portland, Oregon, June 1995.

Riesling 17 was imported to Davis from Geisenheim in 1952 under the name "Rhein Riesling klon 198" (USDA Plant Identification #200888). The selection was named White Riesling 02 and did not undergo any treatment at FPS. It was first planted in the foundation vineyard in 1961 and appeared on the list of registered vines in 1965. The name and number were changed to Riesling 17 in 2003. The selection number was changed to 17 because FPS already had a selection named Riesling 02.

Sub-clone 239-25 Gm

German clone 239-25 Gm is represented in the FPS collection by a sub-clone which FPS has given the name Riesling 23. This versatile clone with its sub-clones is the most widely distributed selection in Germany and produces fruity wines with a wide range of terpenes, resulting in a spectrum of fruitfulness. 89 Bettiga, Larry J., “Riesling”, Wine Grape Varieties in California, pp. 119-121 (University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3419, 2003) eds. L. Peter Christensen, Nick K. Dokoozlian, M. Andrew Walker, and James A. Wolpert; Schmid Joachim, Ries Rudolph, and Rühl Ernst H, “Aims and Achievements of Clonal Selection at Geisenheim,” pp. 70-73, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, Portland, Oregon, June 1995.

In the mid-1980's the Oregon Winegrowers' Association and Oregon State University (OSU) collaborated on a project related to a mutual interest in European clonal material. They imported many European clones to Oregon. In response to interest from the California grape and wine industry, OSU agreed in 1987-88 to make some of the clones available for the public collection at FPS.

Riesling 23 was imported from Geisenheim by OSU and then forwarded to FPMS in 1987. OSU received the original Riesling subclone material labelled "Riesling 239-25 Gm". When the selection first arrived at FPS, it was assigned the name Riesling S1. Tests at FPMS in the late 1980's detected RSP virus, so the selection was distributed in the 1990's as "non-registered, RSP+ Riesling 02". [This selection should not be confused with White Riesling FPS 02, which was the precursor to Riesling 17, see above].

This selection was eventually renamed from Riesling 02 to Riesling 23. Riesling 23 was created by vegetative propagation techniques where a cutting was taken from the original source plant (Riesling 02) and advanced to Riesling 23 in 2007. There is no indication in either the FPS database or the FPS tissue culture records that this selection ever underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy prior to 2007, although an article in the 2007 FPS Grape Program Newsletter so indicated. It appears that the article was in error. New selection number "23" was most likely a product of moving the selection from the Department of Viticulture & Enology vineyard location into the FPS foundation vineyard.

Riesling 23 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2010 and has qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard.

Proprietary Geisenheim selections

2006

There are three proprietary German subclones in the grapevine collection at FPS that initially came to FPS in 2006 at the request of a former nursery, Vino Ultima, Inc. The subclones are proprietary to Geisenheim University, which now controls the subclones at FPS. Geisenheim University entered into a contract with licensee Duarte Nursery in Hughson, California, in 2014 to distribute proprietary Geisenheim clones in the United States.

Riesling FPS 25, 26, and 27 represent subclones of clone groups 110, 198, and 239 from the Geisenheim mother blocks. The subclones are: 110-14 Gm (Riesling 25); 198-44 Gm (Riesling 26) and 239-34 Gm (Riesling 27).

In the 1960's, the clonal development program at Geisenheim was directed by Helmet Becker, who chose to develop subclones. The subclone process involved "reselecting" from the old mother vines to develop separate subclone lines within a single clone group. For example, FPS received subclone 239-25 Gm (Riesling FPS 23) through OSU in the Winegrowers Program in 1987. That subclone was the progeny of one vine in the "clone group 239" mother block. In 2006, FPS received a second subclone from the clone group 239 mother block, i.e., subclone 239-34 (Riesling FPS 27). The second subclone was separately developed from a different vine in the 239 mother block.

Ernst Rühl, Director of the Institute for Grape Breeding at Geisenheim, indicated to wine author John Haeger that the identification of subclones was intended as an insurance policy; if propagations from one subclone within the clone group were found to have virus, progeny from the other subclones would not be impacted. 90 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, p. 72 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016).

2014

Three additional proprietary Riesling clones were imported to Foundation Plant Services from Geisenheim University in 2014.

Geisenheim subclone 64-177-3 Gm qualified for the FPS Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2016 as Riesling FPS 31 and for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2017. Riesling clone 64 Gm was released in Germany in the 1950's. Clone 64 reportedly exhibits "showier" aromatics than some of the other clones and produces relatively light flavors and good balance. 91 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, p. 72 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016).

A second subclone from Geisenheim in 2014 became Riesling FPS 32. In 2004, Geisenheim University took over a nearby clonal selection program from the Hessian State Domaine at Erbach. One of the best known of the source vineyards for the Erbach vineyard is Steinberg, once cultivated by Cistercian monks. Steinberg clone 7 Gm came to FPS in the form of subclone Steinberg 7-5-9 Gm. The material has been assigned the name Riesling FPS 32. The clone has also qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard.

Red Riesling

This unusual proprietary clone came to Foundation Plant Services in 2015 from Geisenheim University. The material is a red Riesling clone (Roter Riesling or Riesling Rot), which is a color mutation of white Riesling with dark pink berries. The clone has red pigmented grape berry skins. The thicker skins have phenolics different from white Riesling. The variety may have botrytis resistance. The plant material at FPS is Geisenheim clone 26.

The original Geisenheim material successfully completed testing to qualify for the FPS Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2017 as Riesling FPS 33. The original material also underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS and qualified for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2017.

The Mosel region

The Mosel is portrayed as the quality region for Riesling wine. Traditionally the wines tended to be delicate, lower in alcohol (often 8%), higher in acid, floral and intensely mineral. According to the IRF, the wine is usually made in an off-dry style because of the higher acidity. At the same time, this region has produced excellent botrytized wines because of the long-ripening period allowed by the sheltered river valleys and a favored moist climate to promote botrytis. 92 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007); Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004). Steep south facing vineyards allow that variety to flourish in this northern area.

The Central Office for Clonal Selection is located in the cities of Trier and Bernkastel-Kues, Germany, in the Mosel region. Dr. Günther Stellmach is associated with that office and, in 1987, was responsible for sending what was then called the "Riesling 21B" clone to the grape program at Oregon State University (OSU). 93 Robert B. Ball and Susan Nelson-Kluk, Final Report on Projects Funded by Winegrowers of California, page B-8, July 29, 1988. The selection was in turn sent from OSU to FPMS as part of the Winegrowers' Project.

German clone 21B was found in the Mosel region in Bernkastel-Kues (the B in the name allegedly refers to Bernkastel). Private breeder Nicolaus Weis of Weis Reben in Leiwen selected budwood from his family's vineyard beginning around 1947. The Weis family had obtained their plant material from the Bullay Institute, a major center for vine breeding before World War II. The clone selected by Weis became known as Weis 21 or Weis 21B. 94 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, p. 73 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016)

When the berries of Weis 21 are smaller, the must density and wine quality increase. 95 Schöffling, Harold and Stellmach, Günther, Clone Selection of Grape Vine Varieties in Germany, Fruit Varieties Journal 50(4): 235-247 (1996). A common comment from growers is that the clone is highly productive

The Riesling 21B clone was initially given the name Riesling 21B S1 at FPS. Sometime prior to 2000, the name was changed to Riesling 01.

The Pfalz (Palatinate)

The Pfalz region in the Palatinate joined the Rheingau and Mosel as a great wine region in the middle of the 19th century. The "southern wine route" (Südliche Weinstrasse) runs from Neustadt to the French border along the Haardt Mountains. 96 Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004). The climate in the region is benign, and Riesling accounts for 20% of the vineyard plantings. 97 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006).

Pfalz Riesling typically ripens to over 12 % alcohol and appears to be particularly suitable for vinification to "completely dry, relatively corpulent" Rieslings. Another description of Pfalz Riesling describes them as "clear, pure wines". The region is also known for its spicy Spätlesen and Auslesen. 98 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006). That spicy character is attributed to one of the German Riesling clones, clone 90, which is unique to the Pfalz.

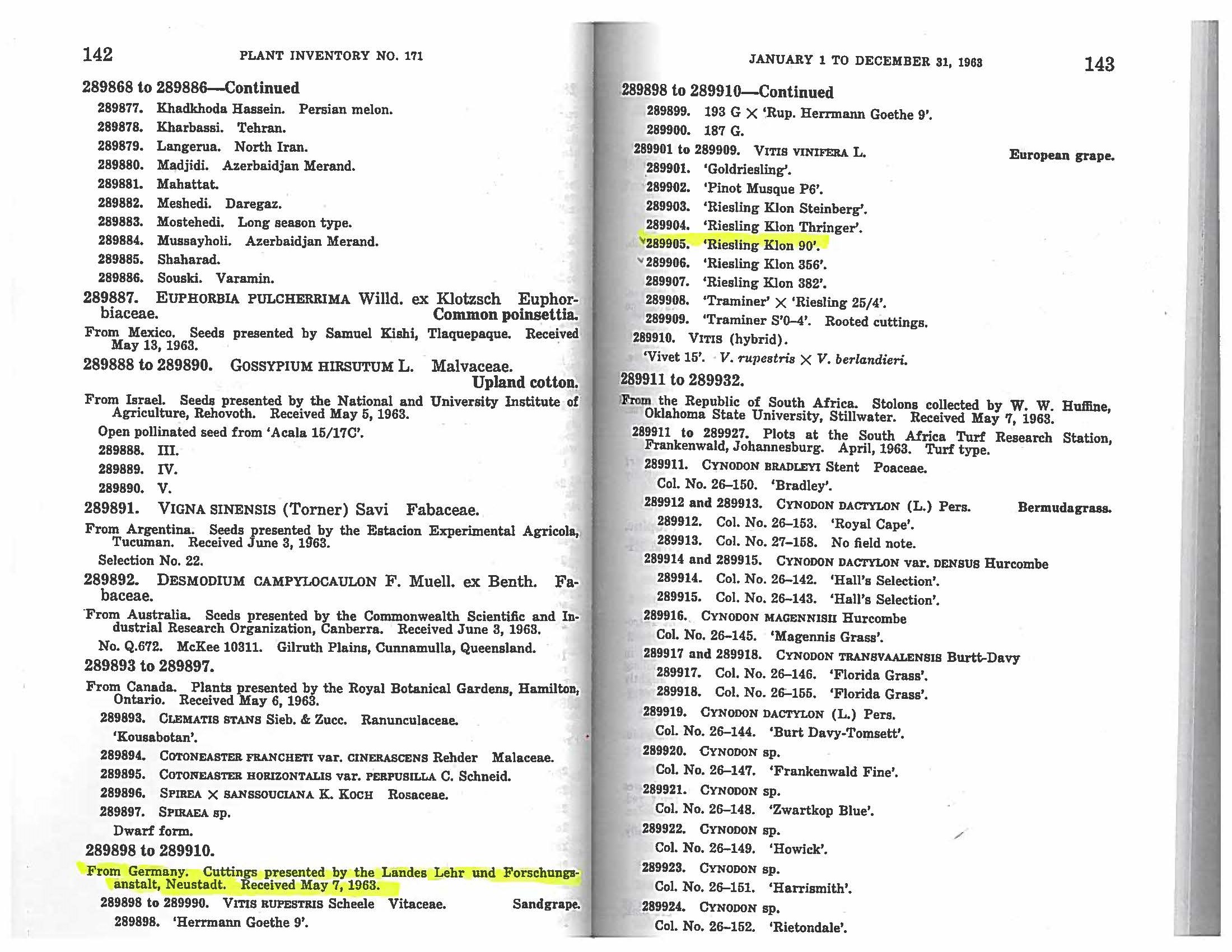

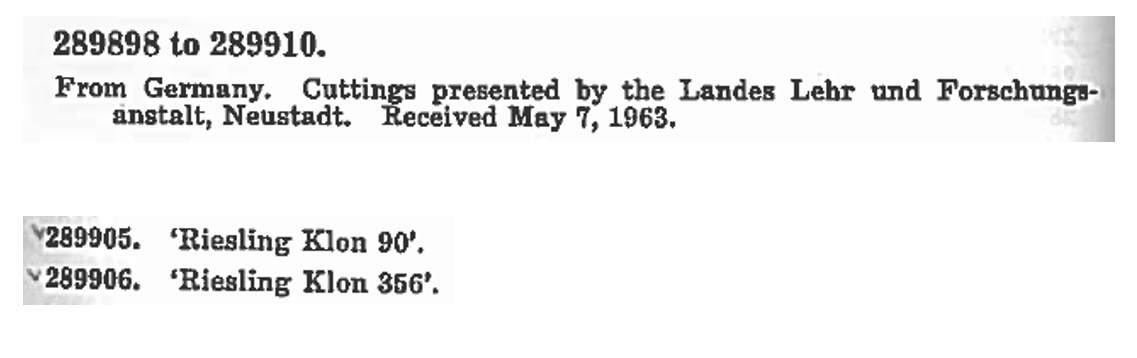

Neustadt in the Pfalz region is an important center for viticulture and wine research. Clonal development work is done at the Neustadt Research Institute, which is now known as Dienstleistungszentrum Ländlicher Raum Rheinfalz (known in 1963 as Landes Lehr und Forschungsanstalt at Neustadt). The wine school in Neustadt was established in 1899 by the citizens of Neustadt an der Weinstrasse. The Hessian wine academy at Oppenheim dates from 1885. 99 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, pp. 577-579 (3rd ed., Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2006).

Two German clones from the Pfalz region are included in the FPS public collection: Riesling FPS 12 and Riesling FPS 21. Both were sent to Davis in May, 1963, from the Neustadt Research Institute.

Clone N 90 [Neustadt]

Riesling FPS 12 is German clone 90 (also known as N 90, for "Neustadt 90"). Clone 90 was first recognized as a superior clone by German researchers in 1913. Reportedly, years of experimentation proved the clone to be aromatic, cold tolerant and disease resistant. 100 Lynn Alley, “Send in the Clones”, Wine Spectator, November 13, 2008, www.winespectator.com.

This selection arrived in Davis in 1963 from the Landes Lehr und Forschungsanstalt, Neustadt with the label "Riesling Klon 90". Federal importation records in the United States showed that "Riesling Klon 90" was assigned USDA Plant Identification no. 289905 at that time. (see below). The Institute at Neustadt cannot confirm the 1963 shipment because it has apparently lost its records of that shipment.

The clone N 90 material received no treatment at FPS and was planted in the foundation vineyard in 1969 as White Riesling 12. White Riesling 12 first appeared on the list of registered vines in the California R&C Program in 1970. The name of this selection was changed to Riesling FPS 12 in 2003.

In 2014, wine writer John Haeger researched the clones in Germany for his book, Riesling Rediscovered, Bold, Bright and Dry (2016). He discovered that the earliest systematic clonal selection program for Riesling in Germany began at Neustadt in 1910. A royal wine and pomology institution (now known as DLR Rheinpfalz) studied the most fruitful vines in Pfalz vineyards and selected the best 15 for clonal trials. Over time, one clone "excelled above all others and was designated N 90". The clone reportedly had a special floral character. Following additional clonal development work after World War II, Clone N 90 was registered with the Bundessortenamt in 1956. 101 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 70-71 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016)

Haeger went on to report that, in the 1990's, the Institute at Neustadt reselected from its N 90 mother block looking for possible significant mutations in the 40 years since N 90 was first registered. Haeger was told that the "third generation selections showed no substantially deviating characteristics". None of the "re-selections" was separately registered with the Bundessortenamt. Clone N 90 remains as it was in 1956 and is the only Riesling clone to originate at Neustadt. 102 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 70-71 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016)

In 2008, clone N 90 was again imported from Germany, this time to New York State by special arrangement with the USDA/APHIS. An approved quarantine block was planted at a vineyard owned by Dr. Konstantin Frank Vinifera Wine Cellars overlooking Keuka Lake in the Finger Lakes region. The clone N 90 scions were grafted on Neustadt SO4 rootstock. The block was monitored by Dr. Marc Fuchs of Cornell University. Experimental wines were made. Dr. Frank has indicated a preference for the wines made from the clone N 90 material imported in 2008 over the clone N 90 material received at FPS in 1963. 103 John Winthrop Haeger, RIESLING REDISCOVERED, Bold, Bright and Dry, pp. 70-71 (University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2016)

Trautwein 356/356Fin

The second selection imported to the United States from the Institute at Neustadt in 1963 was Riesling FPS 21. The source of that selection appears on the USDA paperwork as "Riesling clone 356".

Riesling clone 356 was originally called Trautwein 356, indicating selection by a man named Trautwein. When he died, a man named Finkenauer continued selecting the A clones. Finkenauer maintained the number 356 but changed the clonal designation to 356Fin.

According to Matthias Zink, manager of the vine nursery at Neustadt, clone "356 Fin" was previously held at the Institute at Bad Kreuznach; it is now held at the Institute in Oppenheim (Dienstleistungszentrum Ländlicher Raum Rheinpfalz Rheinhessen-Nahe-Hunsrück). FPMS Program Manager Curtis Alley reported that the clone sent to FPS was the iteration of clone 356 that was held at Bad Kreuznach. 104 Curtis Alley, “An update on clone research in California”, pp. 31-32, Wines and Vines, April 1977.

Upon its arrival in Davis, clone 356 was given the name White Riesling 14 and was planted in the FPS foundation block in 1970. It does not appear on any of the lists of registered selections in the 1970's and 1980's, even though all of the original virus tests were negative. In 1981, White Riesling 14 tested positive for RSP virus, which would have disqualified it for the California R&C Program at that time. The name was changed to Riesling 14 in 2003.

In 2006, Riesling 21 was created from Riesling 14 by use of microshoot tip tissue culture therapy

FRENCH CLONES

The French region of Alsace, near the German border, claims to be one of the locations where Riesling was born. 105 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007); Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004). From the 16th century, Riesling became recognized as the finest white grape in Germany, which at the time included Alsace.

A possible early written reference to the cultivar appeared on a 1348 map in Kintzheim, Alsace, as "zu dem Russelinge". 106 Price, Freddy, Riesling Renaisssance (Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. London, 2004). The spelling was similar to several cultivars of the time, so no definitive conclusion can be drawn. The name "Riesling" was mentioned in writing for the first time during a 1477 visit by Duke René of Lorraine. 107 Fischer, Christina and Ingo Swoboda, Riesling (Werkstatt München, Buchproduktion, Munich, 2007).

Clonal selection work on Riesling was done in France at INRA's Colmar Center in Alsace beginning in the 1950's. One commercially successful clone was developed in that program. Prior to the certification, the clone was known locally as INRA-CV 813. The ENTAV-INRA catalogue shows that clone 813 was certified in 1971 and the clone number was changed to CTPS 49. The clonal material was planted at Bergheim at the Espiguette Estate. 108 ENTAV- INRA-ENSAM- ONIVINS, Catalogue of Selected Wine Grape Varieties and Certified Clones Cultivated in France, page 245 (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, CTPS, 1995).

There are three Riesling selections from France in the FPS foundation grapevine collection - Riesling FPS 29, Riesling FPS 20 and Riesling ENTAV-INRA® 49. All three are versions of same French clone.

Riesling 29

The plant material that became Riesling FPS 29 came to Foundation Plant Services via Oregon State University as part of the Winegrowers' Project in 1987. The Winegrowers' Report indicates that "White Riesling clone 813" (certified in 1971) was imported from the French government research center in Colmar, the Centre de recherché de Colmar of the Institut national de la recherché agronomique (INRA). The material for this selection is reported to be White Riesling clone 813 from Colmar, Alsace.

The plant material remained in a quarantine vineyard at FPS for years under the name White Riesling S1. The original material underwent disease testing at FPS and successfully qualified for the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2010. The name of the selection was changed to Riesling 29.

Riesling 20

Riesling FPS 20 was donated to the FPS public grapevine collection in 1999 by Clos Pepe Vineyards in Lompoc, California. The selection is a Riesling clone reportedly from Alsace, France, most likely Alsatian clone 813. The original material tested positive for leafroll virus, so it underwent microshoot tip tissue culture virus elimination therapy in 2005. Riesling 20 qualified for the FPS Classic Foundation vineyard in 2008.

Riesling ENTAV-INRA® 49

The Etablissement National Technique pour l'Amelioration de la Viticulture (ENTAV) is an official agency certified by the French Ministry of Agriculture and responsible for the distribution of trademarked French clonal material. The ENTAV-INRA® authorized clone trademark identifies protected French clonal materials internationally. Trademarked importations come directly from official French source vines.

Riesling ENTAV-INRA® 49 is the official French clone for Riesling 49 and came to FPS in 2000. The ENTAV-INRA literature on the clone indicates that, when yields are controlled, the wines are very well balanced and very typical. Riesling ENTAV-INRA® 49 is a proprietary selection at FPS and is available from ENTAV licensees.

ITALIAN CLONES

Riesling was introduced to Italy in the 19th century, probably from the Rhine Valley in Germany. 109 Calò Antonio, Scienza Attilio, Costacurta Angelo, Vitigni d’Italia, p.660-661 (Edagricole – Edizioni Agricole della Calderini s.r.l., 2001) (in Italian). The best locations for planting in Italy are Trentino Alto Adige, the area above Lago di Garda in the Italian Alps and in Friuli near Slovenia. Riesling is known in Italy by the synonym name of Riesling renano.

There is another grape cultivar in Italy with the name "Riesling". That cultivar is genetically unrelated to the "true Riesling" (Riesling renano) but is named Riesling Italico (also known as Walsch or Welsch Riesling). Riesling Italico has characteristically different morphology and produces distinctly different wine than Riesling renano. 110 Calò Antonio, Scienza Attilio, Costacurta Angelo, Vitigni d’Italia, p.662-663 (Edagricole – Edizioni Agricole della Calderini s.r.l., 2001) (in Italian).

There are three Riesling clones from Italy in the FPS grapevine collection - Riesling FPS 19, Riesling FPS 34 and Riesling renano FPS 01.

Riesling 19

The plant material that eventually became Riesling FPS 19 was imported directly to FPS from Italy in 1988 as a follow up to the Oregon Winegrowers' Project. The selection came to FPS from Dr. Antonio Calò of the Instituto Sperimentale per la Viticoltura (ISV) in Conegliano, Italy, and was labeled Riesling Italico clone ISV-CPF 100. 111 Robert B. Ball and Susan Nelson-Kluk, Final Report on Projects Funded by Winegrowers of California, July 29, 1988. "CPF" stands for "Centro Potenziamento Friuli" (Improvement Center for Friuli), but there is no Riesling clone (either renano or Italico) in Italy with the number 100.

Once at FPS, the selection was originally assigned the name Riesling Italico S1. A new selection was created from Riesling Italico S1 in 2001 using microshoot tip tissue culture therapy, resulting in Riesling Italico 03.

Subsequent ampellographic and DNA analysis (2003) at FPS revealed that the FPS 03 plant material was not Riesling Italico but was, in fact, the true Riesling. The name was changed to Riesling FPS 19 in 2005 to reflect its correct cultivar identification. Riesling FPS 19 first appeared on the list of registered vines for the R&C Program in 2005.

Riesling 34

The second true Riesling from Italy in the public grapevine collection at FPS is Riesling FPS 34. The selection was imported directly to FPS in 1988 as part of the Winegrowers' Project. The plant material was supplied by Dr. Antonio Calò of the Istituto Sperimentale per la Viticoltura in Conegliano. The material is reportedly ISV clone 10. It is possible that the uncertain clonal reference for Riesling 19 (above) could also be ISV 10, rather than the nonexistent ISV 100.

While in the quarantine vineyard and undergoing disease testing at FPS, this selection was known as Riesling S2. The selection underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy at FPS in 2007 and was advanced to a new selection name, Riesling 30, in 2013; the new selection remained on hold for repeat disease testing. The material underwent a second round of microshoot tip tissue culture therapy in 2017 and was assigned the selection number Riesling 34.

Riesling 34 continues to undergo testing at FPS as of 2018.

Riesling renano 01

This proprietary selection came to FPS in 1998 from Vivai Cooperativi Rauscedo (VCR) in Italy. It is VCR clone 3. VCR 3 reportedly has small clusters and average and uniform berries, with good resistance to botrytis bunch rot. 112 Calò Antonio, Scienza Attilio, Costacurta Angelo, Vitigni d’Italia, p.660-661 (Edagricole – Edizioni Agricole della Calderini s.r.l., 2001) (in Italian). The selection underwent microshoot tip tissue culture disease elimination therapy in 2003.

Riesling renano FPS 01 is distributed by Rauscedo licensees in the United States. Rauscedo has chosen to retain the name Riesling renano for this selection.

CLONES FROM THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE

Riesling 16 (Australia)